Obtuse

Back at the

start of the pandemic, when everyone thought ‘a-month-at-best’, and there was a

novelty in the mild terror, supermarket shortages and unusual predicament, my

mother and I would go for walks along the seafront. I was still paying rent on

my empty flat, still believing that my relationship would survive, still growing

accustomed to the chill of the coast so different to that of the city. The

walks would end by the summer, when it grew too hot for my mother, but back

then it was late winter, and our walks together after lunch were cherished. We

would talk, sometimes I would not say a word; seldom would I feel confessional,

or anything beyond the pitter-patter of informal conversations about family,

weather and what’s for dinner. Like much of what comes to be remembered with full

softness of the heart, those walks with my mother did not feel so special at

the time.

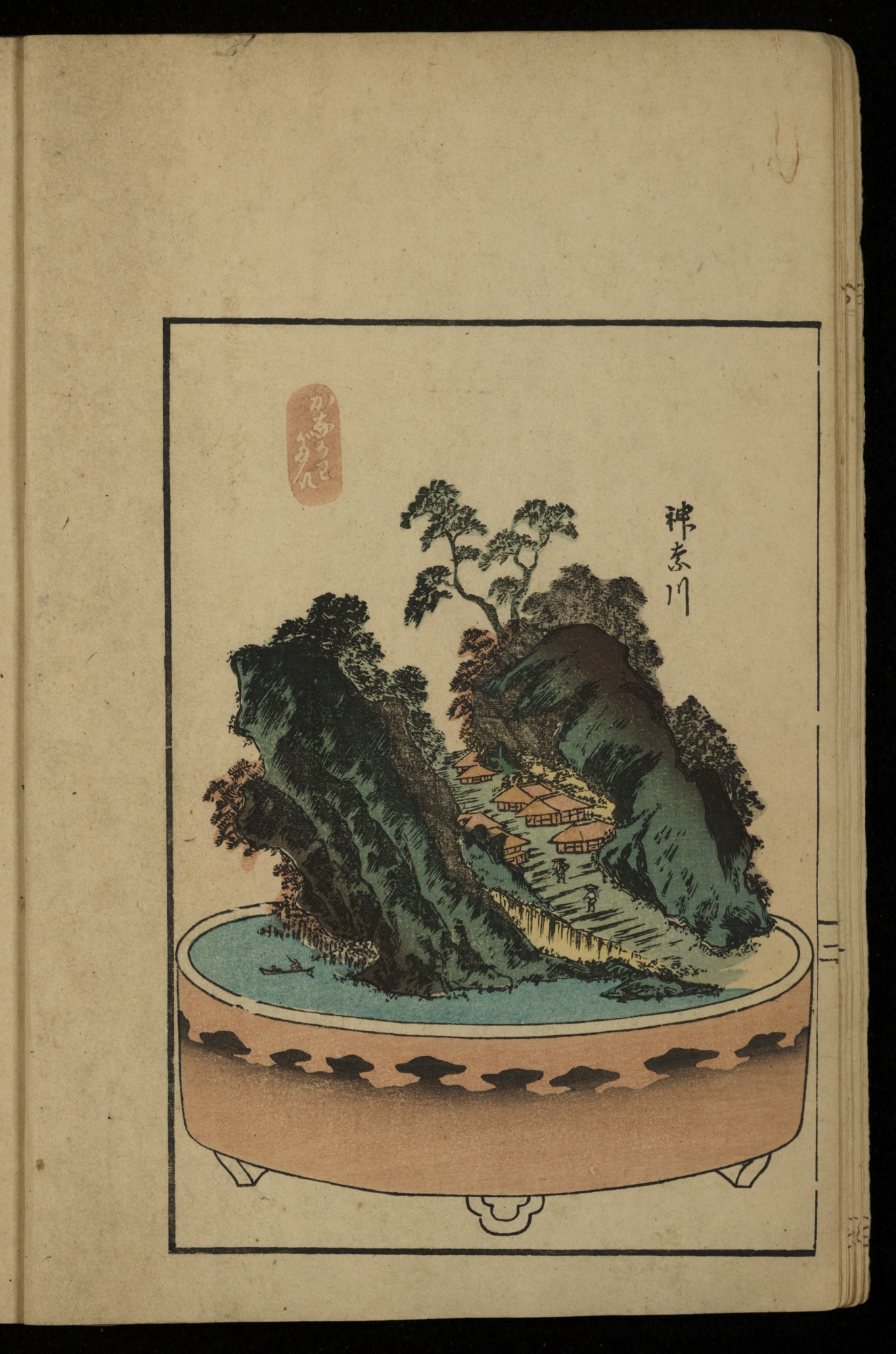

At the tip of an outcrop of land above the beach, there was a tree. It jutted out at an obtuse angle from the soil, away from the earth and toward the sea, yet its branches and leaves turned back, grown and growing away for the waves. It became a lighthouse of sorts; its impression from the promenade infallible on the horizon, its shape very much like conflict, its limbs like bonsai, its shadow across the sky like a lungful of atmosphere. In the depth of its shadows was the black of nature and time. The banks around it had begun to collapse. Already a shaft of soil had fallen away into the back of a beach hut, splitting and bowing out its wooden sides like the jaw of a whale (as I wrote at the time). All was precarious. Every day we walked past and I wondered if my ears would ever be sensitive enough to rustle at me the shifting of soil beneath the surface. Rain that fell on the banks eventually ran down and trickled clearly towards the edge of the sea, as though it craved to be reunited with its whitecrested brothers and sisters. The trickle formed little streams in the sand, shot that mustard texture across with brown lines and curve.

At the tip of an outcrop of land above the beach, there was a tree. It jutted out at an obtuse angle from the soil, away from the earth and toward the sea, yet its branches and leaves turned back, grown and growing away for the waves. It became a lighthouse of sorts; its impression from the promenade infallible on the horizon, its shape very much like conflict, its limbs like bonsai, its shadow across the sky like a lungful of atmosphere. In the depth of its shadows was the black of nature and time. The banks around it had begun to collapse. Already a shaft of soil had fallen away into the back of a beach hut, splitting and bowing out its wooden sides like the jaw of a whale (as I wrote at the time). All was precarious. Every day we walked past and I wondered if my ears would ever be sensitive enough to rustle at me the shifting of soil beneath the surface. Rain that fell on the banks eventually ran down and trickled clearly towards the edge of the sea, as though it craved to be reunited with its whitecrested brothers and sisters. The trickle formed little streams in the sand, shot that mustard texture across with brown lines and curve.

