Jungschwäne Cygnet Cobs

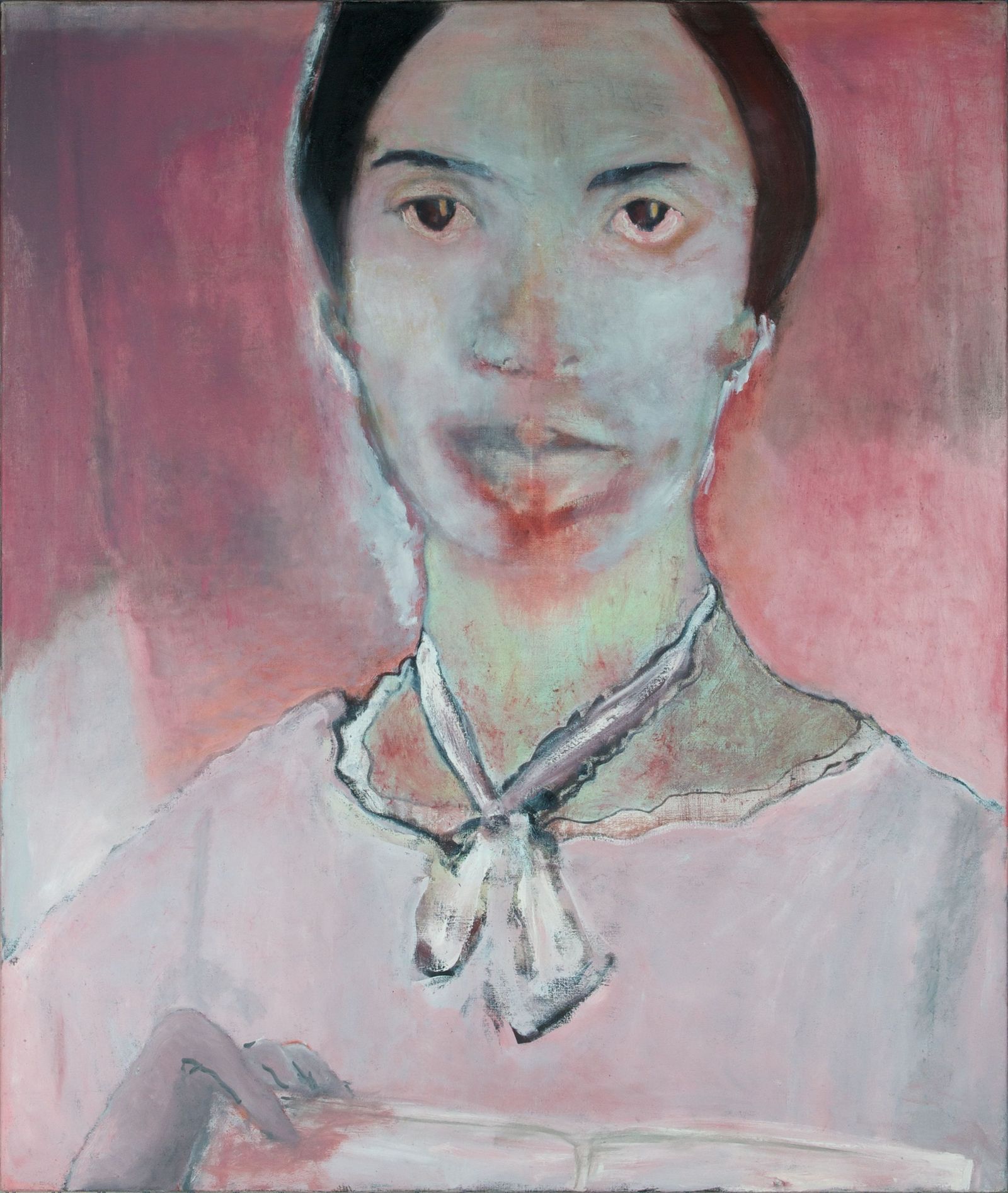

Nani

The anxiety is overwhelming, and it never abates.

All around there are birds. Often they are the only movement in a still summer day when the weather smothers you. The Chelmer does not creep or flow, it neither rushes nor swims, but wallows beneath the willows, its weeds erect and unfluttering under a mirror. Across the way, on the building opposite, a finch can be seen to swoop like handwriting onto the edge of the roof, tap its tail feathers, bulge its chest gallantly and, only a pip amongst the scenery, it dives on again; a master of the firmament.

