Rustic Chivalry Within Touching Distance

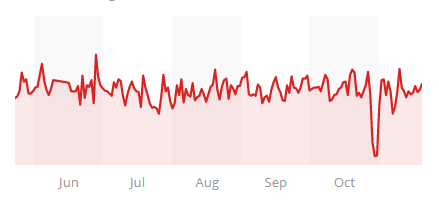

I do not know why there was something special about the

thirtieth of October, twenty-twenty, and, although I have evidence to support

this claim, I cannot explain it. The Italian opera composer Pietro Mascagni is

listened to everyday to the sum of – let us say – one hundred people, with a

loyal consistency that would be envied by any artist. Despite the fact that he

has been dead for the past seventy-five years, every day one hundred people

listen to his music, without fail, at least one piece, as regular as clockwork

and the trend is completely flat… except on the thirtieth of October

twenty-twenty. For some reason, on this date, the thirtieth of October,

twenty-twenty, among all others, those hundred people did not listen to his

music. Only thirteen did. I cannot understand what happened on that day for

eighty-seven people to not listen to Pietro Mascagni. There must be a reason,

but I cannot explain it. For two weeks now, since I made the discovery, I have pondered

over what might have happened on that unusual yet seemingly normal day when

eighty-seven people did not turn on their radio, or were perhaps too busy or

happy or sad to enjoy a single piece of his, of Pietro Mascagni’s. I will think

about it for a while yet; my curiosity does not close with this sentence.

![]()

There was something special about the twenty-first of November, twenty-nineteen. She and I arranged our week on a day-on, day-off basis, so that, for the weekdays at least, every night we spent on the town would be followed by an evening at home, in the interests of dynamics, energy and finance. On that particular day, a Thursday, she would text me with suggestions of where to eat in the evening, and, emerging from meetings – Thursday being the busiest – I would consider each and offer my two-pence. We narrowed it down to three options, and then one. There was a mighty cold wind blowing off the river and it was silver. She asked me what I thought she should wear: jeans or a dress. She thought it might be too cold for a dress, between the buildings and the city’s channels. I told her to wear the dress and black tights, so that I might see the shape of her legs, because they were such good legs and so shapely. She complied and was left waiting for me outside of my office building for so long amongst the sleet that tumbled she was ushered into the supermarket for warmth. Apologies as I put my fingers against the perfect black expanse of tights’ thigh. We went to the pub, the table not booked until eight o’clock, and there we drank. She wore all black. It was warm in the pub, humid gusts of human exhalations rushing between tables. The creak of old beer dripped between cracks of varnished wood. Many times I had been to that pub, often in dark hours, and so one never knows when things will all work out, even if for just an evening. It was no time at all before all ours had passed and we were obliged to take leave and head to the restaurant for dinner. She was such good drinking company that I could have spent all evening there with her; those times always so delightful that they flash before me, and then, throughout the course of my life, so brief that they seem as though they hardly existed at all.

Pietro Mascagni’s scrobbles the past six months

There was something special about the twenty-first of November, twenty-nineteen. She and I arranged our week on a day-on, day-off basis, so that, for the weekdays at least, every night we spent on the town would be followed by an evening at home, in the interests of dynamics, energy and finance. On that particular day, a Thursday, she would text me with suggestions of where to eat in the evening, and, emerging from meetings – Thursday being the busiest – I would consider each and offer my two-pence. We narrowed it down to three options, and then one. There was a mighty cold wind blowing off the river and it was silver. She asked me what I thought she should wear: jeans or a dress. She thought it might be too cold for a dress, between the buildings and the city’s channels. I told her to wear the dress and black tights, so that I might see the shape of her legs, because they were such good legs and so shapely. She complied and was left waiting for me outside of my office building for so long amongst the sleet that tumbled she was ushered into the supermarket for warmth. Apologies as I put my fingers against the perfect black expanse of tights’ thigh. We went to the pub, the table not booked until eight o’clock, and there we drank. She wore all black. It was warm in the pub, humid gusts of human exhalations rushing between tables. The creak of old beer dripped between cracks of varnished wood. Many times I had been to that pub, often in dark hours, and so one never knows when things will all work out, even if for just an evening. It was no time at all before all ours had passed and we were obliged to take leave and head to the restaurant for dinner. She was such good drinking company that I could have spent all evening there with her; those times always so delightful that they flash before me, and then, throughout the course of my life, so brief that they seem as though they hardly existed at all.

