Hands’ Ending

I

They had been communicating regularly over the Christmas holiday, that first trip back home three months into university, when one – at least in his case – is shocked to discover how poorly they have managed their money and how drastically their sleep pattern has changed. At late hours, they would find themselves the last remaining awake in their households, dissatisfied with the silence, and so would reach out to each other.

‘I got a camera phone,’ he tells her when she asks, at one in the boxing day morning, what presents he received.

‘Send me a photo of your hands,’ she says.

‘Why?’ says he.

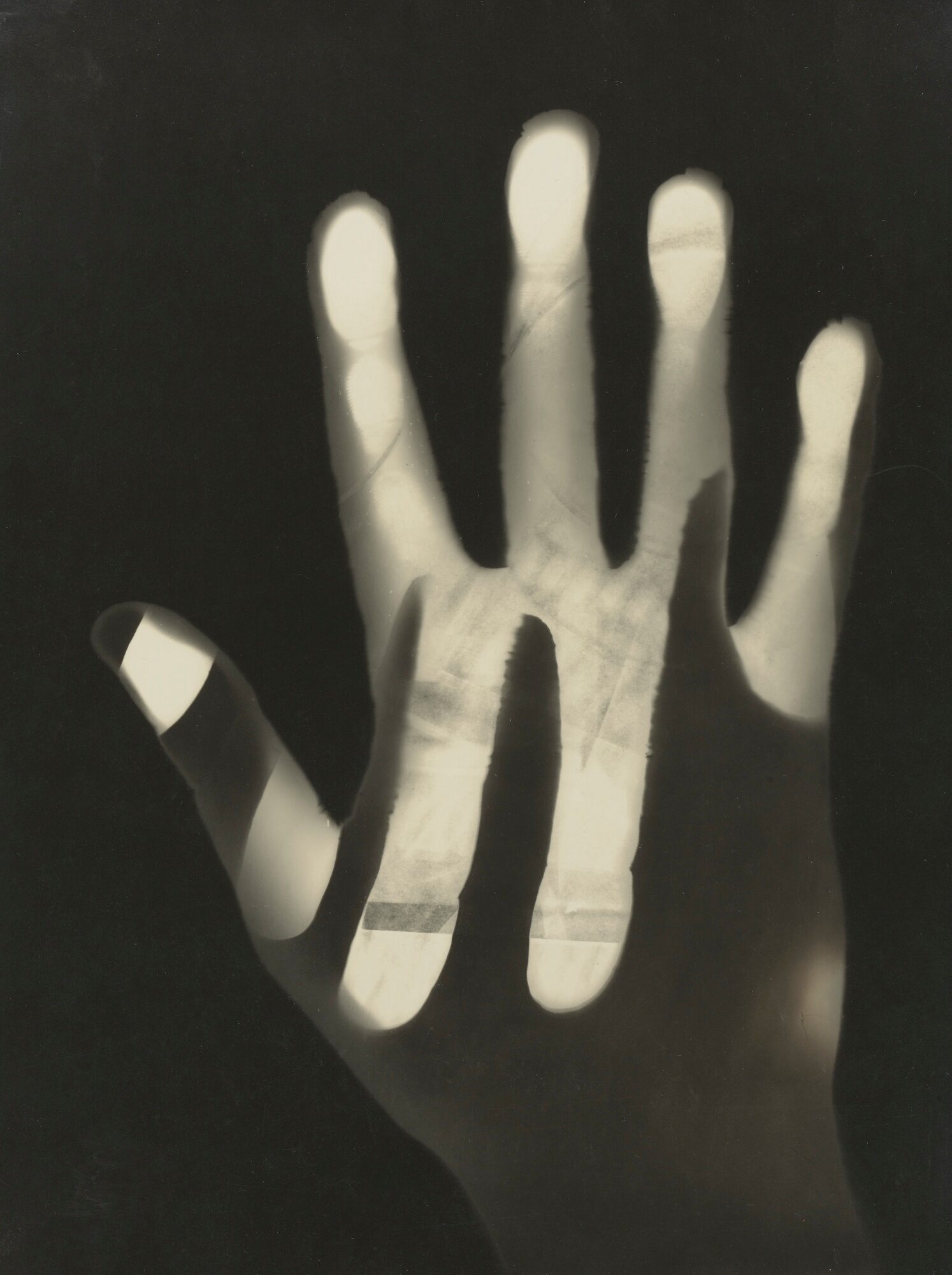

The light in his bedroom is poor, and the camera makes everything dimmer, so he goes, compliantly, to the bathroom, and takes a photograph with his new camera phone of his left hand. The composition is off, the hand placed in the middle of the frame, stretched out, unremarkable, but well-lit; lit well enough to catch the pink tint of cold winter’s flush. ‘There you go!’ He waits a couple of moments—

‘Send me another one, please. But just relax your hand.’

