The Alcoholic & The Aviary

She was drunk on Friday

night and mistook herself for someone social, convivial, organising other

gatherings, agreeing to proposals, setting dates, leaving times till later,

to-be-confirmed’s. Yes, when she was drunk she was gregarious, but also especially

forgetful, so that when, the next day, she received a text from her sister,

stating—‘After three o’clock today is fine, or any time tomorrow,’ she walked

around the house asking anyone who had been present whether she had made

arrangements. Yes, she was told. Don’t you remember, she was asked. After more

champagne than her empty stomach could tolerate, she had said she would visit

her eldest sister, which was not something she usually did. The text scuppered

her plans to laze, but she could not rescind now, and agreed to go. She asked

me if I would like to join her. I was cleaning my room at the time, with a

documentary on in the background about a commune of paedophiles—Pervert Park—that

I was most amused by. It was warm in the room and I was quite sweaty. My uncle

is an alcoholic but always keeps a fridge of beer—for a reason I cannot quite determine;

perhaps guests, perhaps as a demonstration of willpower—and it would be my

sincere pleasure to take one of those cold beers off his hands. I told my

mother to leave without me, that I would catch her up once I had run the hoover

over. Not only did the free cold beer endow the visit with appeal, but it was a

chance to revisit my old walk; a walk that, after only six days, seemed like so

long ago and vaguer in the memory than I had expected.

Outside the air was very still and sticky, it did not move, it smothered, it was unpleasant and smelled of summer when she is trying not to throw up in the cab ride home. Because it was a Sunday, the forty-year-old couple were nowhere to be seen; every week day there is a couple who clean the retirement home, and at the time I used to go for walks they would withdraw to the van for fifteen minutes—one had to be careful to catch them—and they sat there, looking at me as I passed and I at them as they sat; I liked to imagine they were illicit lovers waiting for my disappearance before recommencing whatever fervent act I had interrupted. Instead, two young lovers cycled past, neither with any velocity or interest in the excursion, so burdensome was the heat. Indeed, I was already perspiring heavily and had not yet got down to the front. Despite my discomfort—and the fact that I was ruining a brand-new shirt—I was striding with great verve. The sight of the finches in the bush brightened my mood considerably, their fine little beaks; they scattered and recollected. If it were not so cruel, an aviary of finches one day on a property I own out in the country would be wonderful! What kind of monster could cage them? Not I. The covid testing facility manned by armed forces, nurses and security guards was absent at the weekend. I missed them, their well-coordinated operation, their queue of cars, windows down, speckled with blue masks.

Outside the air was very still and sticky, it did not move, it smothered, it was unpleasant and smelled of summer when she is trying not to throw up in the cab ride home. Because it was a Sunday, the forty-year-old couple were nowhere to be seen; every week day there is a couple who clean the retirement home, and at the time I used to go for walks they would withdraw to the van for fifteen minutes—one had to be careful to catch them—and they sat there, looking at me as I passed and I at them as they sat; I liked to imagine they were illicit lovers waiting for my disappearance before recommencing whatever fervent act I had interrupted. Instead, two young lovers cycled past, neither with any velocity or interest in the excursion, so burdensome was the heat. Indeed, I was already perspiring heavily and had not yet got down to the front. Despite my discomfort—and the fact that I was ruining a brand-new shirt—I was striding with great verve. The sight of the finches in the bush brightened my mood considerably, their fine little beaks; they scattered and recollected. If it were not so cruel, an aviary of finches one day on a property I own out in the country would be wonderful! What kind of monster could cage them? Not I. The covid testing facility manned by armed forces, nurses and security guards was absent at the weekend. I missed them, their well-coordinated operation, their queue of cars, windows down, speckled with blue masks.

What was that? I stopped

in my tracks and turned… Could it be? There was a new line of bitumen across

the pavement. There was doubt it was a new line of bitumen. How about that? I

disappear for a week and they carry out works on the pavement—‘He’s gone now.

We can take up the path!’ The new line of bitumen was very straight, pointing toward

the sea, lead the eye to the horizon where the water darkened in the distance. I

went on my way. Further along—and now terribly wet from sweat—I saw a branch in

the middle of the pavement. It was a branch I had seen a dozen times before.

About two weeks ago it appeared in the middle of the path, a sizeable branch, a

yard long, covered in leaves. Why, I had even noticed a man in front of me

once, with his prissy little west highland terrier, shift the branch out of the

way with clean tip of his boot, but now it was in the middle of the pavement

again! What is more, the leaves had all died. They were brown and stiff so

that, should I reach out and touch them, they would crackle and fall apart in

my fingers. It seems as if every bit of nutrition left in the branch had been

sipped, exhaled and exhausted. The dead of leaves. On my walks there were many

branches that had been puled from trees or snapped from the trunk and dangling

and every day I regarded them, curious as to how long the leaves would survive.

