The Crawl

My brother was offended I would attend my colleague’s stag-do and not his own; I reassured him it was nothing personal, that this stag-do was just down the road and if I didn’t like it then I could walk home. Truthfully I held no strong affection for this particular colleague; there were moments when I imagined I could, but most of our time together had me questioning the six years between us.

Instead I met a few friends down the diner, where we ate large breakfasts with coffee & beer, then walked down to the next pub on the crawl. The rest of them arrived as a loud group, a fanfare, talking of a fight they almost had with a homeless man outside Liverpool St station. Already there were rules in place, numerous rules to complicate & excite things; none of which I cared for, so that, when the occasion came, I looked at them, sipped my beer, wondering how the day would go. We walked along in staggered partnerships. It was a grey day. Rain fell; not enough to dash through, too much to stay dry in. The stag was dressed in a rival team’s football shirt. As we walked from one pub to another, the countrymen — excited by the city & booze — hollered at women and were terrible; a large group of men, pissed and predictable, disgusting, a whimper of bravado & in relationships they thought they were better than. I heard one man shout to a group of women—‘You can shit on my chest!’

Another— ‘Didn’t you just get engaged?… Congratulations!’

Everyone laughed.

‘This pub we going to, does it have music?’ he asked.

I turned around and put on a country accent to mock him— ‘“Does it have music? Does it have a working toilet?” Course it fuckin’ does, you prat …Hate these country fucks.’

Instead I met a few friends down the diner, where we ate large breakfasts with coffee & beer, then walked down to the next pub on the crawl. The rest of them arrived as a loud group, a fanfare, talking of a fight they almost had with a homeless man outside Liverpool St station. Already there were rules in place, numerous rules to complicate & excite things; none of which I cared for, so that, when the occasion came, I looked at them, sipped my beer, wondering how the day would go. We walked along in staggered partnerships. It was a grey day. Rain fell; not enough to dash through, too much to stay dry in. The stag was dressed in a rival team’s football shirt. As we walked from one pub to another, the countrymen — excited by the city & booze — hollered at women and were terrible; a large group of men, pissed and predictable, disgusting, a whimper of bravado & in relationships they thought they were better than. I heard one man shout to a group of women—‘You can shit on my chest!’

Another— ‘Didn’t you just get engaged?… Congratulations!’

Everyone laughed.

‘This pub we going to, does it have music?’ he asked.

I turned around and put on a country accent to mock him— ‘“Does it have music? Does it have a working toilet?” Course it fuckin’ does, you prat …Hate these country fucks.’

My mate and I would run ahead of the group and dash between closing tube doors to get the circle line before them, sparing ourselves the shame of laddishness, and we passed all along in silence. We walked the embankment. Had London ever been so quiet? It silently glistened in falling grey, unrelenting, cold & bitter the wind from the channel. We ordered a round and enjoyed a few moments of solitude. Chips steamed; dressed in gold, they tasted so good. Somehow I became navigator — it was a role I revelled in, quite frankly, and I did so well until I took us on a walk to the wrong (south) end of St James (north). We walked through the rain and dodged puddles; the mammoth park hidden in dark. Drunks slapped French umbrellas. I apologised when I realised I had taken them the wrong way; they all threw their hands up at me. I’m not so good with west London. I liked how quiet things were, I liked the storm and the warmth that came with frosted glass & varnished wood; it reminded me of christmas when I would walk through the cold with my family and finally happen upon an open fire or enthusiastic central heating system. Still I kept my distance, befriended not a soul, but observed, like Attenborough in the fifties. If one should make eye contact I would hold it until they walked away.

![]()

Again my friend and I caught the tube (St James) before them (westbound) and ended up alone because they avoided a venue. So he and I walked to a cafe where the jobsworthy chased us out the toilet, then found a place to drink shit beer and recover ourselves. Down Marylebone the puddles flickered a pulse of pace & sputtering cars. We caught them up in a bar that reminded me of an ex (where I first met her sister). It was all illuminated in neon lights & barmaids who hated every ounce of our being. One of our group pulled out his cock (for the second time) and began to piss on the bar. No one noticed, so he got away with it and the pool around his cheap suede shoes got deeper.

