Old Stores

The sash windows, their glass old and thin, seals crumbling with age, steamed up from the hot shower I had just taken. Shutters folded inwards on stiff hinges, the heavy curtains were tied back, and on the first morning tiny spiders descended on tinier threads from the pelmet at my disruption. Only one of the windows could be raised and every morning it was, to air the room of odour and heat. Around the window ran vines of ivy. I looked out underneath the raised sash, carefully, dressed only in a towel, at the people that gathered below.

The most popular place in the village was a café by the name of The Old Store and it was located just outside my bedroom window, and at the hour I emerged from my morning shower a considerable queue had already formed at its door as punters waited for somewhere to sit inside. The people queued not in a straight line, but all over the place, muddled, although in a village where everyone knew each other, this was not a problem at all. All of them were well dressed for country walks and all of them were handsome. Their dogs heeled at the end of slack leads. Occasionally a waitress would open the door and call from the threshold—‘A two?’ and a couple would go in, taking their dog with them—‘Do you mind the window? It’s warm there, with the sun.’ I did the buttons of my shirt, went downstairs, put my trainers on and walked out the back door. So deliciously cold. Crows in the tree above me cawed out a warning that I was passing by. Inside of The Old Store it was noisy, chaotic and close; young families and hounds, sometimes three generations, toddlers being calmed, a biscuit slipped to a waiting mouth under the table, service dodging by with flying saucer trays, the kitchen passing loaves in and out the ovens, the coffee machine wand hissing, grinder whirring, a portafilter gurgling; asked the girl at the till with a good smileful of braces if I could have a cappuccino, please. ‘You can wait outside,’ she told me. Aware that I was a stranger, an outsider, I kept my head down and felt the heat of the February sun on the back of my neck. A Scandinavian-looking woman with a braid tied ornately around her bright blonde hair came out to me—‘I didn’t give you any chocolate because I know you don’t like it.’ Blushing, I hurried off.

The whole village spread out from The Old Store at its centre. From there and the coffee cup, everybody expanded outwards.

In the village was the country house, in the country house was my bedroom. The country house had a heat and an odour that dissipated a little when I raised my sash window every morning. In the rest of the country house was my cat, my parents, my brother & his girlfriend, my other brother & his family, and four pairs of aunt & uncle. Two foil balloons in the shape of 6 and 5 floated in the dining room. Empty bottles of champagne collected next to the bin. Leftover food was wrapped in clingfilm and placed on the side or in the fridge. Throughout the house there were many different conversations going on, little clusters of activity, different voices and different volumes. The cat had spent the morning exploring and, laying eyes on me, hurried over to say hello, her cheek scenting my leg. It was quiet in the front room, just my father on his laptop, just the lumps in the old sofa, lumps that had formed after godknowshowmanyyears of bodies flopping and shifting, of a body stretching itself out with a novel in its hand.

The night before, I had received a series of messages in quick succession—How is the travel going?... In the plane to Dublin, my friend missed it [upside-down smiley-face]… She’s taking the next one… Means I can only do one thing… read thinking of you [grinning-face with sweat] I can read, I cannot read. The more I went back to it, the more I struggled to understand. Everything I found beautiful she thought was melancholic—and she smiled at me. Of all complications! I find it far simpler to stand beneath the tree looking up at the crows that caw out a warning as around my ankles tender shoots arise. They are so colourful there in the daintiest of winter light. Among long pauses of nightly preparations, as guests of the country house took to their bathrooms before dinner, I pulled the coat tight about my throat and walked around the village. There was nobody on the streets or down the lanes or along the avenues, all the handsome people were home, and all the homes were warm, all the fires lit. I went to the local Co-op and bought a small pot of double cream. A wind was thrown through the road; it hurt the skin of my face. ‘What’s wrong with your face?!’ my aunt had gasped when I opened the door at her arrival, rice cooker in one hand and a suitcase in the other. I told her that this is my skin, that this is just my skin, what my skin always looks like. ‘O,’ she said—‘I thought you’d had an allergic reaction or something.’ And she grunted the rice cooker and suitcase up the worn old steps as I kept an eye open for the cat, who poked her head through the banister to observe their entry. How easy it is to be miserable at the state of the skin I am in! I arrived back at the silent country house to find the cat exploring—for the twelfth time—the shelf of cooking utensils, pots, saucepans, bowls, her tiny head covered in spiderwebs—‘Look at the mess you’re in!’ says I, pawing them off her.

