Concerning Good Time Stingray

Turner

put down the box and pulled out his rod. He set down his tent, stool and packed

lunch in the sand. In a moment he would erect the tent and stow away everything

neatly so that he knew exactly where it was, but for a moment, pausing and

stretching his hands out from their burden, he would stare at the sea. This

would be the time, he thought. The sun had already been up for a few hours and it

was very warm for May. Down the length of the beach he could see other

fishermen, some still arriving, some well into it beneath the morning sun.

There was not a cloud in the sky and birds swirled above. In no time at all,

the day-trippers would arrive, setting up their wind-breakers and thrusting

their towels out onto the sand. He finished setting up, baited his hook and

cast out, thirty-some yards from the water’s encroaching edge. He tutted,

reeled it in—with some flotsam—then re-cast, getting it, he believed, just

right. That was where he wanted the hook, and though it might drift with the

tide, he was pleased. He rested the rod in the stand and went to his tent where

he retrieved a thermos and poured his first cup of coffee, which, despite the

weather, he wrapped his hands around.

![]()

At half-ten, Shanks walked toward him. Turner had seen him earlier two groynes away and thought to say hello but avoided it; now he could not, as Shanks trudged clumsily through the sand toward him with a discernible spring in his step. ‘All right, Turner!’

Turner smiled, nodded and turned back to the rod—‘Not bad, Shanks, not bad.’

‘Any luck today?’

‘A couple of nibbles,’ he lied—‘But nothing biting good… You?’

‘Landed a few dabs earlier, and my boy got a bass!’

‘Nice one…’

‘Any luck with that ray?’

The question struck Turner in the gut. He had expected it, but still it hurt. ‘Stingray, Shanks,’ he corrected.

‘Yeah, any luck with that stingray?’

He got up and went to his thermos, which he knew was empty, shook it and went back to his stool. ‘No, no luck yet. But I’ll get her again. I’m not worried about that!’

‘Sure. You using that washed squ—?’

‘Don’t worry what I’m using, Shanks!’

Shanks stood there, folded his arms and spun on his heels, looking left and right—‘All right, Turner, good luck, mate. Lemme know how it goes.’ The two said good-bye and Turner went back to his thermos, shook it and returned to his stool, rubbed his hands together and followed the line down to the water. A dog was behind him, sniffing the bait box. Turner went to the dog, stroked its head and ruffled its ears. ‘Nothing here, boy—’ he looked at its belly—‘Sorry, girl. Nothing here for you, girl. Get.’ The dog ran back up the beach to her owners who were calling and apologizing to Turner, who waved his hands. He drew the line in; the bait was still there. He re-cast.

At half-ten, Shanks walked toward him. Turner had seen him earlier two groynes away and thought to say hello but avoided it; now he could not, as Shanks trudged clumsily through the sand toward him with a discernible spring in his step. ‘All right, Turner!’

Turner smiled, nodded and turned back to the rod—‘Not bad, Shanks, not bad.’

‘Any luck today?’

‘A couple of nibbles,’ he lied—‘But nothing biting good… You?’

‘Landed a few dabs earlier, and my boy got a bass!’

‘Nice one…’

‘Any luck with that ray?’

The question struck Turner in the gut. He had expected it, but still it hurt. ‘Stingray, Shanks,’ he corrected.

‘Yeah, any luck with that stingray?’

He got up and went to his thermos, which he knew was empty, shook it and went back to his stool. ‘No, no luck yet. But I’ll get her again. I’m not worried about that!’

‘Sure. You using that washed squ—?’

‘Don’t worry what I’m using, Shanks!’

Shanks stood there, folded his arms and spun on his heels, looking left and right—‘All right, Turner, good luck, mate. Lemme know how it goes.’ The two said good-bye and Turner went back to his thermos, shook it and returned to his stool, rubbed his hands together and followed the line down to the water. A dog was behind him, sniffing the bait box. Turner went to the dog, stroked its head and ruffled its ears. ‘Nothing here, boy—’ he looked at its belly—‘Sorry, girl. Nothing here for you, girl. Get.’ The dog ran back up the beach to her owners who were calling and apologizing to Turner, who waved his hands. He drew the line in; the bait was still there. He re-cast.