Another portion

of the bank collapsed, signing a death sentence for the tree and it was chopped

down three weeks later.

It was a beautiful tree, mourned, if only by I on my then-autumnal walks along the sand swept promenade.

However, the roots remained, tied to half-a-foot of trunk that poked above the ruptured earth. It would not recover. Nor would the bank. At any moment it might subside. When it slid, so many fortunate and attractive shapes arose.

At the end of summer, they cordoned off that section of the beach. Every day I walked past. Thick wooden posts were sunk into the condemned stretch of bank, set in concrete, strong enough for the wind. Thin wooden boards were drilled to the posts, shielding the area from entry and observation. The tree was finally pulled out, roots and all. The bank was dug out, reconstructed. Everything about the tree was gone. When out on a walk, if one looked up, there was an empty passage of air where it had flourished. You can see the gulls there, looking for worms within the upturned soil. Perhaps they will plant another tree in its place, a tree so twisted and perfect that during the next global pandemic someone not even born yet will look up and remark with wintery satisfaction—‘What a twisted and perfect tree!’

It was a beautiful tree, mourned, if only by I on my then-autumnal walks along the sand swept promenade.

However, the roots remained, tied to half-a-foot of trunk that poked above the ruptured earth. It would not recover. Nor would the bank. At any moment it might subside. When it slid, so many fortunate and attractive shapes arose.

At the end of summer, they cordoned off that section of the beach. Every day I walked past. Thick wooden posts were sunk into the condemned stretch of bank, set in concrete, strong enough for the wind. Thin wooden boards were drilled to the posts, shielding the area from entry and observation. The tree was finally pulled out, roots and all. The bank was dug out, reconstructed. Everything about the tree was gone. When out on a walk, if one looked up, there was an empty passage of air where it had flourished. You can see the gulls there, looking for worms within the upturned soil. Perhaps they will plant another tree in its place, a tree so twisted and perfect that during the next global pandemic someone not even born yet will look up and remark with wintery satisfaction—‘What a twisted and perfect tree!’