It was happening: for hours men had been falling away, like crabs in the tide.

Two days later, to my mother: ‘It became like university … I thought it’d be fun, but it wasn’t, it was awful, and then it just became a test of endurance, so that I could say I could I got through it.’

The conversations bored me. I talked to them about their bad relationships and their mortgages and all the sorrow I had always imagined they had wrapped up in their lives. My mate and I got on the same tube (after some difficulty, which involved them all fighting each other in the tunnels of Baker St, tumbling, clowns) but sat far away. The rest of them got into a fight with a beggar who walked down the carriages with an empty coffee cup.

They alighted a stop early and we met them in the final pub.

This was where it all ended. I was so glad to have made it. A small part of me — pink, wet and tender — was happy to have a steine and wash everything off. In there it was truly the end.

It was happening: for hours men had been falling away, like crabs in the tide.

Two days later, to my mother: ‘It became like university … I thought it’d be fun, but it wasn’t, it was awful, and then it just became a test of endurance, so that I could say I could I got through it.’

The conversations bored me. I talked to them about their bad relationships and their mortgages and all the sorrow I had always imagined they had wrapped up in their lives. My mate and I got on the same tube (after some difficulty, which involved them all fighting each other in the tunnels of Baker St, tumbling, clowns) but sat far away. The rest of them got into a fight with a beggar who walked down the carriages with an empty coffee cup.

They alighted a stop early and we met them in the final pub.

This was where it all ended. I was so glad to have made it. A small part of me — pink, wet and tender — was happy to have a steine and wash everything off. In there it was truly the end.