Well, here it was: the evidence right in front of me, the study concluded. I

smiled and carried on walking.

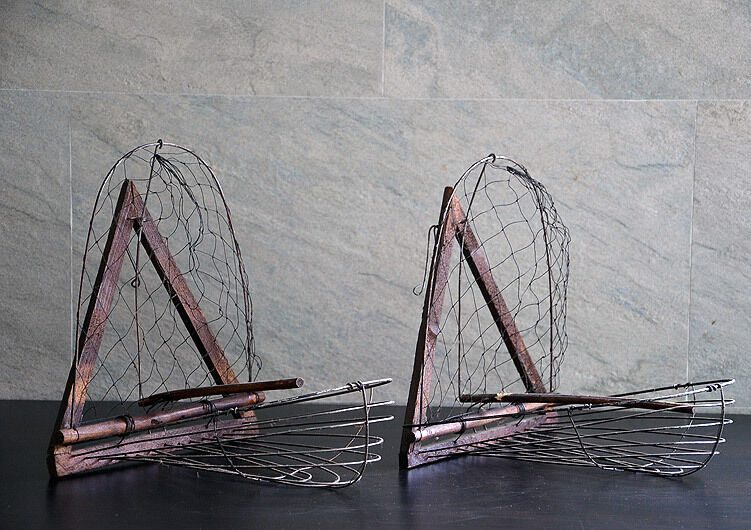

![]()

Bird Animal Trap Wooden

Aviary Cage Primitive Handmade, eBay

I would be a little late

to my aunt’s but there were sights along the route that I could not ignore. The

free cold beer was becoming even more tempting but I wished to prolong my

anticipation. Then I began to worry that … what if there was no free cold beer?

What if, leaving for a holiday in a couple of days, they had cleared the fridge

and drained them all down the sink? I panicked and picked up my pace. The side

gate was open and I entered their garden cautiously. One of my alcoholic uncles

was in the kitchen, drying his hands and reading a calendar. We greeted each

other. He offered me a cold beer. At first I pretended that I was not all that

fussed but would accept out of politeness. It was a pint can of my favourite

high-alcohol, low-cost lager, a rare find! Not stocked in my local off licence,

would not even fit within the refrigerator shelves. ‘No, it’s okay, I don’t

need a glass.’ Then my aunt emerged from the gloomy recesses of the house with

my mother and offered me a glass of cold water, and that I accepted gladly.

‘No, it’s okay, I don’t need ice.’ I swallowed it all in one go, feeling down

the length of my throat. I took the beer and walked around their garden. The

pear tree was shedding its fruit. The lawn around it was a pear graveyard, each

one in varying stages of decomposition. I gazed upon the rotting fruit and

drank my beer. Really, I could have stood in one spot and looked around the

garden, but I strolled leisurely, surveying, aiming to give off the appearance

of contemplation and appreciation. Put simply, I was enjoying being alone; I

liked to be alone knowing that there are people nearby. In the middle of the

lawn—almost exactly in the middle, as though placed by an architect—was a dead

mouse. It was only a tiny mouse but it was very dead. I bent down to study the

dead mouse and all the flies leapt off, apart from a stubborn wasp who would

not be disturbed from its meal. The mouse was freshly dead. Its innards, which

had spilled out, still had that butcher-shop window shine to them. You could

see its tiny bones and the flesh and the colour red and purple like the

sweetest blackberry. Its eyes were open. The wasp ate. The mouse watched the wasp

eating the flesh around its neck. The beer was nice and cold. ‘You got a dead

mouse here.’ My uncle was drinking some non-alcoholic beer—‘The cat must’ve got

to it. I blocked up its hole. Probably had nowhere to run.’ I frowned and stood

up.

After a couple of hours we

said good-bye far too many times and I walked home with my mother, just like we

used to do at the beginning of lockdown—albeit far hotter—and I was glad. There

were dandelions and daisies growing between the uneven paving slabs; was it

their little roots that so disrupted these blocks of stone? My mind became

flooded—what if now I should bring up all my worries, the weight on my mind, my

misery? It was opportune, but, no, why spoil the moment. I would keep it

secret. You tell people this sort of thing and it never helps. We made little

chatter. An old couple were outside a bungalow cleaning their motorcycle. ‘Look,’

said my mother—‘they have a motorcycle! They’re so unusual! She has that

sign inviting you to look at her painting in the window and smell her roses to

cheer yourself up.’ ‘I like them. They’re characters. She had out all her

sketches at the end of the drive, life drawings and shit … You ever see them?’ ‘No,

but I go out for my walks early. She’s probably not put them out by then … She

also used to have that stack of books you could help yourself to.’ ‘That’s right.

Yeah, I really like them.’ ‘Me too… Let’s go home and have a drink and order

junk food.’

![]()

Bird Animal Trap Wooden

Aviary Cage Primitive Handmade, eBay