Dark On The Way Out, Dark On The Way In

Now it is

dark on the way out and dark on the way in. If it is a clear day, if there are

no rainclouds, then one is able to watch the sun rise over the vacant flatlands

between Great Bentley and Alresford. Wednesday’s sun rise was the most

beautiful its spectators had witnessed in recent memory, and one passenger—in

the third carriage from the back—was reduced to tears, trying to pull himself

together, for it was a sight that caught him tired and raw and he thought that

the planet could really be such a beautiful place as, over the marshes of

Wivenhoe, a thick mist swam in whitest white over the muddy banks of the river

and between the resting cows and their moving jaws. Then the rain finally fell

and a rainbow rolled therein, its spectrum towering over the redbrick walls of

the empty warehouses down by the quayside. The tears slowly soaked into his

mask and sleep came.

My Thursday night has cancelled, she said. Could I do then, she said. ‘That’ll work,’ I said. Thursday morning I trimmed my beard and took some toiletries to work, where I passed the day in a kind of nervous excitement. Half-six, she said, in Farringdon. My reflection in the elevator mirror pressed back against me.

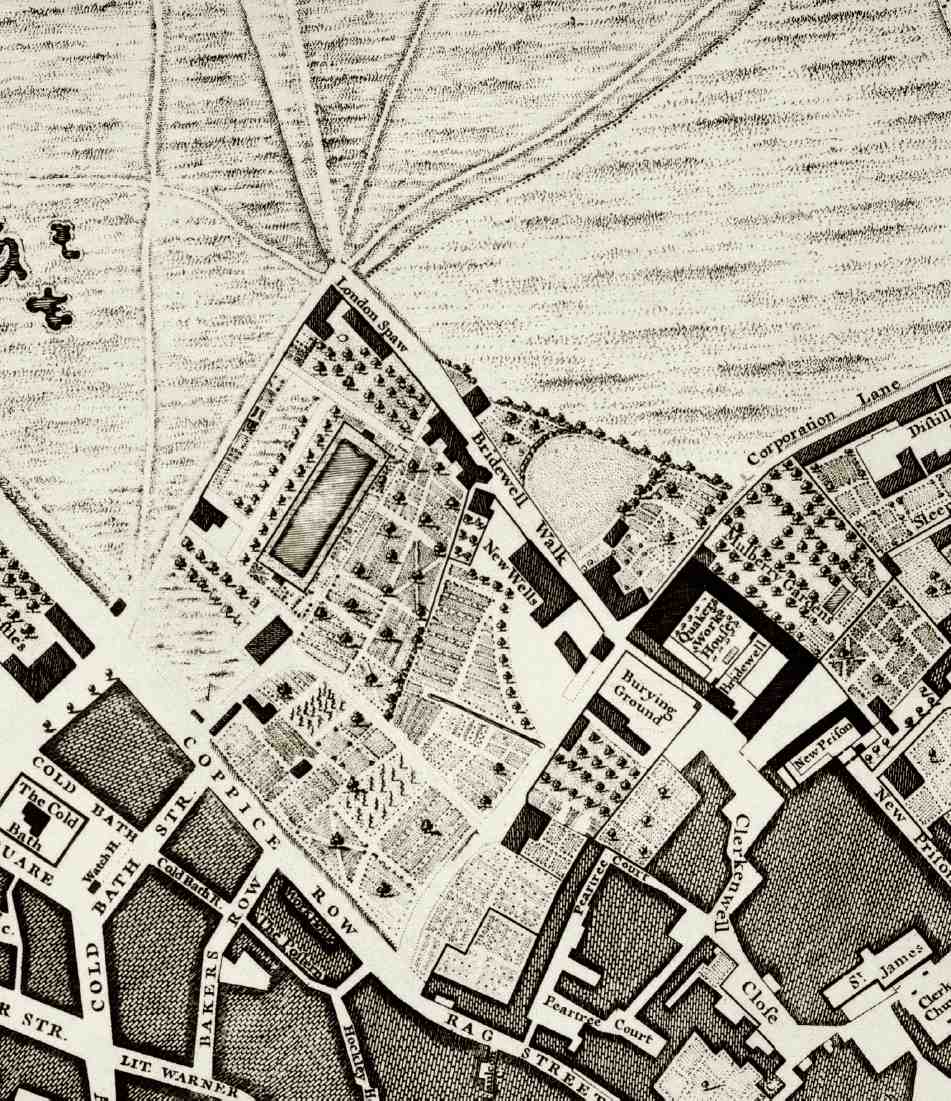

Rather walk than take the tube. Halfway, I was captured by a desire to keep on walking, past St Bartholomew’s hospital, along Chancery Lane, straight through Shaftesbury Avenue, passing by the millionaire townhouses then clear out the western suburbs and into the counties. It was not that I found myself unwilling to attend my engagement, but what could be finer than to walk and to carry on walking? Being in motion through nothing but my own limbs and wornout shoes! For so long I had traipsed the same old routes but here, in front of me, was a new one! People were walking one way and I was going another. I did venture down a road I had not been down before. It was a quiet road, with empty buildings, bicycles chained up, many dark corners, smooth cobbles, not somewhere I would be glad to walk down at night, but it saved me time and I was very keen for fresh views. Up Farringdon, she text me that she was running late, that I should keep on walking up towards Clerkenwell. If I could slow down, but I could not. For a few yards I would slacken my pace, but then something caused me to resume the same speed as before, overtaking other pedestrians and dodging the incoming. Her suggestion that I move up through Farringdon and then to Clerkenwell only strengthened my desire to keep on walking forever, to not stop and meet her, to wear out soles through to my socks and not look back. There was a crossroads at which I stopped for all the crisscrossing traffic. In every direction I sensed that there was something brand new waiting to be discovered. I pulled out my phone and found where she wanted to meet; I was already there. Unusual to be early. I walked in circles, through the market, a predictable assortment of cafes, eateries, pubs and restaurants, nail salons, somewhere to buy a leather briefcase, a florist. It was ripe with affluent young white couples on pavement tables enjoying a temperate October evening. After I had committed two laps of the place, I called to see where she was, and then found her through the streets, walking towards me with a phone to her ear.