The most popular place in the village was a café by the name of The Old Store and it was located just outside my bedroom window, and at the hour I emerged from my morning shower a considerable queue had already formed at its door as punters waited for somewhere to sit inside. The people queued not in a straight line, but all over the place, muddled, although in a village where everyone knew each other, this was not a problem at all. All of them were well dressed for country walks and all of them were handsome. Their dogs heeled at the end of slack leads. Occasionally a waitress would open the door and call from the threshold—‘A two?’ and a couple would go in, taking their dog with them—‘Do you mind the window? It’s warm there, with the sun.’ I did the buttons of my shirt, went downstairs, put my trainers on and walked out the back door. So deliciously cold. Crows in the tree above me cawed out a warning that I was passing by. Inside of The Old Store it was noisy, chaotic and close; young families and hounds, sometimes three generations, toddlers being calmed, a biscuit slipped to a waiting mouth under the table, service dodging by with flying saucer trays, the kitchen passing loaves in and out the ovens, the coffee machine wand hissing, grinder whirring, a portafilter gurgling; asked the girl at the till with a good smileful of braces if I could have a cappuccino, please. ‘You can wait outside,’ she told me. Aware that I was a stranger, an outsider, I kept my head down and felt the heat of the February sun on the back of my neck. A Scandinavian-looking woman with a braid tied ornately around her bright blonde hair came out to me—‘I didn’t give you any chocolate because I know you don’t like it.’ Blushing, I hurried off.

The whole village spread out from The Old Store at its centre. From there and the coffee cup, everybody expanded outwards.

In the village was the country house, in the country house was my bedroom. The country house had a heat and an odour that dissipated a little when I raised my sash window every morning. In the rest of the country house was my cat, my parents, my brother & his girlfriend, my other brother & his family, and four pairs of aunt & uncle. Two foil balloons in the shape of 6 and 5 floated in the dining room. Empty bottles of champagne collected next to the bin. Leftover food was wrapped in clingfilm and placed on the side or in the fridge. Throughout the house there were many different conversations going on, little clusters of activity, different voices and different volumes. The cat had spent the morning exploring and, laying eyes on me, hurried over to say hello, her cheek scenting my leg. It was quiet in the front room, just my father on his laptop, just the lumps in the old sofa, lumps that had formed after godknowshowmanyyears of bodies flopping and shifting, of a body stretching itself out with a novel in its hand.

The night before, I had received a series of messages in quick succession—How is the travel going?... In the plane to Dublin, my friend missed it [upside-down smiley-face]… She’s taking the next one… Means I can only do one thing… read thinking of you [grinning-face with sweat] I can read, I cannot read. The more I went back to it, the more I struggled to understand. Everything I found beautiful she thought was melancholic—and she smiled at me. Of all complications! I find it far simpler to stand beneath the tree looking up at the crows that caw out a warning as around my ankles tender shoots arise. They are so colourful there in the daintiest of winter light. Among long pauses of nightly preparations, as guests of the country house took to their bathrooms before dinner, I pulled the coat tight about my throat and walked around the village. There was nobody on the streets or down the lanes or along the avenues, all the handsome people were home, and all the homes were warm, all the fires lit. I went to the local Co-op and bought a small pot of double cream. A wind was thrown through the road; it hurt the skin of my face. ‘What’s wrong with your face?!’ my aunt had gasped when I opened the door at her arrival, rice cooker in one hand and a suitcase in the other. I told her that this is my skin, that this is just my skin, what my skin always looks like. ‘O,’ she said—‘I thought you’d had an allergic reaction or something.’ And she grunted the rice cooker and suitcase up the worn old steps as I kept an eye open for the cat, who poked her head through the banister to observe their entry. How easy it is to be miserable at the state of the skin I am in! I arrived back at the silent country house to find the cat exploring—for the twelfth time—the shelf of cooking utensils, pots, saucepans, bowls, her tiny head covered in spiderwebs—‘Look at the mess you’re in!’ says I, pawing them off her.