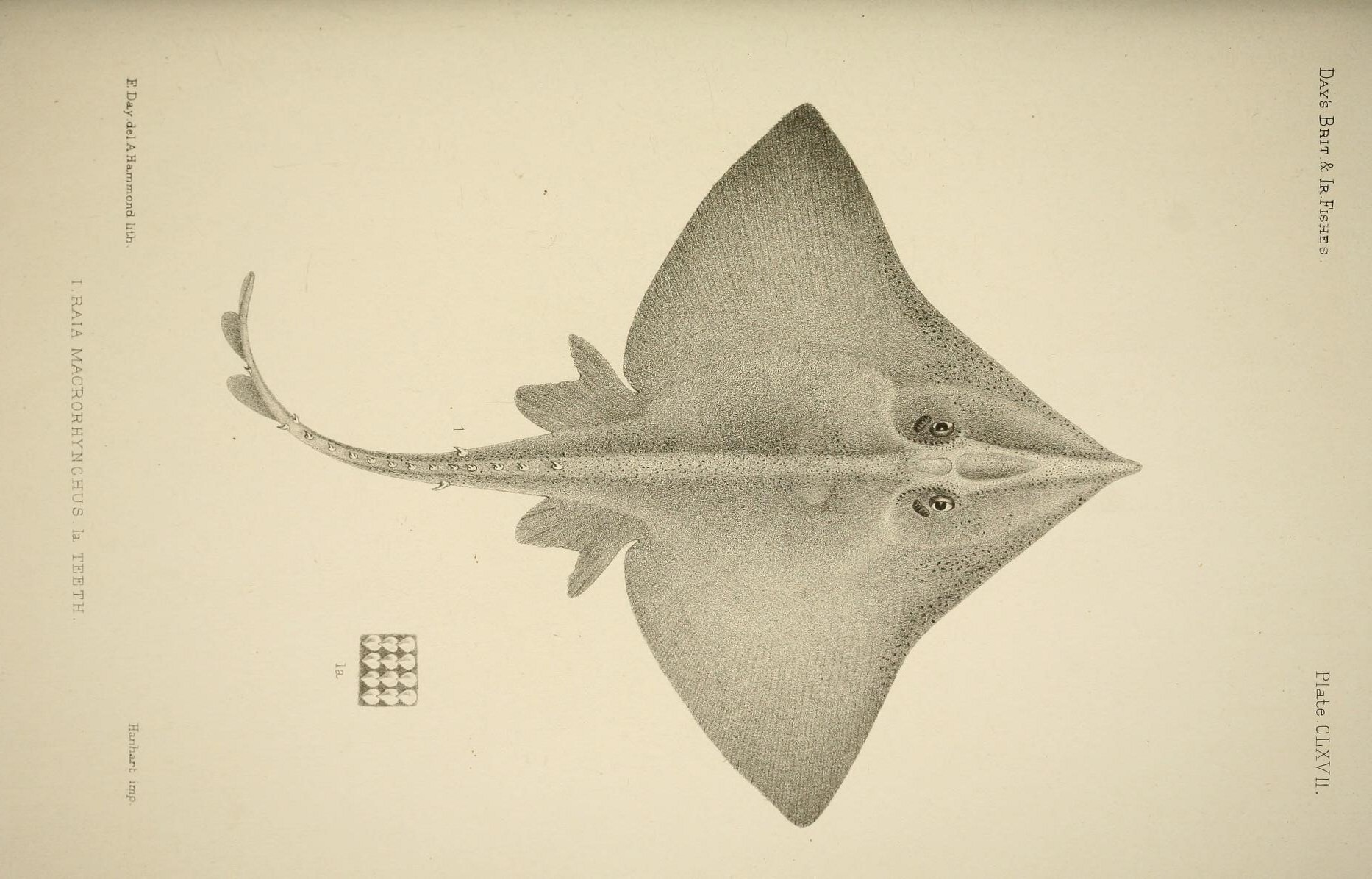

He was so happy when

he caught his first stingray. Even the day-trippers were impressed, they stood

round and gawped as Turner asked Shanks to take a photograph.

Thirty-three-pounds. Then a forty-five-pounder. The day he caught a fifty-pound

stingray he was so happy. Everyone gathered round. Shanks took the photograph

again and slapped him on the back. He told everyone about his fifty-pound

stingray, everyone and anyone who would listen. His wife tired of hearing about

the fifty-pound stingray. He got the photograph printed and framed and hung it

on the stairs. Every night, as he walked up to bed he looked at the photograph.

Then, all of a sudden, the stingray stopped biting. The water went still. He

went to the exact same spot every time, but nothing. They were definitely

there, he thought, and if they could be caught once then they could be caught

again. He used the same bait, the same rod, the same line; he cast in the exact

same spot of water. Nothing. He would keep trying. He had to catch a stingray

again. It consumed him. All week at work he could only think of getting back

down to the beach and landing that stingray again, the fifty-pounder. If not

the fifty-pounder, then a smaller stingray, even twenty-pound would be amazing.