Gulls are beautiful from a distance – their gradient plumage, wingspan, gliding without effort, almighty and large – until one comes close: their beady yellow eyes and calls, boldness, greed, territorial and violent to boot. Below them and their scuffling, their angry chases, is a family of swans nestled in the river’s bend. They do not mind when humans come to observe their chicks, for they coo and respect space. The swans – her majesty’s swans, apparently – do not become flustered or angry. The swan’s neck rifles under the water, bent at its surface. It sniffs something out. The grey balls of cygnet watch on. It is a lesson. It is grace, even in education.

A headteacher moved around an empty carpark next to a vacant building that would soon become her school. More accurately, the school would belong to a well-spoken man with three shirt buttons undone and wearing Chelsea boots, but he was on the phone with his heel up on a wall, saying—‘Yah’ and ‘Yah’ over and over to the other side. It was a hot day in West London. Affluent residents passed by on bicycles, in large chauffeurdriven 4x4 vehicles, walking dogs with fine carriage, coats shining as they panted by ankles and halt at the road edge. If I was not needed for conference, then I gazed up at the houses around and decided which I would take, had I the choice. The headteacher took a moment between professional conversations to engage with the architect, asking where in Australia he was from. When he responded, she made some vague accusations to his character with a giggle, which he denied. There were words scrawled in green ink upon his left hand. The headteacher was young, tall, her blonde hair pulled back and scrawled with greys. She was like no headteacher I had ever known. My English teacher in secondary school, Ms Harold, was an east coast Australian, and it was she who ignited my romance for the written word.

My anxiety is overwhelming, it haunts and taunts me, never abates.

All around there are birds. Often they are the only movement in a still summer day when the weather smothers you. The Chelmer does not creep or flow, it neither rushes nor swims, but wallows beneath the willows, its weeds erect and unfluttering under a mirror. Across the way, on the building opposite, a finch can be seen to swoop like handwriting onto the edge of the roof, tap its tail feathers, bulge its chest gallantly and, only a pip amongst the scenery, it dives on again; a master of the firmament.

Gulls are beautiful from a distance – their gradient plumage, wingspan, gliding without effort, almighty and large – until one comes close: their beady yellow eyes and calls, boldness, greed, territorial and violent to boot. Below them and their scuffling, their angry chases, is a family of swans nestled in the river’s bend. They do not mind when humans come to observe their chicks, for they coo and respect space. The swans – her majesty’s swans, apparently – do not become flustered or angry. The swan’s neck rifles under the water, bent at its surface. It sniffs something out. The grey balls of cygnet watch on. It is a lesson. It is grace, even in education.

A headteacher moved around an empty carpark next to a vacant building that would soon become her school. More accurately, the school would belong to a well-spoken man with three shirt buttons undone and wearing Chelsea boots, but he was on the phone with his heel up on a wall, saying—‘Yah’ and ‘Yah’ over and over to the other side. It was a hot day in West London. Affluent residents passed by on bicycles, in large chauffeurdriven 4x4 vehicles, walking dogs with fine carriage, coats shining as they panted by ankles and halt at the road edge. If I was not needed for conference, then I gazed up at the houses around and decided which I would take, had I the choice. The headteacher took a moment between professional conversations to engage with the architect, asking where in Australia he was from. When he responded, she made some vague accusations to his character with a giggle, which he denied. There were words scrawled in green ink upon his left hand. The headteacher was young, tall, her blonde hair pulled back and scrawled with greys. She was like no headteacher I had ever known. My English teacher in secondary school, Ms Harold, was an east coast Australian, and it was she who ignited my romance for the written word.

My anxiety is overwhelming, it haunts and taunts me, never abates.

Every late spring at my parents, swallows return. They

nest up in the eaves at the back of the house. It is regular as a calendar, and

my father enjoys it immensely, rubbing his hands about the patio. They fly so

fast that it is easy for one to lose sight of them. All that can be made out is

their piercing tweets as they scour for insects. They rush past one’s ear; the

draught and the sound. Their silhouettes, cut with a stanley knife, prick the

orange sky, swept quick in the ovals of a quiet neighbourhood against open

windows and English hands fanning. How envious I am of their migration! Standing

there, I am pulled to northern Africa and then central Europe, back &

forth, an annual pendulum, a great flock moving as one, chasing sunshine. At

last, in the final moment, I break free of them all, and I grace outwards into

a speck. The flock moves on. I cannot be seen. I am away and alone.

Ms Harold’s classroom, I remember it all in winter. The closing afternoons to darkness. The light never had much lustre, but it faded out along the height of the busstop, where Franklin bullied me before the fifteen-fifty-eight, until one day I pulled a pair of compasses from my pocket. It was too much of nuisance, he said, for it to land in his thigh, and he never troubled me again. There was no sense of accomplishment; instead, I walked to another busstop, one where no other students waited.