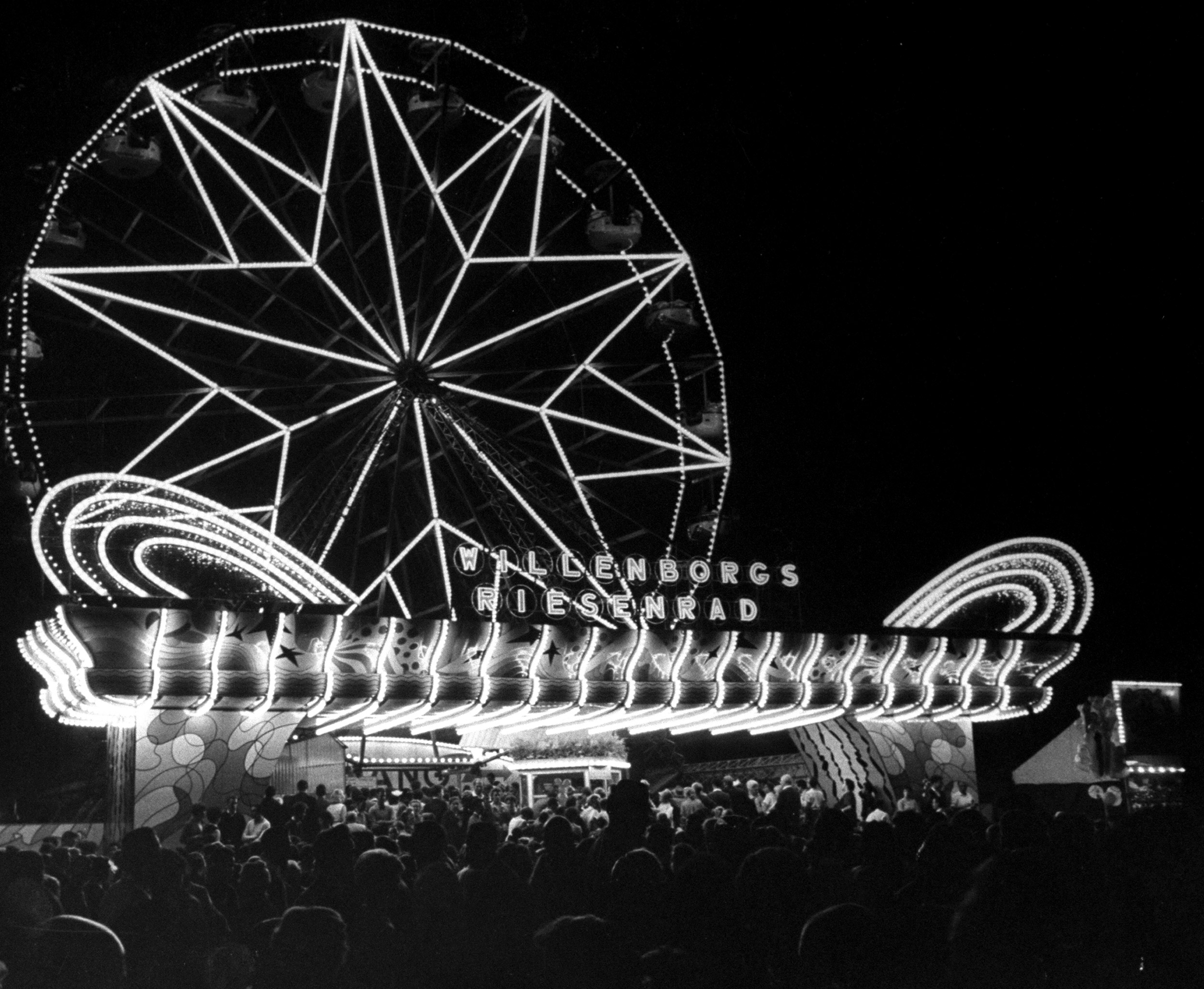

A German oom-pah band came out to soundtrack the disastrous pissed as they stood on stools, banged the ceiling, and shouted dumbly. My mate necked his steine; satisfied he’d filled the brief and made off for south London. I went outside. A woman approached me and began to talk. She was German. ‘What the hell are you doing here?’ I asked, and she told me she got a staff discount, even though she had quit some months ago. ‘Well, good luck with that,’ I said, and went back inside.

![]()

Things were getting destroyed. Members of the arrangement were falling over. It was each man for himself as they all, in a drunken fervour, tried to pull whoever they could. The women resisted as much as they could, but did not move away. I observed, like Attenborough in the fiftites. One of the women came up to me—‘What’s the matter with you?’ I told her there was nothing wrong with me, as everyone danced to this song from the early eighties. She looked at me suspiciously. I suspected that one day she might do better than this, but not as well as she could. A colleague arose, wrapped his arm around her neck and started — with half-shut eyes — to nuzzle her throat. So what if I scorned all around, I wanted to drink! I was over twelve hours in and wanted more drink! I was alone now, a bit dazed, exhausted from many things but the London weather banging at the door was not one of them.

The bar cleared at just gone twelve. I’d made it through. I watched people stumbling down the stairs into the capital’s cold. I’d made it. Where was the cab?

Things were getting destroyed. Members of the arrangement were falling over. It was each man for himself as they all, in a drunken fervour, tried to pull whoever they could. The women resisted as much as they could, but did not move away. I observed, like Attenborough in the fiftites. One of the women came up to me—‘What’s the matter with you?’ I told her there was nothing wrong with me, as everyone danced to this song from the early eighties. She looked at me suspiciously. I suspected that one day she might do better than this, but not as well as she could. A colleague arose, wrapped his arm around her neck and started — with half-shut eyes — to nuzzle her throat. So what if I scorned all around, I wanted to drink! I was over twelve hours in and wanted more drink! I was alone now, a bit dazed, exhausted from many things but the London weather banging at the door was not one of them.

The bar cleared at just gone twelve. I’d made it through. I watched people stumbling down the stairs into the capital’s cold. I’d made it. Where was the cab?