Dover-Foxcroft, MA

Two weeks before,

the railway sent out a letter to all the residents in the vicinity of a length informing

them that they were carrying out engineering works on the railway lines during

the night, but would attempt to keep the noise down; they apologised; there was

a number you could call. At this time of year, one must sleep with the windows

open, and it was the sound of rumbling rocks knocking one another as they fell

that startled me awake, and for a brief moment I struggled to think what it was

that had stirred me prematurely one unremarkable Tuesday morning.

The air outside of the window was still. My head swung out, peering left & right. There was nothing to be seen, as much of the linear steel is hidden behind greenery that has swallowed it whole on advice from the season. Down below, though, was a police car idling in wait for someone or something; the black hips with straps and belts, padding, tools caught in the fluorescent perfume of latespring’s morning. I should poke my head out of these curtains more often, I thought, and steamed a lungful inwards. When I exited my building an hour later, the car was still idling, its engine gurgling. As is common with wretched paranoia, I hurried down the street and away from them, imagining the revs and rasp of tyres over my shoulder. Scuttling, into the dawn, there was a train to catch in nine minutes, for I had lost track of the time!

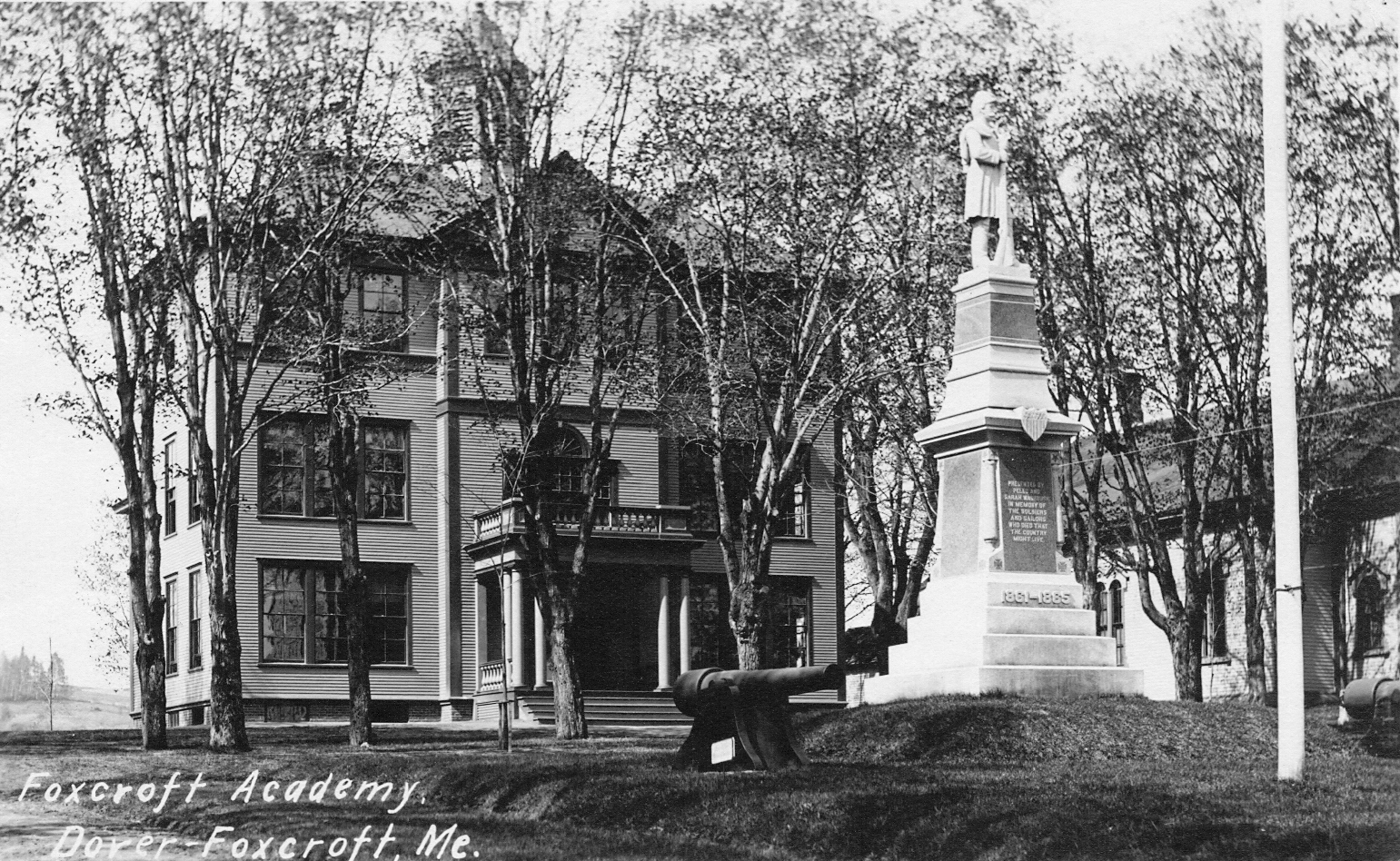

The gentleman beside my awkwardly clenched frame seemed most displeased with my having sat next to him. Videos on a phone that kept catching a reflection of the sky, small text, indeterminate. Sighing, I regarded the commuters, perhaps I might catch some sleep. Another gentleman scribbled in a notebook, no more than five words a line, his left hand crooked, curving in its flicks, the notebook vertical on his thigh. Another young gentleman was on his phone; long messages on the received side, heart emojis standing out like cities on a map. Spring is a good time to be in love. There was a gentleman, too, who I thought looked a lot like an American, the lines on his face, slicked black hair with combsteeth running through, already a light film of oil upon his face; not just any American but a car mechanic in Dover-Foxcroft, Maine, USA, the owner, affable, training his son, Lucas, over there, got him faxing out invoices before the rush; the flag outside hangs down in still ripples. There were wedding bands on every left hand. Who took these men to bed, that they recoil from me? At one point, they charmed and were charming, they invited and swooned, it is likely they held romantically her naked hand, which then came to be pricked with a band of its own, together at a ceremony.