We had been talking for exactly a week. She was Italian, blonde, used to be in a metal band, worked for the British government on maritime law*, painted fish and sea creatures for fun, wrote approximately two poems a year, played Dungeons & Dragons every Tuesday evening from eight o’clock till eleven, and was romantically involved with Leonard Cohen. As soon as I saw her, I lost interest, for I could neither find her attractive—contradicting her photographs—nor feel any sort of connection or gravity toward her; nonetheless my predicament now dictated that I spend the next couple of hours with her in a fruitless exercise of politeness and affability.

She and I sat down outside a pub with all the other affluent young white couples. She does not drink, so she ordered a small ginger beer, and I ordered a pale ale. You cannot trust anyone who does not drink, I thought to myself. She told me about a friend she had lost because she called him a ‘pansy-ass bitch’, and a woman in her office who put it about, and who she had eventually called out on her bed-hopping proclivities. It was all very dull and I wanted to get drunk. She was drinking her ginger beer very slowly. She said that a person’s job defines them and was of the utmost importance; I replied, in the strongest possible terms, that I disagreed, and she looked down her nose at me. I stopped the barman walking past and asked for another pint. If I had to sit here, then I may as well drink.

My Thursday night has cancelled, she said. Could I do then, she said. ‘That’ll work,’ I said. Thursday morning I trimmed my beard and took some toiletries to work, where I passed the day in a kind of nervous excitement. Half-six, she said, in Farringdon. My reflection in the elevator mirror pressed back against me.

Rather walk than take the tube. Halfway, I was captured by a desire to keep on walking, past St Bartholomew’s hospital, along Chancery Lane, straight through Shaftesbury Avenue, passing by the millionaire townhouses then clear out the western suburbs and into the counties. It was not that I found myself unwilling to attend my engagement, but what could be finer than to walk and to carry on walking? Being in motion through nothing but my own limbs and wornout shoes! For so long I had traipsed the same old routes but here, in front of me, was a new one! People were walking one way and I was going another. I did venture down a road I had not been down before. It was a quiet road, with empty buildings, bicycles chained up, many dark corners, smooth cobbles, not somewhere I would be glad to walk down at night, but it saved me time and I was very keen for fresh views. Up Farringdon, she text me that she was running late, that I should keep on walking up towards Clerkenwell. If I could slow down, but I could not. For a few yards I would slacken my pace, but then something caused me to resume the same speed as before, overtaking other pedestrians and dodging the incoming. Her suggestion that I move up through Farringdon and then to Clerkenwell only strengthened my desire to keep on walking forever, to not stop and meet her, to wear out soles through to my socks and not look back. There was a crossroads at which I stopped for all the crisscrossing traffic. In every direction I sensed that there was something brand new waiting to be discovered. I pulled out my phone and found where she wanted to meet; I was already there. Unusual to be early. I walked in circles, through the market, a predictable assortment of cafes, eateries, pubs and restaurants, nail salons, somewhere to buy a leather briefcase, a florist. It was ripe with affluent young white couples on pavement tables enjoying a temperate October evening. After I had committed two laps of the place, I called to see where she was, and then found her through the streets, walking towards me with a phone to her ear.

