Fourteen & A Half Years

‘Maybe you shouldn’t read that. We should avoid things that affect our mood negatively.’ She was right. Many times, while talking, I became choked up on my own words. Times have been ghastly, and she had been on holiday; sounded surprised when I asked how her break had been. The thing is: I actually cared; I hope by now she knows that when I ask a question I care about the answer. Afterwards, I sat back down to work. As though I were about to weep, I went for a walk – ‘Really?’ – and it was quiet out, but for dog-owners who had spent the day working, and the tender old women who lived only to love their dogs and walk them whenever they wanted, holding leads like lovers hold hands, and so heartwarming to see when they rested on a wooden bench, and lifted the pup into their lap. That evening my brother was visiting his girlfriend, so I had the house to myself. Too tired to write, too sad to write, too vacant to do anything but – I sat down and played video games. Afterwards I realised it had been many days since I had enjoyed my sex, although already it was late. My body reacted quickly, starved. How miserable I had been – and nothing but! – that I had forgotten to enjoy the larger pleasures of my small body. No sooner had my hand wandered than my body tensed itself to the touch. When sadness is so overwhelming, and privacy rare, one tends to forego or forget particular things. It was late when I finished breathless in the darkness, dropping my phone’s only light next to me and staring at the ceiling.

My name was being said in a dream through which I was running—‘It’s 07:05. Aren’t you in the office today?’ My mother stood at my bedroom door; must have slept through the alarm. In an instant, I sat up, tossed the sheets off me and got my towel. The meeting at nine would be missed. The train at 08:05 is mostly populated by young people on their way to college. That used to be me, but back then it left at 08:18. Although it is perhaps boring, the gradual shift of train timetables – minute by minute, year after year – is curiously interesting to me. That it should alter thirteen minutes over nineteen years is noteworthy enough to me that I should put it down here, as a matter of public record.

