Naught But Pistachio Shells

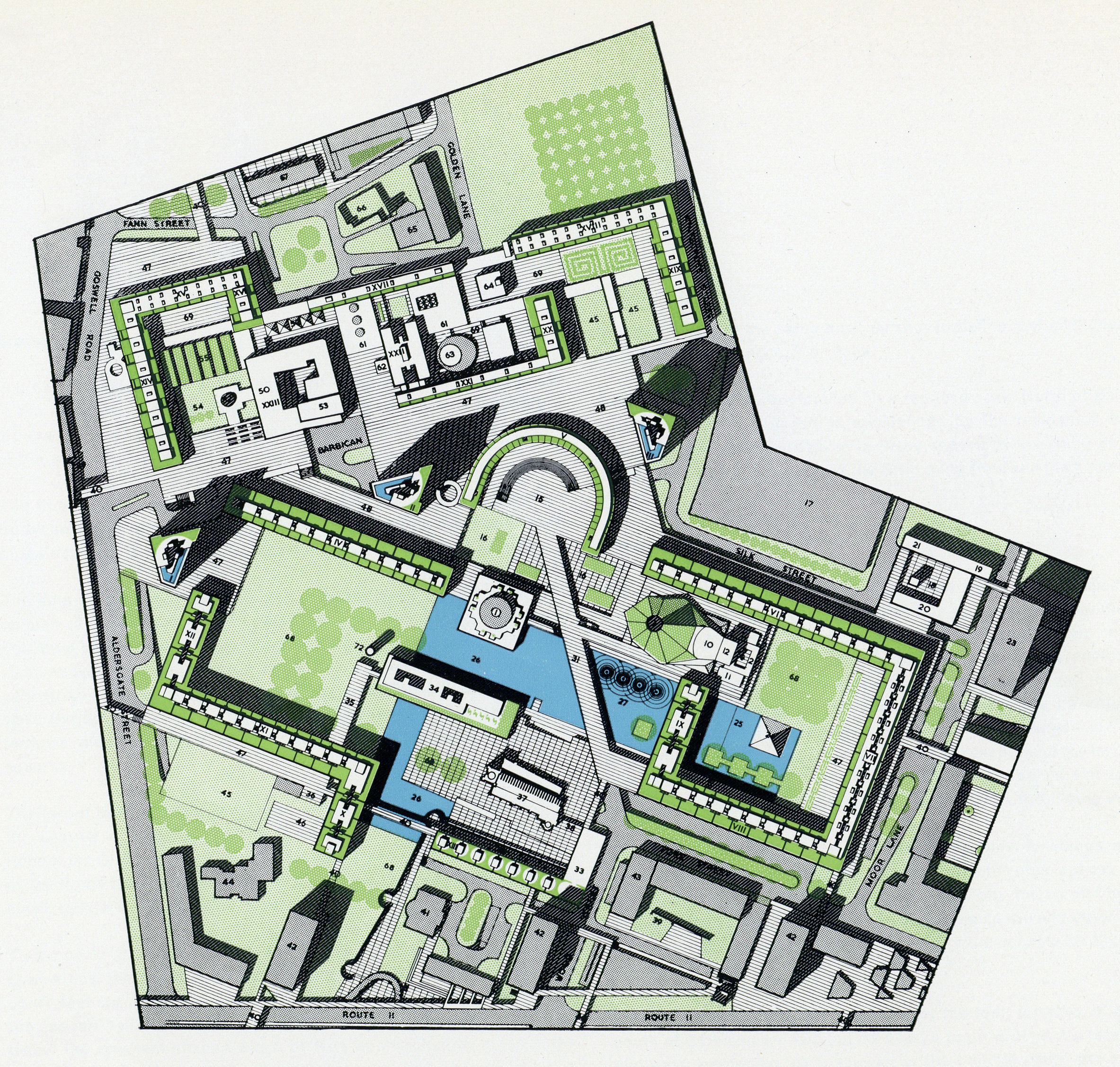

They looked like human teeth and there seemed to be as much as a mouthful, too. Although they were not human teeth, they looked like human teeth and that is perhaps why they leapt out to me. Who else did they leap out to, who else thought they might be human teeth? They were naught but pistachio shells. (My parents have a special bowl for pistachios, a special bowl with a special little clay corner for the shells; the crumbs, skin, are flecked all around; my father is a messy eater, messy & loud, so that the crumbs are everywhere. Both my parents hunch over the bowl, eating pistachios.) These were not the pistachio shells I saw that looked like human teeth, no, these pistachio shells had been discarded underneath one of the incoming gas supplies to the Barbican. It is a large gas supply—ten-inch, maybe—and it trunked up out the pavement into a meter room that shone dull with grease, valves, a bulbous governor, gauges, schematics and a plastic chair for maintenance. The shells had been there for months. They had not lost their lustre; the brightness they had possessed when they were first separated from their cargo remained, semi-exposed as they were beneath the pipework, cinema and shade of Cromwell Tower. I picture someone passing their time beside one of the incoming gas supplies to the Barbican with a handful of pistachios. Who knows what they were waiting for. They waited, they ate pistachios, they threw the shells just on the floor there. It was a feckless art installation. Not even the rats would take the shells away, they respect the culture.

The pistachio is a fruit and its flesh is green. The green of the pistachio is one of the most beautiful greens and that is why humans took the fruit for themselves and sold pistachios in supermarkets. Despite human interference, the green of the pistachio is one of the most beautiful greens and that is why a streetcleaner finally came along and took the shells away. The shell is to the pistachio what the full-stop is to the sentence; the sentence is the important part but it cannot come to be anywhere unless it is carried there by the full-stop. The shells were carried away by a streetcleaner. There must have been a reason the streetcleaner took those shells away that day and not any other. Maybe it was a new streetcleaner, new to the job, thorough, meticulous, looking to make a good impression; maybe the inspection board were doing the rounds that day. The shells were gone.