We had been talking for exactly a week. She was Italian, blonde, used to be in a metal band, worked for the British government on maritime law*, painted fish and sea creatures for fun, wrote approximately two poems a year, played Dungeons & Dragons every Tuesday evening from eight o’clock till eleven, and was romantically involved with Leonard Cohen. As soon as I saw her, I lost interest, for I could neither find her attractive—contradicting her photographs—nor feel any sort of connection or gravity toward her; nonetheless my predicament now dictated that I spend the next couple of hours with her in a fruitless exercise of politeness and affability.

She and I sat down outside a pub with all the other affluent young white couples. She does not drink, so she ordered a small ginger beer, and I ordered a pale ale. You cannot trust anyone who does not drink, I thought to myself. She told me about a friend she had lost because she called him a ‘pansy-ass bitch’, and a woman in her office who put it about, and who she had eventually called out on her bed-hopping proclivities. It was all very dull and I wanted to get drunk. She was drinking her ginger beer very slowly. She said that a person’s job defines them and was of the utmost importance; I replied, in the strongest possible terms, that I disagreed, and she looked down her nose at me. I stopped the barman walking past and asked for another pint. If I had to sit here, then I may as well drink.

‘Did you

want to get something to eat?’ she asked.

‘Not really.’

‘What is it with English men and thinking that just drinking all night without eating is an acceptable date?’

‘I can’t speak for us all, but drinking is just more fun than eating. Besides there’s calories in this here,’ I said, indicating the cold pint that had just been placed before me—‘I’m no nutritionist but calories are calories.’

‘So when do you eat?’

‘If I can get away with it, I don’t.’

‘Fucking hell.’

Her accent, rather than retaining any hint of Italian, switched between American—in both volume and squawk—and posh English, both quite unpleasant to my ear. It would have been disastrous if I ordered a third pint while she was still on her small ginger beer. ‘Let’s get something to eat,’ she said, and we went around the corner to a pizza place. (The last time I had ordered from there was with H—n, twelve lifetimes ago, a much better experience as we scoffed in apartment warmth before a nature documentary. Now things were different.) We took a table in the basement. She ordered a mineral water, and I got myself another beer. She told me about her previous relationship and how heartbroken he was, how hard he was taking it, leading me to suggest she stop meeting up with him—‘This is something you don’t usually see. You keep on meeting him and it’s gone be hard for him to move on, otherwise he’s just living in hope that you’re gone get back together.’ ‘You’re right,’ she said, but I could tell from the way she said it that she would not cease their rendezvous. She divulged that she was not the sort to become infatuated with men, and then relayed, at length, a story about a German colleague she had adored and who had coldly rejected all her advances. I listened intently and told her—‘This would make an excellent short story.’†

I thought we were on our way to another bar, until she pulled out a score to settle the bill I had paid for dinner and, after an exceedingly uncomfortable hug, went up the road for her bus stop. I crossed the traffic and wracked my brain for anyone who might be at a pub on my way home, but came up short. The tube was quiet. I stood and looked around; did the mathematics in my head—from her twenty, I was up about seven quid; not a complete disaster. Neither disheartened nor disappointed, I regarded my predicament, the entire evening, with a resigned apathy. What was I searching for? What did I care? Was I simply finding ways to pass the time? I got on an intercity train and read. It felt good to be alone again. Outside of the station it was raining. A cigarette and enough cash to get me back to my parents. The cabbie looked at me tiredly, neither of us in the mood for chitchat until we came to a closed road. He began cursing in a thick Indian accent—‘For fuck’s sake! Bloody idiots!’ He said ‘bloody’ just like my grandmother used to. I directed him and we sped off down a country road, pitch black, no signs, just us and his feckless disregard for speed limits. ‘Go down here, man!’ I shouted and he did as I said. He kept on cursing—‘Those fuckin bastards! Bloody idiots! Where’re the fuckin signs?!’ ‘Don’t worry about it, geez, you’re on the meter… go down here this will bring us out just right.’ ‘But there’s no diversion signs!’ ‘Don’t worry about the diversion signs, just trust me.’ I found a great happiness in the affair, and even more joy as, passing my guitar teacher’s house from when I was fifteen, we came out exactly where I thought we would. He paused his car to shout at one of the workmen—‘Forget about it, geez, let’s go.’ And we spoke the rest of the way, closer now for having made it through our ordeal. ‘How do I get out of here?’ he asked. ‘Get down to the seafront, then go right along, keep following that road, and it’ll get you back, it’ll bring you out near the university.’ I found some use in directing him, and a joyousness in our conversation. We wished each other a good-night. I stood in the rain outside my parents’ house and smoked another cigarette. My brother was asleep in the living room. I got into bed and looked at some pornography, it stopped me from thinking, it stopped me from sleeping.