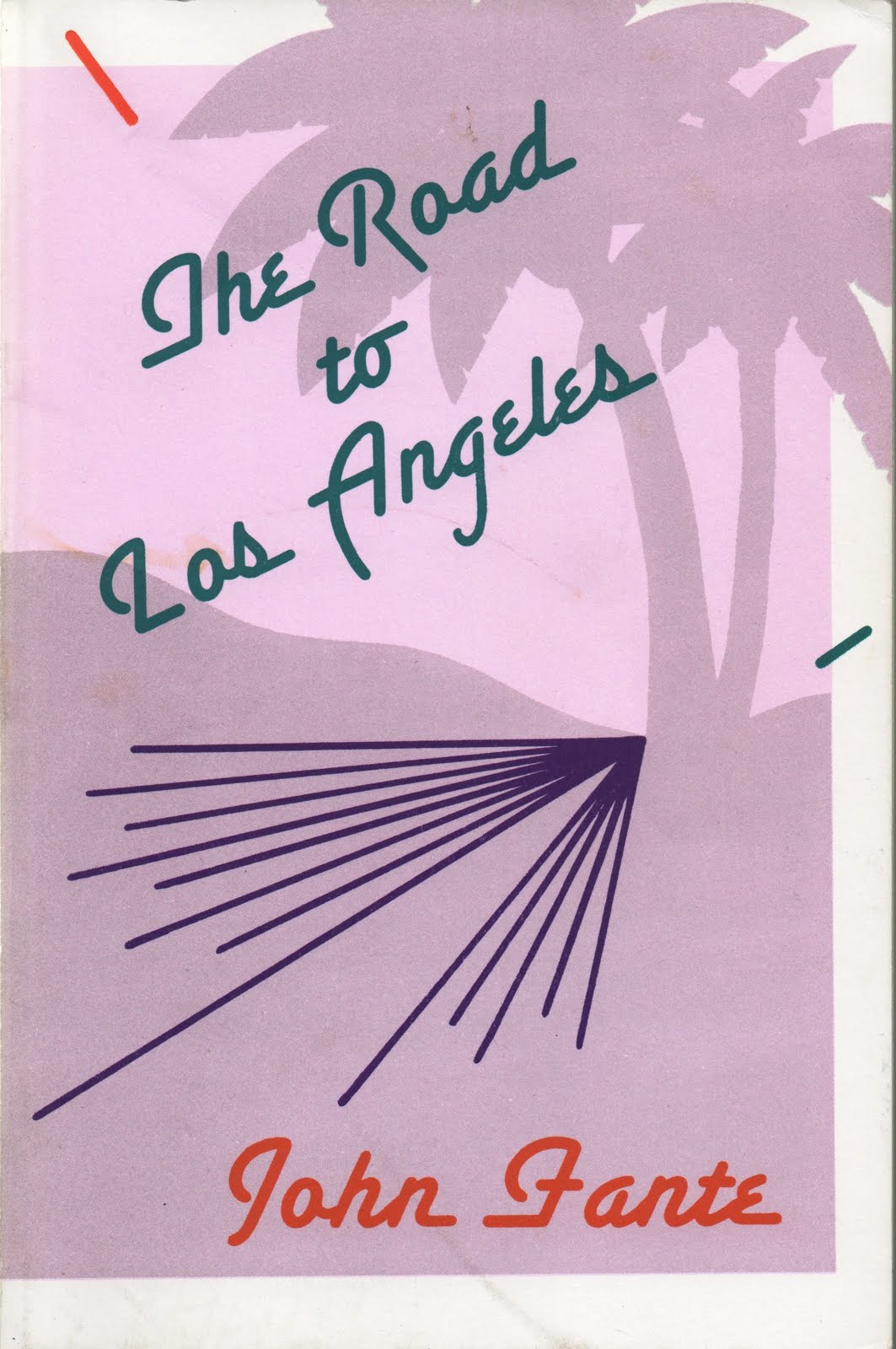

Just before leaving, I remembered what she had said about my reading material. Dashing upstairs I picked up one of my favourite books. Around the spare room of my parents’ house I have slept in for the past thirteen months, there are numerous piles of books; the books are stacked four-deep in the wardrobe, underneath the chaise longue, on a large bookshelf, atop the large bookshelf, in huge see-through plastic boxes; no longer organised, they are a mess. Why, last weekend I was desperate to read a certain book (The Waves), spent ages looking for it, only to come out tired and bookless. I knew where my favourite book was. I bought it in a terrible shopping centre while I was at university, after my favourite writer at the time recommended him. It is the book I have read the most, its pages falling out, I have kissed its chapters and slept next to it, laughed and cried at the sentences that sing from within. I took the 749 pages downstairs, pulled out Applebaum’s tome on gulags, and stuck this perfect lump in there with my bottled water and headphones.

It was another beautiful spring morning, magnificent sunshine and only the bluest ghost of winter in the air, nipping at one’s earlobes and the soft skin of clavicle’s basin (sternal notch); furiously the heaters on the train belched out an unavoidable plume of hot, heaters that in the coldest months are never switched on. The sun landed all over me in thick rectangles, warped and rotating. My friend was waiting for me at my desk when I arrived, highlighter in hand, picking breakfast out of his broken teeth with an unfurled paperclip. Whenever I ask how he is—‘Living the dream,’ he says—‘Living the fucking dream.’ I miss drinking with him, miss rolling cigarettes for him. (He has been on fifty percent pay for a year, his wife – also working for the company – not being paid at all. I asked her how they survive; she said another mortgage on their house.) After a time, I start to moan at him—‘Listen to me – when you’re not even being paid!’ I shut myself down, beginning to cry, I can feel it. He just shakes his head. He says very little, and what he does say is so quiet that it is lost amongst the sound of fan coil units and printers run out of magenta. It is so quiet there, and I am burrowed into my work, that eventually a sound pierces the silence: one of the directors is scolding a young employee. ‘Get off your phone. Every time I look up I see you on your phone.’ The young employee argues—‘I’m waiting for the computer to finish! Look!’ ‘Don’t! Don’t talk back to me!’ ‘But, Paul, look! I can’t do anything, it’s working—’ ‘Don’t talk back to me!’ I look up at my mate, who is whistling a Monty Python song and already staring back—‘Fuck this place,’ I say, and pushing my pen too hard into the paper.

He tells me the weather application on his phone is not quite reliable, but that the rain is not due for another couple of hours. By the time the lift has taken me from fifth to ground, the sky is raining. I step out into it, gladly. There are a pair of children playing by the church. There is no one else about. I walk in large circles. It is the heaven and hell of repetition. The afternoon passes without incident; only the hollow, mute soundtrack of an office, each employee sat far enough apart so as to not chatter, each too miserable to laugh, a director in the centre, his bagged grey eyes piercing left & right.