He began to curse his own desperation. Fishing lost its joy and all he found

was torment. He saw that he was going mad but could do nothing to stop himself

from thinking of it. ‘Maybe they’ve migrated or something,’ his wife said to

him over dinner, as he prodded his food. He leapt up—‘They don’t migrate!

Stingray don’t migrate!’ How could it be that one day he could catch such a

beautiful giant fish and then the next there be nothing. Some days there might be

a tug at the line, a ripple on the surface, but nothing bit, nothing was drawn

in. It was all he could do but to sit and stare.

He snapped out of his thoughts as he sensed someone beside him; it was a young boy in swim shorts sharing his big-eyes between the sea and Turner—‘What are you doing?’ Turner told him. ‘What are stingray?’ Turner told him. ‘They’re sharks?’ Turner told him. ‘Cousins?’ Turner told him. ‘Have you caught any fish today?’ Turner told him. The boy turned and ran, kicking up sand in his wake that sprayed the side of the tent.

![]()

Three days ago, a dead whale washed up on the beach: a forty-foot fin whale. It was only a juvenile, so beautiful and perfect, its jaw reclined shut. Turner arrived early that day, eighty minutes before the police and various maritime & wildlife authorities cordoned off the beach. He never set up but just stood there with his kit, looking at the immense carcass and occasionally wiping his eyes. The whale’s ridged belly raised up to the sun and gulls scampered around the leviathan’s edges. A policemen requested he left the beach—‘No fishing today, mate, sorry.’ What if that day had been the day? He would never know. He went home and weeded the beds with his wife, feeling morose and despondent.

He snapped out of his thoughts as he sensed someone beside him; it was a young boy in swim shorts sharing his big-eyes between the sea and Turner—‘What are you doing?’ Turner told him. ‘What are stingray?’ Turner told him. ‘They’re sharks?’ Turner told him. ‘Cousins?’ Turner told him. ‘Have you caught any fish today?’ Turner told him. The boy turned and ran, kicking up sand in his wake that sprayed the side of the tent.

Three days ago, a dead whale washed up on the beach: a forty-foot fin whale. It was only a juvenile, so beautiful and perfect, its jaw reclined shut. Turner arrived early that day, eighty minutes before the police and various maritime & wildlife authorities cordoned off the beach. He never set up but just stood there with his kit, looking at the immense carcass and occasionally wiping his eyes. The whale’s ridged belly raised up to the sun and gulls scampered around the leviathan’s edges. A policemen requested he left the beach—‘No fishing today, mate, sorry.’ What if that day had been the day? He would never know. He went home and weeded the beds with his wife, feeling morose and despondent.

‘Folk are saying maybe

the whale scared the stingray away or ate them all, or something.’ Shanks was

beside him again. He wished he would go away and leave him alone. He did not

want to take his eye away from the water.

‘Seems unlikely.’ Unexpectedly, even shocked by himself as he did it, Turner offered Shanks a piece of his wife’s shortbread, which he was picking at from an unfolded piece of tinfoil. Shanks said—‘Ooh!’ and took a bit. ‘Very nice,’ he said. ‘Why don’t you come down this end with us? Swear those rocks are swarming with bass.’

Bite, thought Turner. Please bite. Just one more. Just let me land one more decent sized stingray—or any sized stingray—please. Imagine the line going, the reel spinning and rushing to take the rod! the curvature! the feel of it fighting in my grip. Digging my feet into the sand and pulling the fish toward me. It would make me so happy. I will photograph you and you will make me so happy. Give me a break. I will accept even the smallest nibble, the wobble of the line, anything. Let me know you’re still there.

At half-six he watched Shanks pack up his things and leave, waving good-bye and wishing him good luck. By quarter-to-eight, Turner was so hungry that he had to leave without a thing. The beach was empty and the sun setting, though not quite touching the horizon. Now his attention was withdrawn, everything seemed cold. With resentment and still gazing at it forlornly, he walked away from his part of the beach. For the rest of the season, he returned to that exact spot, but he never caught another stingray.

* * *

She did not take her eyes off him, and then resumed her notes. ‘Interesting,’ she said.