Any city in summer is magnificent, but I, like Woolf, know only London as much as I would wish to know any city. Yes, certain parts of London look sublime when frowning in sheets of drizzle, but summer is such a joy! On the Circle Line, I watched it get busier as we went westward. There were labourers and officeworkers, there were tourists, schoolchildren. Everyone freckled with sweat, everyone swaying together in a chubby line as though in a dancehall. A lady held safely a large, framed print of Blake. Such a sight I missed; nowhere else, other than London, seemed to possess, with any degree of frequency, a middleaged lady carrying a large, framed print by Blake. It was not so much to her; she balanced it on the toe of her sandals, against one of the central bars of the car. I am only so much of a Londoner (no longer) that I find the toing and froing of the public steel a source of comfort. Perhaps it is too long I have been away. Perhaps that ghastly city made me feel like I was in love when I was not. Perhaps the further I sank into it, the more enchanted I became. Either way, I had missed it, and I realised the fact at that exact moment.

Ms Harold’s classroom, I remember it all in winter. The closing afternoons to darkness. The light never had much lustre, but it faded out along the height of the busstop, where Franklin bullied me before the fifteen-fifty-eight, until one day I pulled a pair of compasses from my pocket. It was too much of nuisance, he said, for it to land in his thigh, and he never troubled me again. There was no sense of accomplishment; instead, I walked to another busstop, one where no other students waited.

Any city in summer is magnificent, but I, like Woolf, know only London as much as I would wish to know any city. Yes, certain parts of London look sublime when frowning in sheets of drizzle, but summer is such a joy! On the Circle Line, I watched it get busier as we went westward. There were labourers and officeworkers, there were tourists, schoolchildren. Everyone freckled with sweat, everyone swaying together in a chubby line as though in a dancehall. A lady held safely a large, framed print of Blake. Such a sight I missed; nowhere else, other than London, seemed to possess, with any degree of frequency, a middleaged lady carrying a large, framed print by Blake. It was not so much to her; she balanced it on the toe of her sandals, against one of the central bars of the car. I am only so much of a Londoner (no longer) that I find the toing and froing of the public steel a source of comfort. Perhaps it is too long I have been away. Perhaps that ghastly city made me feel like I was in love when I was not. Perhaps the further I sank into it, the more enchanted I became. Either way, I had missed it, and I realised the fact at that exact moment.

Nowadays I hear voices or sounds that are not there.

It is all gradual. The mind is not some house of cards, but a coastline, seemingly

solid, yes, until it is steadily worn away by the pounding waves of existence!

I walked home from the station, listening to music (Clean feat. Liv.e by

Pink Siifu & Fly Anakin) and turned to confront a man at my shoulder, but

he was not there. He followed me. I turned again to address this pestering

stranger, but there was no such presence, and I was baffled. It must be the

music, I thought, yes, the music. And I walked on. Every time I heard the voices

again, I ignored them, calmed myself down, and walked on. I hear voices when I

am in bed, when I am washing up, when I am doing nothing but trying to look out

peacefully.

The day had been all over the place. And I was glad to be back. Every step I took closer to my apartment was as though I shed a weight from my shoulders. The lift took me up and I emerged, excusing myself past someone waiting, casually wishing him hello. I put my key to the lock and it did not click. I had not locked it! How foolish! I had been in such a rush to attend the meeting on the farside of London, that I had forgotten to lock my own front door! Instantly I became uneasy. I turned the knob and walked inside, but it stuck! They had engaged the lockchain! My heart began to thump. Every organ that I had carried around so carelessly before immediately started to weigh upon my skeleton! I shoved the door against the chain once more. Should I call out, try to bargain with them? They could not pass without harassing me, as I had caught them in the act. Was it worse? Would I prefer to return to a looted flat, empty, and deal with the aftermath? Or could I challenge these strangers and implore them to drop my belongings? Already it was too late; their very presence had besmirched my sense of security and no longer would I feel safe within the confines of my home. With my right hand, I prepared myself for conflict. I shoved once more against my front door.

Then I looked down and I looked around.

The books that climbed up the walls of my hallway were not there; nor were the prints of Ellen Rogers, Georgia O’Keeffe, Marlene Dumas or Yves Klein. Even the floor was not the same, and the slippers positioned between the gap of this quarter-opened door were not my own. In fact, not a single furnishing or adornment belonged to me.