The only story of mine ever published was about pistachios. It was about pistachios and death.

On a day when brisk spring is bypassed for warm summer, a hand hangs out an open car window, passenger-side. Caught at the junction by the prison, standstill. The hand is exemplary. It is limp. When a hand is limp it is natural like a body out the shower or a microphone on stage. An engagement ring catches the sun’s light coming over the prison wall.

The pistachio is a fruit and its flesh is green. The green of the pistachio is one of the most beautiful greens and that is why humans took the fruit for themselves and sold pistachios in supermarkets. Despite human interference, the green of the pistachio is one of the most beautiful greens and that is why a streetcleaner finally came along and took the shells away. The shell is to the pistachio what the full-stop is to the sentence; the sentence is the important part but it cannot come to be anywhere unless it is carried there by the full-stop. The shells were carried away by a streetcleaner. There must have been a reason the streetcleaner took those shells away that day and not any other. Maybe it was a new streetcleaner, new to the job, thorough, meticulous, looking to make a good impression; maybe the inspection board were doing the rounds that day. The shells were gone.

The only story of mine ever published was about pistachios. It was about pistachios and death.

On a day when brisk spring is bypassed for warm summer, a hand hangs out an open car window, passenger-side. Caught at the junction by the prison, standstill. The hand is exemplary. It is limp. When a hand is limp it is natural like a body out the shower or a microphone on stage. An engagement ring catches the sun’s light coming over the prison wall.

I am lonely and within reach; perspiration keeps the backpack stuck to my back; the hand is close enough to hold, the ring precious enough to steal. I am alongside the great walls of the prison. All the souls inside, behind brick and iron. Many of the houses down from the prison put their unwanted possessions out on the pavement. A cardboard strip—FREE in broad strokes of black. On a day when brisk spring is bypassed for warm summer, a deck of Uno cards had come loose and blown along the way. It was nothing, really, but the cards had blown down along the way, and it just seemed strange to me that they should line my path like waving palms. I wiped the perspiration from my brow with the blunt of my wrist.

I had pistachios on the brain. You see something in the same place for so many days over so many months over so many seasons, and you become affected when it is gone. I was sure to get over it. I came home and ate lunch, emptied the washing machine, I put all the groceries away. Terrible the tiredness! terrible the mood! but I was keen to overturn them. I took a mop to my forehead. I said good-bye to the cat. It was warm. There were nerves, but I was very miserable of being so silly alone. The day was wonderful and everything was clear, in a plush haze; during my teenage years I would have become tumescent, in my late thirties I was alive and it was, at best, enough. The store was busy and I looked at the stock. An employee asked me if I was okay, and I told them I was. Not two minutes later I asked how I might join one of the card games. They played with their feet, then stared out over the tables and ruckus of various games going on. They approached one table after another, explaining things. The occupying players turned and regarded me. Finally they came back—‘That lot over there can get you into a game. They’re just shifting things around.’ I stood by them and said my name aloud. They said hello and asked me some questions, friendly before a tabletop of cards that made some sort of sense. One of the men stood up and took me to a nearby table, assuring that it was no bother, and we set up for a match. His hand swooped and pointed, a new vocabulary flowing from his tongue, a bright enthusiasm.

Two hours later, I left with a tremendous sense of optimism and friendliness, an unfamiliar duet putting flourishes into the sunny steps I made between apartment blocks on my walk home. The man was kind to me and had no reason to be. The people were kind to me and had no reason to be. I was a stranger to them, and they to me. I got back to mine. There were people sat with dogs on their laps, twine creaks under shifting seats; heat rose from the air; everything was colourful and in near-mint condition; every year has that first afternoon when the weather of last year and this is different. The cat was glad to see me; I apologised for being away. I put a Motown record on and danced around. The cat watched me do the washing-up. There was a great back-up plan for when my mood fell, but I never needed it.

I had pistachios on the brain. You see something in the same place for so many days over so many months over so many seasons, and you become affected when it is gone. I was sure to get over it. I came home and ate lunch, emptied the washing machine, I put all the groceries away. Terrible the tiredness! terrible the mood! but I was keen to overturn them. I took a mop to my forehead. I said good-bye to the cat. It was warm. There were nerves, but I was very miserable of being so silly alone. The day was wonderful and everything was clear, in a plush haze; during my teenage years I would have become tumescent, in my late thirties I was alive and it was, at best, enough. The store was busy and I looked at the stock. An employee asked me if I was okay, and I told them I was. Not two minutes later I asked how I might join one of the card games. They played with their feet, then stared out over the tables and ruckus of various games going on. They approached one table after another, explaining things. The occupying players turned and regarded me. Finally they came back—‘That lot over there can get you into a game. They’re just shifting things around.’ I stood by them and said my name aloud. They said hello and asked me some questions, friendly before a tabletop of cards that made some sort of sense. One of the men stood up and took me to a nearby table, assuring that it was no bother, and we set up for a match. His hand swooped and pointed, a new vocabulary flowing from his tongue, a bright enthusiasm.

Two hours later, I left with a tremendous sense of optimism and friendliness, an unfamiliar duet putting flourishes into the sunny steps I made between apartment blocks on my walk home. The man was kind to me and had no reason to be. The people were kind to me and had no reason to be. I was a stranger to them, and they to me. I got back to mine. There were people sat with dogs on their laps, twine creaks under shifting seats; heat rose from the air; everything was colourful and in near-mint condition; every year has that first afternoon when the weather of last year and this is different. The cat was glad to see me; I apologised for being away. I put a Motown record on and danced around. The cat watched me do the washing-up. There was a great back-up plan for when my mood fell, but I never needed it.