He thought he should clarify himself—‘I’m not comparing her to fish or stingray or whatever,’ and straight away he felt as though he’d insulted her intelligence. ‘Maybe she’s just that patch of the ocean, I dunno … I saw the fishermen on my walk and… that’s what it seemed like to me, seemed like the best way to explain it.’ They were sat opposite each other. She was still jotting down her notes; he always wanted to see what her notes said. ‘Like, the stingrays are the good times. And now they’ve gone and I never know if it’s just ‘cause they moved on or if they no longer go for it, or they got wise to it or … I dunno… maybe I was just lucky in the first place and am a shitty fisherman, really. I mean, how often can I keep going back to that place on the beach and hoping to land a stingray again?’

She did not answer his question; instead—‘No, it’s good.’

‘Like, what if I move on from that part of the beach to another? I’ll never catch that stingray again, you know? I know in that patch of beach I can catch the biggest stingray. I dunno.’ He said ‘I dunno’ a lot, thought he was babbling; although it was his money, he often felt as though he was babbling or wasting her time, not doing it right. ‘It’s dumb but I guess it’s helping me process it, or something…’ He trailed off. She kept writing.

‘So when I asked “What it is about you that makes it okay to just sit & wait?” you came up with fishermen and stingrays.’

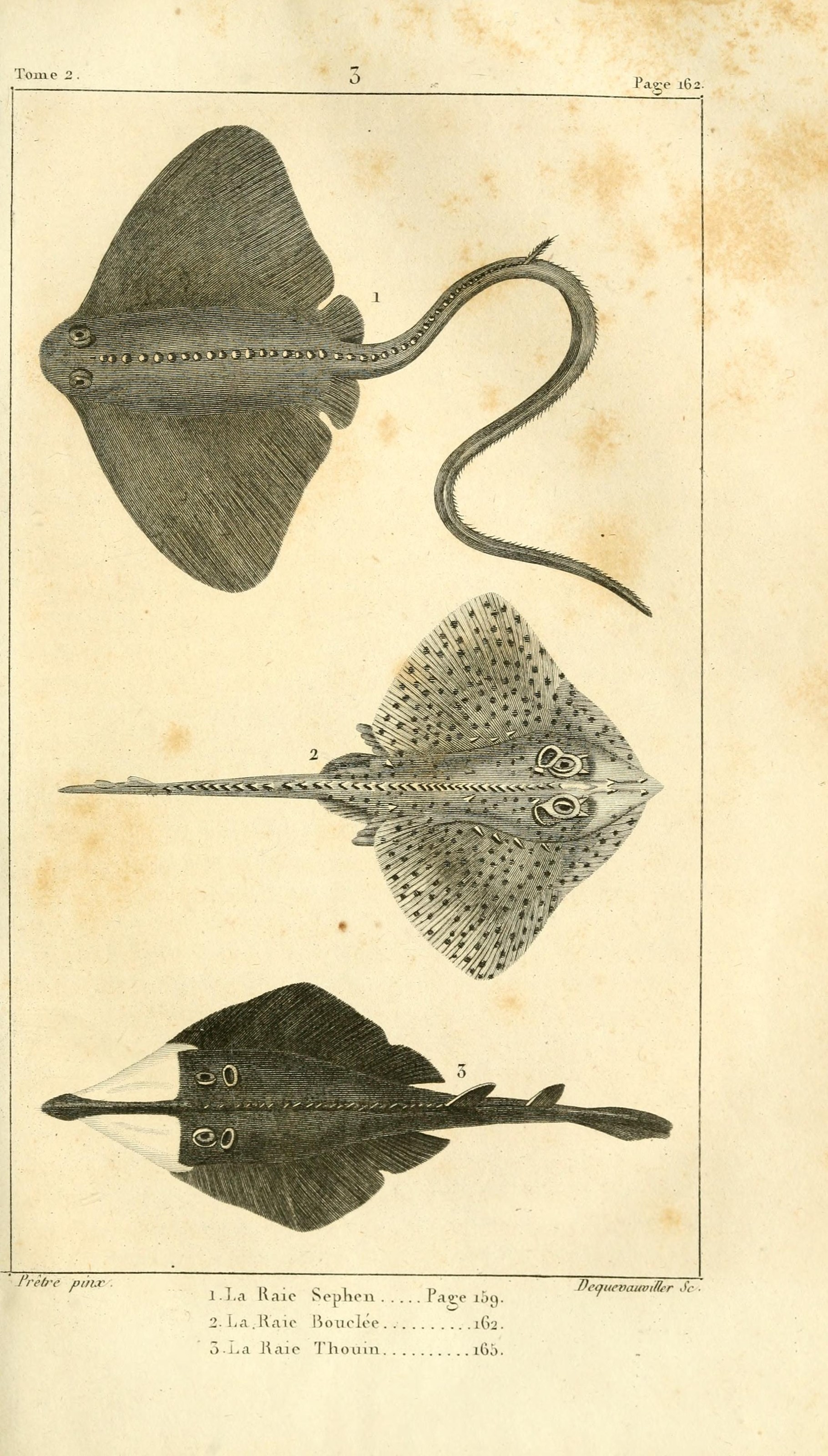

He smiled, maybe a small chuckle and she did, too. She had not really expected it, but she thought about what the beach in his mind looked like. She had seen a stingray once on a holiday many years ago in Spain when she had tried her hand at scuba diving on her husband’s birthday. The stingray did not mind her floating there several feet from the surface, gliding so close she thought she might be able to reach out and touch it. She couldn’t. It looked so smooth to the touch and the sunlight from above coursed along its body in circles that formed and broke with the waves.

‘So I guess, like I said, it’s hope and nostalgia. I dunno how something can be so good and then go to shit … And then—as you say—I’m just sitting there, waiting.’ She finished writing and relaxed her pen, folding her hands. He shook his head, looked at the eave of the window, where the blinds shuffled in the breeze. ‘Maybe she migrated,’ he said with a little laugh, wiping his eyes and clearing his throat.

‘Seems unlikely.’ Unexpectedly, even shocked by himself as he did it, Turner offered Shanks a piece of his wife’s shortbread, which he was picking at from an unfolded piece of tinfoil. Shanks said—‘Ooh!’ and took a bit. ‘Very nice,’ he said. ‘Why don’t you come down this end with us? Swear those rocks are swarming with bass.’

Bite, thought Turner. Please bite. Just one more. Just let me land one more decent sized stingray—or any sized stingray—please. Imagine the line going, the reel spinning and rushing to take the rod! the curvature! the feel of it fighting in my grip. Digging my feet into the sand and pulling the fish toward me. It would make me so happy. I will photograph you and you will make me so happy. Give me a break. I will accept even the smallest nibble, the wobble of the line, anything. Let me know you’re still there.