The day had been all over the place. And I was glad to be back. Every step I took closer to my apartment was as though I shed a weight from my shoulders. The lift took me up and I emerged, excusing myself past someone waiting, casually wishing him hello. I put my key to the lock and it did not click. I had not locked it! How foolish! I had been in such a rush to attend the meeting on the farside of London, that I had forgotten to lock my own front door! Instantly I became uneasy. I turned the knob and walked inside, but it stuck! They had engaged the lockchain! My heart began to thump. Every organ that I had carried around so carelessly before immediately started to weigh upon my skeleton! I shoved the door against the chain once more. Should I call out, try to bargain with them? They could not pass without harassing me, as I had caught them in the act. Was it worse? Would I prefer to return to a looted flat, empty, and deal with the aftermath? Or could I challenge these strangers and implore them to drop my belongings? Already it was too late; their very presence had besmirched my sense of security and no longer would I feel safe within the confines of my home. With my right hand, I prepared myself for conflict. I shoved once more against my front door.

Then I looked down and I looked around.

The books that climbed up the walls of my hallway were not there; nor were the prints of Ellen Rogers, Georgia O’Keeffe, Marlene Dumas or Yves Klein. Even the floor was not the same, and the slippers positioned between the gap of this quarter-opened door were not my own. In fact, not a single furnishing or adornment belonged to me.

It was at that moment I stepped backwards and saw the

metal numbers screwed into wood were not my own. My own number was higher, by

an entire floor and I gasped. For a second I thought to cry out an apology, but

it became stuck in my throat, which trembled to fulfil its breath. I retreated

in terror. I hurried away, and when I got back to my true hallway, I collapsed

in a heap on the chair I keep there.

The anxiety is overwhelming, and I make it worse.

Sometimes I try to make the anxiety worse, to push myself. These are the hobbies of one who possibly losing their mind, or trying to reclaim it. Pessoa, Van Gogh, Celine all walked the same path.

I sought to calm myself down, so I washed my glasses – day glasses, juice glasses, wine glasses, work flask, ash tray – and felt less frayed. I would get through the evening. I cooked myself a splendid meal of smoked basa and spinach mash, then I sat in my armchair diagonally, chainsmoking and taking looks out at the gulls that were still quite restless.

A shower would put an end to the day. It would ready me for the solitude of bed. Each layer of perspiration fell off me like a stagecurtain, down to the curves of a tub, and then out out out, away. As I stood washing the detergent off my doughy frame, I thought I heard someone smash at the front door thrice. It is only a figment of your imagination, I thought, I told myself. My testicles withdrew. No, the knocks had happened, for they rippled up through my property and bathtub to the bones of my legs. Carefully, I towelled off and held my breath. Were they still there? I had to pass the front door to reach my clothes, as I was naked and in no condition to address another person. It was strange that, out of everything, I was most aware that my genitalia had shrunk beyond all belief – at least in sensation – and I knew that I was not quite so much a man. Soon the stranger would knock again, they would force down my door. What could I do to stop them? Please let alone the plants from my mother and aunt. I sat in my armchair, tapping the last of my tobacco pouch until there was the extent of silence I craved.

My frame was paper, soaked and fragile from the blood that ran around it. In bed, I listened out. There was nothing. I knew that there was nothing, until there was nothing, only the parade of dream, pulling me along for the ride, fragments of everyday presented like episodes of a TV show, nonsensical

The anxiety is overwhelming, and I make it worse.

Sometimes I try to make the anxiety worse, to push myself. These are the hobbies of one who possibly losing their mind, or trying to reclaim it. Pessoa, Van Gogh, Celine all walked the same path.

I sought to calm myself down, so I washed my glasses – day glasses, juice glasses, wine glasses, work flask, ash tray – and felt less frayed. I would get through the evening. I cooked myself a splendid meal of smoked basa and spinach mash, then I sat in my armchair diagonally, chainsmoking and taking looks out at the gulls that were still quite restless.

A shower would put an end to the day. It would ready me for the solitude of bed. Each layer of perspiration fell off me like a stagecurtain, down to the curves of a tub, and then out out out, away. As I stood washing the detergent off my doughy frame, I thought I heard someone smash at the front door thrice. It is only a figment of your imagination, I thought, I told myself. My testicles withdrew. No, the knocks had happened, for they rippled up through my property and bathtub to the bones of my legs. Carefully, I towelled off and held my breath. Were they still there? I had to pass the front door to reach my clothes, as I was naked and in no condition to address another person. It was strange that, out of everything, I was most aware that my genitalia had shrunk beyond all belief – at least in sensation – and I knew that I was not quite so much a man. Soon the stranger would knock again, they would force down my door. What could I do to stop them? Please let alone the plants from my mother and aunt. I sat in my armchair, tapping the last of my tobacco pouch until there was the extent of silence I craved.

My frame was paper, soaked and fragile from the blood that ran around it. In bed, I listened out. There was nothing. I knew that there was nothing, until there was nothing, only the parade of dream, pulling me along for the ride, fragments of everyday presented like episodes of a TV show, nonsensical