On the first night, we had a takeaway curry. On the second night, I made pasta alla norcina. On the third night, a hired chef cooked griddle cakes and steak. On the fourth night, my aunts cooked curry with chickpeas, chapatis and pepper water.

On the fifth day, my parents and I went for a walk. The aunts and uncles had divided up the remaining fruitcake, loaded up their cars and disappeared down the road. With the country house quieter, I was more inclined to breath out a little deeper. And so, that sunny Sunday afternoon, the three of us passed the village school and its sportsfield boundary, out the trailing capillaries pointing away from The Old Stores. My mother pointed at the church on a Sabbath and how we were getting farther away from it. ‘Are you not cold?’ I wore only my shirt. It was brisk; I pushed my jaw out as I said it—‘Brisk, brisk, brisk.’ A small stream from our weeks-of-rain ran down the pebbles we stepped over. At a turn in the road, a cottage’s tree leaned over the stonewall, holding its minor petals quite pinkly over the verge. The three of us, in boots and wellies, cut around a farm as the stench of ammonia and brittle smell of cold hay poured over the valley. There were horses grazing, frozen in their pose, piffles of steam out their downward nostrils. My mother, father and I walked along clumsily in our footwear. How did those manicured patrons outside The Old Stores negotiate the mud? With more elegance, certainly! We walked to the bottom of the valley so my father could point out a very uninteresting stream. My mother carried an Instaxcamera in her hand, snapping occasionally and then holding the developing piece in the air for five minutes like a winning lottery ticket. We went on for a few miles; everything we recognised disappeared into a distance of indistinguishable countryside. My father and I huddled over the map.

I told them—‘When you’re in the countryside—rambling and that—you have to use words like “outcrop”, “thicket” and “hedgerow.” Words that have absolutely no application anywhere else.’

My father interrupted—‘When we get to the top of the hill, we have to look out for a pair of electrical masts on our right.’

‘No, no, you have to say shit like—“Turn eastward at the brambly thicket.”’

My mother—‘There are two electrical masts!’

‘…Are they at the top of the hill on our right?’

‘…No.’

‘What are those?’

‘Sugar beets, I think.’

Perhaps it is because my life—this life—is so empty and without purpose, that the pinnacle of beauty can be found in the scuffle of footwear across country roads, desolate and dry, hemmed in on each side by muddy grass banks, and the distance of Norfolk extended, or maybe, amongst the complexity of earthy terrors, something so simple and undistorted can become the highlight of one’s day. At the crossroads, my father suggested we shift towards the church.