The air outside of the window was still. My head swung out, peering left & right. There was nothing to be seen, as much of the linear steel is hidden behind greenery that has swallowed it whole on advice from the season. Down below, though, was a police car idling in wait for someone or something; the black hips with straps and belts, padding, tools caught in the fluorescent perfume of latespring’s morning. I should poke my head out of these curtains more often, I thought, and steamed a lungful inwards. When I exited my building an hour later, the car was still idling, its engine gurgling. As is common with wretched paranoia, I hurried down the street and away from them, imagining the revs and rasp of tyres over my shoulder. Scuttling, into the dawn, there was a train to catch in nine minutes, for I had lost track of the time!

The gentleman beside my awkwardly clenched frame seemed most displeased with my having sat next to him. Videos on a phone that kept catching a reflection of the sky, small text, indeterminate. Sighing, I regarded the commuters, perhaps I might catch some sleep. Another gentleman scribbled in a notebook, no more than five words a line, his left hand crooked, curving in its flicks, the notebook vertical on his thigh. Another young gentleman was on his phone; long messages on the received side, heart emojis standing out like cities on a map. Spring is a good time to be in love. There was a gentleman, too, who I thought looked a lot like an American, the lines on his face, slicked black hair with combsteeth running through, already a light film of oil upon his face; not just any American but a car mechanic in Dover-Foxcroft, Maine, USA, the owner, affable, training his son, Lucas, over there, got him faxing out invoices before the rush; the flag outside hangs down in still ripples. There were wedding bands on every left hand. Who took these men to bed, that they recoil from me? At one point, they charmed and were charming, they invited and swooned, it is likely they held romantically her naked hand, which then came to be pricked with a band of its own, together at a ceremony.

What comes out of

the city is the scent of its numerous parks as they ripened: blossom and

birdshit. Blossom sticks to the fingers if it is plucked. What drives into the

city is people, by the tubeload, they primp and swagger, groan, molest their mobile

devices, meander across the road without looking. The Prets bulge with caffeine

patience, nobody quite sure whether they are queueing or waiting. My order is

quick, but when I am down the way, to my lips—ugh, coconut milk! Stolen from

some beach or tropical plantation only for me to grimace and gag! This will surely

not be my day. Early hours in the office, blinds lowered by an overnight

phantom, and raised by one such as myself, who likes to make-believe they are a

flower.