At half-six he watched Shanks pack up his things and leave, waving good-bye and wishing him good luck. By quarter-to-eight, Turner was so hungry that he had to leave without a thing. The beach was empty and the sun setting, though not quite touching the horizon. Now his attention was withdrawn, everything seemed cold. With resentment and still gazing at it forlornly, he walked away from his part of the beach. For the rest of the season, he returned to that exact spot, but he never caught another stingray.

* * *

She did not take her eyes off him, and then resumed her notes. ‘Interesting,’ she said.

He thought he should clarify himself—‘I’m not comparing her to fish or stingray or whatever,’ and straight away he felt as though he’d insulted her intelligence. ‘Maybe she’s just that patch of the ocean, I dunno … I saw the fishermen on my walk and… that’s what it seemed like to me, seemed like the best way to explain it.’ They were sat opposite each other. She was still jotting down her notes; he always wanted to see what her notes said. ‘Like, the stingrays are the good times. And now they’ve gone and I never know if it’s just ‘cause they moved on or if they no longer go for it, or they got wise to it or … I dunno… maybe I was just lucky in the first place and am a shitty fisherman, really. I mean, how often can I keep going back to that place on the beach and hoping to land a stingray again?’

She did not answer his question; instead—‘No, it’s good.’

‘Like, what if I move on from that part of the beach to another? I’ll never catch that stingray again, you know? I know in that patch of beach I can catch the biggest stingray. I dunno.’ He said ‘I dunno’ a lot, thought he was babbling; although it was his money, he often felt as though he was babbling or wasting her time, not doing it right. ‘It’s dumb but I guess it’s helping me process it, or something…’ He trailed off. She kept writing.

‘So when I asked “What it is about you that makes it okay to just sit & wait?” you came up with fishermen and stingrays.’

He smiled, maybe a small chuckle and she did, too. She had not really expected it, but she thought about what the beach in his mind looked like. She had seen a stingray once on a holiday many years ago in Spain when she had tried her hand at scuba diving on her husband’s birthday. The stingray did not mind her floating there several feet from the surface, gliding so close she thought she might be able to reach out and touch it. She couldn’t. It looked so smooth to the touch and the sunlight from above coursed along its body in circles that formed and broke with the waves.

‘So I guess, like I said, it’s hope and nostalgia. I dunno how something can be so good and then go to shit … And then—as you say—I’m just sitting there, waiting.’ She finished writing and relaxed her pen, folding her hands. He shook his head, looked at the eave of the window, where the blinds shuffled in the breeze. ‘Maybe she migrated,’ he said with a little laugh, wiping his eyes and clearing his throat.