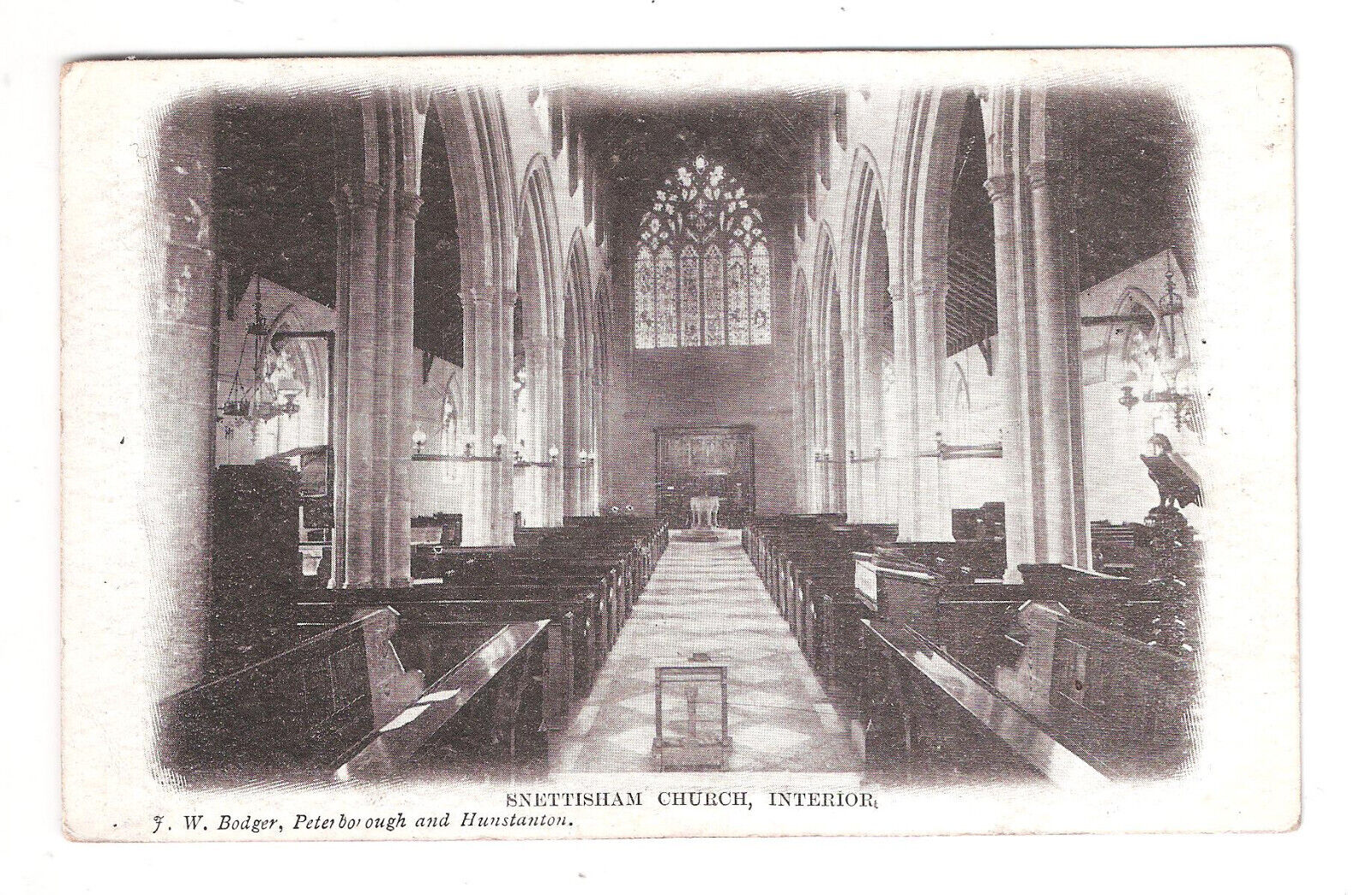

We came in through the rear, intruding a rusted iron gate that clung to its hinges, walking tired and impatient through the graveyard. ‘It’s lovely in there. Come in!’ I told him I would not take my muddy wellies into the church. My mother thought the same, so we both waited as he wandered inside.

The church sat not in the village but on its outskirts, separate, excluded, or maybe voluntarily apart. The church sat on a slight hill. The church overlooked all those who ran into its belly. The church sat in a nest of graves as old as stone. The church sat in the middle of a flock of rambunctious ducks. The church sat smugly in a before me and after me. The church sat in a constant, like our sun or Jupiter’s moons.

I thought of all the local villagers who might have died during the construction of the church, and I smiled, for I could still not take my soiled soles between the pews. The three of us—yes! three!—said hello to those we crossed paths with. There must be some special power in the wellies, I surmised, an unfathomable friendliness. The sun was exhausted by the time we got back. A couple of card games later and it was not much of a walk to the local pub; dead; end of half-term sleepiness.