![]()

‘This is—’ he said my name, body giving way for an introduction—‘He’s the grumpiest man you’ll ever meet.’ The intern looked at me with soft eyes. They get younger and younger while I stay the same age. I told him that I would shake his hand were it not for the fact that I was eating breakfast; he appeared to understand, but who knows. My buttery fingers were no concern of the keyboard, though, as I spun back on my chair and frantically typed out another paragraph into a report. It is important to distance oneself from interns. They are all Irish, with those trustworthy, playful accents, holed up in Bethnall Green or Shoreditch, making the most each day and evening with an enviable delight.

‘This is—’ he said my name, body giving way for an introduction—‘He’s the grumpiest man you’ll ever meet.’ The intern looked at me with soft eyes. They get younger and younger while I stay the same age. I told him that I would shake his hand were it not for the fact that I was eating breakfast; he appeared to understand, but who knows. My buttery fingers were no concern of the keyboard, though, as I spun back on my chair and frantically typed out another paragraph into a report. It is important to distance oneself from interns. They are all Irish, with those trustworthy, playful accents, holed up in Bethnall Green or Shoreditch, making the most each day and evening with an enviable delight.

At lunch I went for

a walk, and it seemed that the unluckiest phrase of a song happened as I passed

by a sushi restaurant. I welled up, almost teared, for the memories stung me on

my shoulder, a hornet of pre-covid love. And it was love! a blossom of love,

sticky between the fingers. I would walk the route over and over until it lost

all meaning. When I was making my way back, Milly was coming toward me. Should

I ignore her? She was dressed well for spring, a patterned shirt and loose

jeans that I saw around her hips and thighs. A woman’s thigh deserve to house

the biggest bone in the body, such is its splendour. I nodded hello. She called

out to me as we passed—‘Why do you look so angry?!’ It was not my

intention; only a face that relaxes. Was it me who was angry as the weather

shone? Out there was someone who could make me smile while I walked the streets

of London. Heels tap the pavement, almost hollow, worn at an angle against the

grindstone of London Wall.

It was really an unremarkable day except for the gentleman, a colleague, who insists on disturbing me during my lunchbreak, headphones on, chewing, watching some video or other about European campaigns or the Sicilian opening. He is undeterred when I ignore him, and persists, as though I were sitting there begging for conference.

It was an unremarkable day, too, when I boarded a train bound for my childhood home. On the chalkboard of my mind, I calculated the time I would arrive there, when it would not happen but would alight with me in some two-thirds town. I waited for my father outside by the bicycle rack and last-minute cigarettes. ‘You walk too fast,’ he told me—‘I can’t walk as fast as you.’ We took the same route I used to route up to my sixth form college. Men in foreign tongues leaned in the doorways of greengrocers and cornershops, they smoked, chatted in garish t-shirts, loaded baskets and smiled handsomely in the rolling sun. Commercial Rd was somewhere out there, stinging me too like a hornet; the shoplong racks of vegetables & fruit catching a tan. I was sixteen twenty years ago, and the route came at me with a ferocity that I was not best prepared for, especially as my father discussed work. ‘Hang on a minute, son, let me remove my jacket.’ As I stood by the river, watching the swell of leaves in murky depths, the trembling mirror of overhung trees.

It was really an unremarkable day except for the gentleman, a colleague, who insists on disturbing me during my lunchbreak, headphones on, chewing, watching some video or other about European campaigns or the Sicilian opening. He is undeterred when I ignore him, and persists, as though I were sitting there begging for conference.