He is not sure how to relax his hand now that he has been asked to do so, nor from what angle a relaxed hand should be captured. He does his best, acutely aware that he is standing in the bathroom without using any of its facilities, although its fluorescent white lights are, at that late hour, making him feel more awake than he would wish. When she does not respond, he returns to his room, back beside the dim lamp, the novel he picked up in the shopping centre just before they broke up. She must have fallen asleep, he thinks and settles down to read some more, still not tired. It is no more than ten minutes before she responds—‘Lovely!’ And he asks what took her so long; he always waited impatiently for her messages. ‘I just came to your hands. Don’t tell anyone.’ He smiles. For the rest of the holiday, he sends her photographs of his hands. He takes a photograph of his hand as he is watching television, as he is out on a walk, while he is eating dinner, he takes photographs of his hand while he is brushing his teeth and fixing his hair, while he is making French toast and while he is smoking in the garden. She looks at the little photographs on her phone and, if she is alone, she acts upon them, otherwise she waits, because she is so terribly bored at her parents. By the time they return to university in the second week of January, she has come nineteen times over twenty-five different photographs of his hands. The first night back, after everyone has gone to bed, she texts him to come to her room.

II

Between dates, which were usually from Thursday till Sunday, they would speak on the phone. Before they even met, they had spent many hours on the phone while she was holidaying in Greece with her father, cycling to the beach during the day and cooking dinner for the pair of them in the evening. Two hours apart, they would grow to know one another. Eventually the conversation led to more confessions and imaginations, both anticipating how their time together, when it came, would go. She would lead him to talking her flustered and, in her father’s empty apartment, grazed by sand and warm breezes, she came and he came and they looked forward to finally acting all of it out in person. When they got to dating, the phone calls carried on, and in the same manner. Mostly they would chat about their days and learn of one another, but frequently she would ask—‘What are you doing?’

She always masturbated next to the open window in her bedroom. It was a sash window and during the summer months it was seldom shut, forever permitting sounds of the street to fill her room, which she found a comfort in, like those who put the radio or television on when they are in bed. They talked, each describing what they wish they were doing, until soft moans overcame them. With the phones to their ears, held there by a pillow, they spurred each other on with pants and gasps until one would say—‘Now,’ in the littlest voice.

When she was away on business in New York, they would speak on the phone then, too, albeit with a larger time difference and more organisation required. She showed him her room and bathrobe and she showed him her bed where she lay with jetlag, not looking forward to her professional obligations but cheered enormously by the occasion and the new blue light that was lining through the hotel’s heavy curtains. After she was showered, she called him back and asked if he missed her. He did not lie, he said yes, but he also liked to romance someone who went on business trips to Paris and New York. He told her that the bruise had bloomed on his chest, next to his nipple, and she asked to see. He did so, pointing. ‘I’m so happy I like your hands.’ He asked her what she meant as she lied down on an unmade bed. ‘I like your hands,’ like it was the most normal compliment. He told her he was happy she liked his hands. ‘And I think hands mirror the willy. So I think it’s like yours.’ He asked her what she meant as she undid her dressing gown. ‘Like, the shape of the hands often is a bit similar to the man’s penis. So because I like the look of your hands…’