I wanted to look again upon the church, but no, it was out there in the dark, out of reach and invisible My belly had only delicious food swilled and disintegrating within. Ale came up my throat. We could not see our dark route back to the country house but for lanterns at the pub entrance. We were merry and joked. There had been a lot of that: merriment and jokes.

On the fifth day, my parents and I went for a walk. The aunts and uncles had divided up the remaining fruitcake, loaded up their cars and disappeared down the road. With the country house quieter, I was more inclined to breath out a little deeper. And so, that sunny Sunday afternoon, the three of us passed the village school and its sportsfield boundary, out the trailing capillaries pointing away from The Old Stores. My mother pointed at the church on a Sabbath and how we were getting farther away from it. ‘Are you not cold?’ I wore only my shirt. It was brisk; I pushed my jaw out as I said it—‘Brisk, brisk, brisk.’ A small stream from our weeks-of-rain ran down the pebbles we stepped over. At a turn in the road, a cottage’s tree leaned over the stonewall, holding its minor petals quite pinkly over the verge. The three of us, in boots and wellies, cut around a farm as the stench of ammonia and brittle smell of cold hay poured over the valley. There were horses grazing, frozen in their pose, piffles of steam out their downward nostrils. My mother, father and I walked along clumsily in our footwear. How did those manicured patrons outside The Old Stores negotiate the mud? With more elegance, certainly! We walked to the bottom of the valley so my father could point out a very uninteresting stream. My mother carried an Instaxcamera in her hand, snapping occasionally and then holding the developing piece in the air for five minutes like a winning lottery ticket. We went on for a few miles; everything we recognised disappeared into a distance of indistinguishable countryside. My father and I huddled over the map.

I told them—‘When you’re in the countryside—rambling and that—you have to use words like “outcrop”, “thicket” and “hedgerow.” Words that have absolutely no application anywhere else.’

My father interrupted—‘When we get to the top of the hill, we have to look out for a pair of electrical masts on our right.’

‘No, no, you have to say shit like—“Turn eastward at the brambly thicket.”’

My mother—‘There are two electrical masts!’

‘…Are they at the top of the hill on our right?’

‘…No.’

‘What are those?’

‘Sugar beets, I think.’

Perhaps it is because my life—this life—is so empty and without purpose, that the pinnacle of beauty can be found in the scuffle of footwear across country roads, desolate and dry, hemmed in on each side by muddy grass banks, and the distance of Norfolk extended, or maybe, amongst the complexity of earthy terrors, something so simple and undistorted can become the highlight of one’s day. At the crossroads, my father suggested we shift towards the church.

We came in through the rear, intruding a rusted iron gate that clung to its hinges, walking tired and impatient through the graveyard. ‘It’s lovely in there. Come in!’ I told him I would not take my muddy wellies into the church. My mother thought the same, so we both waited as he wandered inside.

The church sat not in the village but on its outskirts, separate, excluded, or maybe voluntarily apart. The church sat on a slight hill. The church overlooked all those who ran into its belly. The church sat in a nest of graves as old as stone. The church sat in the middle of a flock of rambunctious ducks. The church sat smugly in a before me and after me. The church sat in a constant, like our sun or Jupiter’s moons.

I thought of all the local villagers who might have died during the construction of the church, and I smiled, for I could still not take my soiled soles between the pews. The three of us—yes! three!—said hello to those we crossed paths with. There must be some special power in the wellies, I surmised, an unfathomable friendliness. The sun was exhausted by the time we got back. A couple of card games later and it was not much of a walk to the local pub; dead; end of half-term sleepiness.

I wanted to look again upon the church, but no, it was out there in the dark, out of reach and invisible My belly had only delicious food swilled and disintegrating within. Ale came up my throat. We could not see our dark route back to the country house but for lanterns at the pub entrance. We were merry and joked. There had been a lot of that: merriment and jokes.