* ‘You’re a crook, Captain Hook! Judge, won’t you throw the book at the pirate…!’

† Which I hope to write someday, a tale of black forest gâteaux and heartbreak.

‘Not really.’

‘What is it with English men and thinking that just drinking all night without eating is an acceptable date?’

‘I can’t speak for us all, but drinking is just more fun than eating. Besides there’s calories in this here,’ I said, indicating the cold pint that had just been placed before me—‘I’m no nutritionist but calories are calories.’

‘So when do you eat?’

‘If I can get away with it, I don’t.’

‘Fucking hell.’

Her accent, rather than retaining any hint of Italian, switched between American—in both volume and squawk—and posh English, both quite unpleasant to my ear. It would have been disastrous if I ordered a third pint while she was still on her small ginger beer. ‘Let’s get something to eat,’ she said, and we went around the corner to a pizza place. (The last time I had ordered from there was with H—n, twelve lifetimes ago, a much better experience as we scoffed in apartment warmth before a nature documentary. Now things were different.) We took a table in the basement. She ordered a mineral water, and I got myself another beer. She told me about her previous relationship and how heartbroken he was, how hard he was taking it, leading me to suggest she stop meeting up with him—‘This is something you don’t usually see. You keep on meeting him and it’s gone be hard for him to move on, otherwise he’s just living in hope that you’re gone get back together.’ ‘You’re right,’ she said, but I could tell from the way she said it that she would not cease their rendezvous. She divulged that she was not the sort to become infatuated with men, and then relayed, at length, a story about a German colleague she had adored and who had coldly rejected all her advances. I listened intently and told her—‘This would make an excellent short story.’†

I thought we were on our way to another bar, until she pulled out a score to settle the bill I had paid for dinner and, after an exceedingly uncomfortable hug, went up the road for her bus stop. I crossed the traffic and wracked my brain for anyone who might be at a pub on my way home, but came up short. The tube was quiet. I stood and looked around; did the mathematics in my head—from her twenty, I was up about seven quid; not a complete disaster. Neither disheartened nor disappointed, I regarded my predicament, the entire evening, with a resigned apathy. What was I searching for? What did I care? Was I simply finding ways to pass the time? I got on an intercity train and read. It felt good to be alone again. Outside of the station it was raining. A cigarette and enough cash to get me back to my parents. The cabbie looked at me tiredly, neither of us in the mood for chitchat until we came to a closed road. He began cursing in a thick Indian accent—‘For fuck’s sake! Bloody idiots!’ He said ‘bloody’ just like my grandmother used to. I directed him and we sped off down a country road, pitch black, no signs, just us and his feckless disregard for speed limits. ‘Go down here, man!’ I shouted and he did as I said. He kept on cursing—‘Those fuckin bastards! Bloody idiots! Where’re the fuckin signs?!’ ‘Don’t worry about it, geez, you’re on the meter… go down here this will bring us out just right.’ ‘But there’s no diversion signs!’ ‘Don’t worry about the diversion signs, just trust me.’ I found a great happiness in the affair, and even more joy as, passing my guitar teacher’s house from when I was fifteen, we came out exactly where I thought we would. He paused his car to shout at one of the workmen—‘Forget about it, geez, let’s go.’ And we spoke the rest of the way, closer now for having made it through our ordeal. ‘How do I get out of here?’ he asked. ‘Get down to the seafront, then go right along, keep following that road, and it’ll get you back, it’ll bring you out near the university.’ I found some use in directing him, and a joyousness in our conversation. We wished each other a good-night. I stood in the rain outside my parents’ house and smoked another cigarette. My brother was asleep in the living room. I got into bed and looked at some pornography, it stopped me from thinking, it stopped me from sleeping.

* ‘You’re a crook, Captain Hook! Judge, won’t you throw the book at the pirate…!’

† Which I hope to write someday, a tale of black forest gâteaux and heartbreak.