It was an unremarkable day, too, when I boarded a train bound for my childhood home. On the chalkboard of my mind, I calculated the time I would arrive there, when it would not happen but would alight with me in some two-thirds town. I waited for my father outside by the bicycle rack and last-minute cigarettes. ‘You walk too fast,’ he told me—‘I can’t walk as fast as you.’ We took the same route I used to route up to my sixth form college. Men in foreign tongues leaned in the doorways of greengrocers and cornershops, they smoked, chatted in garish t-shirts, loaded baskets and smiled handsomely in the rolling sun. Commercial Rd was somewhere out there, stinging me too like a hornet; the shoplong racks of vegetables & fruit catching a tan. I was sixteen twenty years ago, and the route came at me with a ferocity that I was not best prepared for, especially as my father discussed work. ‘Hang on a minute, son, let me remove my jacket.’ As I stood by the river, watching the swell of leaves in murky depths, the trembling mirror of overhung trees.

We stood outside of

the theatre as a vagrant under the influence shouted in an African accent, his

collar upturned. Nonsense. I bought us a pair of beers. They were cold and

sweated. My brother and his girlfriend turned up. She embraced my father then

me—‘You don’t have to hug me every time you say hello, you know?’ She was

offended. We took our seats and the comic came out. He had gained considerable

weight during lockdown.

It was T— at university, seventeen years ago, who introduced me to him, over & over the in the DVD player, until, at last, as with all good art, something clicked. Then I was there in my hometown, anxiously yet hopefully looking around for someone I might recognise; not that we might converse, but that I could see how they had aged, whether I recognised them; would they say hello? That life of sixteen to seventeen was centuries and many flashing lights away.

There was a couple next to me, sharing a small pot of ice cream. The spoon was flat, passed between both. I clenched away from her, holding myself in. I laughed, but I do not laugh loudly. You see, I laughed with my mouth open as tears ran down my face. I picked the tears away from my cheeks, and they were sticky. During the interval, I went back outside into the crowd for a cigarette. We were next to the hole in the wall; the Hole In The Wall. It was ninety-one. My mother was in the hospital with my new brother on one of his many visits to monitor his infantile asthma, a chicken’s ribcage enlarged and deflating under duress. My father took us to see Beauty and the Beast and then, on our way to the car, we stopped at the hole in the wall, where we played and I remember the tiny bits of streetlight on the cobbles, the echoes off the wall.

The second half left me unamused. I did not laugh once, which was unsettling to me, as I was in the third row and he could clearly see me. I was gripped by something. Where had this feeling come from, that I could only sit there staring wide-eyed at a guitar pedal on the stage, at the level of my own wet eyes? Belle spun in yellow and the Beast was draped in blue; the ballroom was golden, and golden is such a different colour to yellow. I tapped my feet at the train station home, my stomach in knots, or maybe just one perfect knot. Why was I not laughing? It was cool in the carriage. It was an unremarkable Tuesday.

It was T— at university, seventeen years ago, who introduced me to him, over & over the in the DVD player, until, at last, as with all good art, something clicked. Then I was there in my hometown, anxiously yet hopefully looking around for someone I might recognise; not that we might converse, but that I could see how they had aged, whether I recognised them; would they say hello? That life of sixteen to seventeen was centuries and many flashing lights away.

There was a couple next to me, sharing a small pot of ice cream. The spoon was flat, passed between both. I clenched away from her, holding myself in. I laughed, but I do not laugh loudly. You see, I laughed with my mouth open as tears ran down my face. I picked the tears away from my cheeks, and they were sticky. During the interval, I went back outside into the crowd for a cigarette. We were next to the hole in the wall; the Hole In The Wall. It was ninety-one. My mother was in the hospital with my new brother on one of his many visits to monitor his infantile asthma, a chicken’s ribcage enlarged and deflating under duress. My father took us to see Beauty and the Beast and then, on our way to the car, we stopped at the hole in the wall, where we played and I remember the tiny bits of streetlight on the cobbles, the echoes off the wall.

The second half left me unamused. I did not laugh once, which was unsettling to me, as I was in the third row and he could clearly see me. I was gripped by something. Where had this feeling come from, that I could only sit there staring wide-eyed at a guitar pedal on the stage, at the level of my own wet eyes? Belle spun in yellow and the Beast was draped in blue; the ballroom was golden, and golden is such a different colour to yellow. I tapped my feet at the train station home, my stomach in knots, or maybe just one perfect knot. Why was I not laughing? It was cool in the carriage. It was an unremarkable Tuesday.