After waiting in the doorway for a quick minute, we were

guided most politely to our table down an aisle of elbows and shoulders illuminated

harshly by the bright lights overhead. Everyone was within touching-distance;

to extend the arm and be greeted by another’s shoulder, to glance without mask,

to be awash in the festival of human’s subtle joy over platters of Vietnamese

food! The smells and atmosphere of deliciousness, of metal on china, the small

organisation of couples and cohorts, colleagues and hunger underneath stark

fluorescent lamps. Bringing her elbows upon the cloth, she leaned in closer;

inches between our eyes, an inch between our knees, no inch at all. I did not

have my camera with me so that, in a year’s time, I might struggle to recollect

her projection of colour, the splendour of her form, the luminous pink of her

eye shadow, the point of her mascara and unadorned brows that were so thick so

devilish as she sipped her Vietnamese beer and laughed. Thin wrists elevated to

cutely adjust the hair that had been blown from its position. It is beyond the

writer to describe or articulate the wonder of her presence, not even the key

of her humour or the happiness of her conversation. So the burden of it all

rests on the relation of how light caught the tendons that stretched up her

arms, or the star & moon earrings she wore, so grand and sparkly that, if I

think back, a year exactly, then I can only do it all a disservice. Winter

coats hung from the back of each chair, like plinths under busts. She spoke and

our dishes were placed before us.

We were more than halfway through our time together, and it lingered in our thoughts always, but we pushed it away, certainly not daring to say a word about it out loud. We got home, put Drag Race on and undressed. Afterwards we lay there, catching our breath, drying in the radiator air, and gazing at Antiques Roadshow, because she really enjoyed it and I playing with her hair, thinking silently that it would soon be the weekend and after the weekend she would be gone. The thought weighed so heavily upon me! The volume was low, the room quiet, I stared without seeing.

The next evening, she met some of my friends, an impromptu arrangement at the venue in which I had seen her for the first time in over six years only a month prior. Before, The Phoenix had been just a pub without any particularly rich memories, somewhere I drank dispassionately but often, feeling for it merely the kind of fondness of familiarity that one holds for their most-frequented watering hole. Then she arrived, and with the gentle planting of a kiss, made the site memorable, unforgettable, as I found she could with the slightest movement, expression, or glance, imprint the moment permanently upon my psyche. It was until we stood, away from the table around which our company of eight congregated, that we came to rest and talk peacefully to each other. True, proximity was not in my nature, nor was it to recoil, but she came so close, so close she stood her feet on mine next to mine, touching her body till our bodies touched along their height. Our words so close, too, that they fed into the other’s mouth. Her breath caught in my beard. Finally, at something or nothing at all, she rested her head on mine. The few inches I have over her placed my lips against the sweet oils on her forehead; my nostrils in the garden of her parting. She relaxed, her breathing chest and mine, warmth multiplying, the transfixion of no more than two minutes, absolute bliss conjured by an action no one had ever visited upon me before. That it should be so simple! Nobody else was there. The Phoenix was empty. And then it returned, the punters and the noise, the clinking glass, the music, the traffic through tall windows. Soon she would be gone, I thought. Soon it would be a year, I wrote.

We were more than halfway through our time together, and it lingered in our thoughts always, but we pushed it away, certainly not daring to say a word about it out loud. We got home, put Drag Race on and undressed. Afterwards we lay there, catching our breath, drying in the radiator air, and gazing at Antiques Roadshow, because she really enjoyed it and I playing with her hair, thinking silently that it would soon be the weekend and after the weekend she would be gone. The thought weighed so heavily upon me! The volume was low, the room quiet, I stared without seeing.

The next evening, she met some of my friends, an impromptu arrangement at the venue in which I had seen her for the first time in over six years only a month prior. Before, The Phoenix had been just a pub without any particularly rich memories, somewhere I drank dispassionately but often, feeling for it merely the kind of fondness of familiarity that one holds for their most-frequented watering hole. Then she arrived, and with the gentle planting of a kiss, made the site memorable, unforgettable, as I found she could with the slightest movement, expression, or glance, imprint the moment permanently upon my psyche. It was until we stood, away from the table around which our company of eight congregated, that we came to rest and talk peacefully to each other. True, proximity was not in my nature, nor was it to recoil, but she came so close, so close she stood her feet on mine next to mine, touching her body till our bodies touched along their height. Our words so close, too, that they fed into the other’s mouth. Her breath caught in my beard. Finally, at something or nothing at all, she rested her head on mine. The few inches I have over her placed my lips against the sweet oils on her forehead; my nostrils in the garden of her parting. She relaxed, her breathing chest and mine, warmth multiplying, the transfixion of no more than two minutes, absolute bliss conjured by an action no one had ever visited upon me before. That it should be so simple! Nobody else was there. The Phoenix was empty. And then it returned, the punters and the noise, the clinking glass, the music, the traffic through tall windows. Soon she would be gone, I thought. Soon it would be a year, I wrote.