Seated outside the toilet on my train home, where the drunks who spent the day in London queue, dressed and perfumed. It was good to get back to my book. Every time someone walks to the toilet, they knock my shoulder, jolting me out the sentence. I was rushing through the pages, almost reciting them by heart. The metal frame around the window has collected a black scum of dust over the years that has never been cleaned, and a dimple in my skull that fits it like a cog, preventing my head from drooping. When I get home, my parents are sober, my brother is in the shower. I sit on the sofa, waiting, because I am so keen to wash all the muck off me. My mother & father approach ask me what is wrong, and I tell all. We speak for the duration of my tinned pint. They say— ‘Then quit.’ I listen because, again, I am too close to crying and they are sober. Oft I will ignore them – or not say a thing – when they are drunk, but their sobriety gives me pause for thought. ‘I need a drink,’ says my mother. As my father is pulling a bottle from the fridge, she says—‘Do it, darling, fuck up their weekend.’ I smile. I decide that I will quit my job because I can no longer take it.

Once upon a time I would finish work and not give it a single thought for the rest of the day, but for the past several months I go to bed thinking about it, worrying; I go for walks and cannot shift it from my thoughts; in the middle of the night I wake with nightmares and in the morning I breathe a sigh of relief when I realise that it was only a dream. ‘I look and see the people around me, colleagues and friends,’ I tell her, ‘and I don’t want to be like them.’ The spring is so pretty, my favourite of all the seasons. ‘It’s the incremental bullshit, y’know? You give an inch, then another, and soon it’s the whole mile, or whatever the saying is.’ The birds are really loud lately, and on the grass verge down the promenade I see rabbits again, invisible but for their white rears bouncing at my appearance. ‘I can’t handle it anymore.’ Everything blossoms at slightly different times. There are leaves once more. Some trees are lazy, sleeping in. They stagger, they swell like a floral symphony. ‘And the bosses’ll say I’m weak for quitting, that I couldn’t handle it – I know, I’ve been there years, I’ve heard them say it about others – but fuck that. I ain’t a mug. I need to get out of there.’

In the shower, hot water running over my face and melting away the grease of existence, I smiled and decided that I would quit my job.

Put on some clean clothes, and went into the garden to cool down, to collect myself and attempt to make sense of the worries inside my mind. When I came back in, my mother was skinning a platter of cod fillets. She held the knife just so, and was regularly sipping from her glass of wine.

‘Feeling better?’

‘Yeah, feel better for talking,’ I put something into the recycling bin so that it could be mushed up and made into something else—‘and for the support of my parents.’

She smiled, put an empty blister of ibuprofen in the bin—‘Who are they, then?’

‘I dunno but I’d love to get my hands on the bastards.’

The next day seemed like a fine day to quit my job. There was lots to do. One member of my team – friend and manager – was on holiday (moving into a house with his girlfriend) and the other outright refused to work, so it was just me. Once I had completed and issued all of our responsibilities, the architect e-mailed to inform the deadline had been put back a week. My dearest friend at the company text me that he had just handed his notice in. Things were surely crumbling. I went for a walk in the beautiful sunshine, came back, made a pot of coffee, carried out a few more tasks and then wrote to my director—

‘Please accept this letter as formal notice of my resignation from the position of senior mechanical engineer at –. My last day of employment will be 16th July 2021, as per my obligations under the terms of my employment contract.

‘I have learned a lot during my time at the company, and appreciate the opportunities and experience it has brought me, however I feel it is time to move on.

‘On a personal level, I thank you for the time you have spent tutoring and mentoring me throughout the years, as well as the time out of work enjoyed in your company. I am truly thankful.

‘I wish the company the best for the future and will of course assist in the transition period for the remainder of my contract.

‘Again, sincerest thanks.’

As I wrote, I had total conviction in what I was doing, but soon after I began doubting myself. My parents sat down behind me and commenced drinking. I read the letter to them and at the third paragraph – the only one not lifted from a template – my voice started to crack. The scale of what I was doing hit me. Fourteen and a half years. I read it to them, and when my voice faltered I pushed it harder. All the memories that flew through my uncertainty distracted me. ‘Yeah, that’s fine,’ they said.

Pointer hovering over Send. A kind of stomach that rippled within me. ‘You’re pausing, aren’t you?’ said my mother. She was goading me! A deep breath as dramatic as it was honest.

Send.

A shallower pair of lungs, a perspiration under my arms. Everything felt different. I shut down the laptop and went into the garden for a smoke. I wrote a text to my director, urging him to check his e-mails. It was such a beautiful evening. Although it was cold, it was bright and the sun, near its end, had ripened into the most vivid of colours, which it sprung upon the houses and trees all around. Some times feel like moments. The straight line flicked away from itself. I inhaled and I smiled. It was not often that I smiled at myself, and maybe I did so to reassure, but I smiled, and the cigarette tasted good, there was a fridgeful of beer, a guitar upstairs, there were the good days of mid-April, and I settled upon it that I had made a good decision.