III

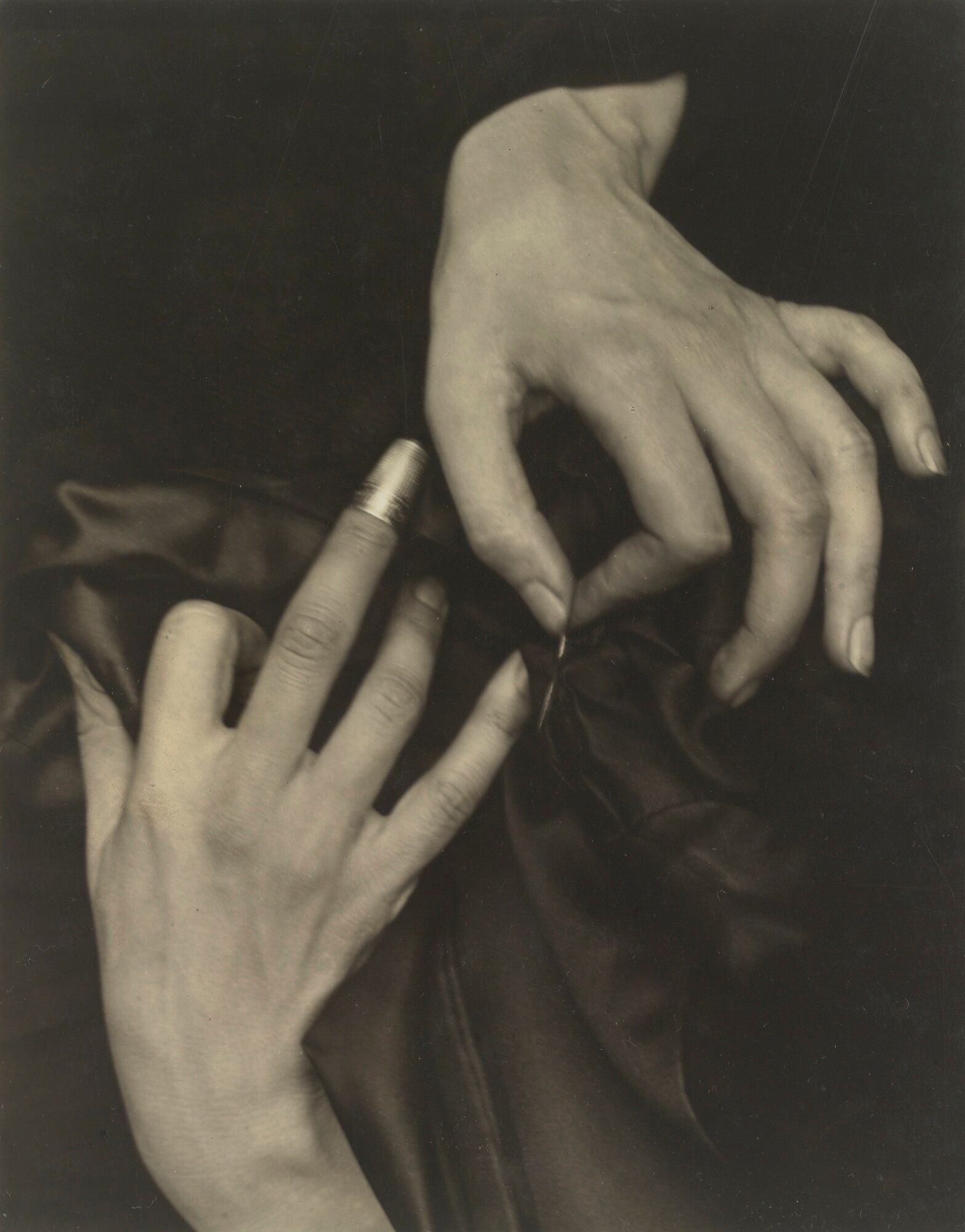

There is a whole website dedicated to photographs of her hands; polaroids of her reaching for various objects – mostly flowers & plants – right there for everybody to see. She notes the camera used and the location of all the polaroids: Netherlands, Germany, Spain, Czech Republic, United Kingdom. Who knows how much time passed between each, but the same hand, always the left, the clumsier but more tactile of the two, gesturing in natural light. Squares & squares & squares of seventies instant photography.

He scrolls through them, trying to determine why these, of all those taken, were chosen for the website. They are all quite different, yes, but more than that, they stir something within him that he can neither understand nor deny; and so he succumbs to each, absorbing them and staring without blinking. Is there another archive somewhere, in the possession of someone obsessed, that includes this huge a portrayal of one person’s left hand? A right-handed person’s left hand is weaker, but their left leg is stronger, better balanced, a muscular pivot if needed. He looks at her left hand and imagines her left leg, the muscles that entwine and grip along its length. He notes, with unusual interest, the tendons that accentuate as she splays her fingers in the tendrils of a tumbling houseplant; they were something he had never paid particular attention to before, those tendons that fan from the tenderest of wrists out towards the slim elegance of her four long digits and thin thumb. The jewellery is different in each, with some consistencies. There is a ring on her index finger that makes many an appearance, but in others it is absent. Her pinky is the least adorned, followed closely by the middle finger. Are they related, he wonders, to a period in her life and what does it all mean? Does she remove them when she goes swimming or showers or goes through airport security? There is a polaroid of her petting a cat in Singapore. There is a polaroid of her grasping a can of beer. In some she is wearing nail varnish, but very few. What inspires her to wear nail varnish from one day to the next? The polaroids with nail varnish have an even greater effect on him. He does not understand. What in the shape & structure of a hand is so appealing and why should it only strike him now fully that he become aroused from it? Perhaps it is only her hand above all others. He remembers past relationships and the feature of the Her that stands out in each. This stranger has superlative hands, and so all her former lovers must remember her hands over everything else. Do they go to bed and dream of her hands? After a moment, his back arches and he puts a hand over his Christmas-with-the-family mouth to keep from waking anyone. Afterwards, breathing deeply, her hands look as good as ever.