But Beautiful

One’s relationship with loss is hard to articulate. It is as individual

to each of us as a our fingerprints, taste in music, or the way we might walk

from one side of the room to the other; the same muscles and organs, the same nerves

firing, the same brain and its destination, but altogether a different lurch, a

unique carriage, the way we place our feet, the sway of our hips, swinging of arms

and the minute differences in posture. The author has listened to much of the

same music as you, but trace the worn grooves of our disparate favourite

records and they will most certainly be exceptional, perhaps even in genre,

country of origin or decade. Furthermore, the teeth in your mouth and my own

are different, though they are the same in quantity, emerged from a near-identical

structure at similar ages, perform precisely the same function, they will be

different in colour, form, alignment, they will be different as every chip

comes with a story. And so, one’s relationship with loss is different.

I, the author, write here of romantic loss. It is a shade apart from mortal loss, yet not a different colour altogether. As individual as one might be, the romance between them and another human being is most definitely a fresh definition of infinity. For every distinction you define in yourself, it is adjusted, consciously or otherwise, as it revolves around another distinctive individual. Thus, every relationship is more unique than one’s self, and consequently the loss that comes to befall those who have, unwillingly, had that relationship ended is not to be taken lightly, for it has not happened to any organism or sentient being ever in the history of the universe.

It was a thought that struck the author, myself, as he was masturbating in the shower on the morning of his thirty-seventh birthday.

Much has been written before regarding my association of certain Londinium passages with particular relationships. Indeed, there are still roads, avenues, streets of my native capital that I am uncomfortable – even resistant – to walking along. Even now, a sushi chain restaurant down the back of Gresham St conjures in me intense abdominal aches, immense emotional turmoil as I recall us both squeezing sachets of wasabi onto our plates as we were falling in love but did not know it. No longer can I listen to Nashville Skyline or anything by the Shangri-Las.

After such a loss, one attempts to survive as long as it takes to recover. Paragraphs from their past, whole chapters! must be erased, scrubbed out, and anything that reminds or seeks to reinsert those paragraphs and those chapters must be turned away from. To turn away from time is surely such a waste!

At first, I did not realise what I was doing. There was a model from some grey and wetpine state in America. I thought she was beautiful, quite beautiful. She had short black hair, a slim waist, small breasts, a big bum and many tattoos of only black ink, which softened blue on her pale skin. Who can remember how I first arrived upon her photographs, but there were many of her in Pacific northwestern forests, on a motorcycle, smiling over a dish of extravagant food. There were amateur photographs of her covered in spit, shibari’d against a backdrop of magenta silk with her blackhaired pinkness split by the rope, there was a capture of the exact moment her partner – a handsome man, also tattooed – ejaculated into her mouth, also filled with individual teeth that, otherwise, perform exactly the same tasks as my own. I did not notice that I was becoming so impressed with her, that I sought to see as much of this stranger as I could on my evenings alone.

Then I realised what I was doing, and it took me by surprise so that I may have even chuckled at myself! How could I not see? This young lady on the other side of the planet reminded me of the person I had fallen in love with and then left me. Besides, her hair was exactly the same as my partner’s before they had grown theirs out, in the early days of the relationship. This stranger was a retreat back in time.

The goldfish is taken home from the fair in a plastic bag, all of it laid in the tank, so that the temperatures softly shift, and then – only then – is the bag opened and the fish introduced to the tank where it is free to flutter, to swim in its gawping existence against the glass once more.

I, the author, write here of romantic loss. It is a shade apart from mortal loss, yet not a different colour altogether. As individual as one might be, the romance between them and another human being is most definitely a fresh definition of infinity. For every distinction you define in yourself, it is adjusted, consciously or otherwise, as it revolves around another distinctive individual. Thus, every relationship is more unique than one’s self, and consequently the loss that comes to befall those who have, unwillingly, had that relationship ended is not to be taken lightly, for it has not happened to any organism or sentient being ever in the history of the universe.

It was a thought that struck the author, myself, as he was masturbating in the shower on the morning of his thirty-seventh birthday.

Much has been written before regarding my association of certain Londinium passages with particular relationships. Indeed, there are still roads, avenues, streets of my native capital that I am uncomfortable – even resistant – to walking along. Even now, a sushi chain restaurant down the back of Gresham St conjures in me intense abdominal aches, immense emotional turmoil as I recall us both squeezing sachets of wasabi onto our plates as we were falling in love but did not know it. No longer can I listen to Nashville Skyline or anything by the Shangri-Las.

After such a loss, one attempts to survive as long as it takes to recover. Paragraphs from their past, whole chapters! must be erased, scrubbed out, and anything that reminds or seeks to reinsert those paragraphs and those chapters must be turned away from. To turn away from time is surely such a waste!

At first, I did not realise what I was doing. There was a model from some grey and wetpine state in America. I thought she was beautiful, quite beautiful. She had short black hair, a slim waist, small breasts, a big bum and many tattoos of only black ink, which softened blue on her pale skin. Who can remember how I first arrived upon her photographs, but there were many of her in Pacific northwestern forests, on a motorcycle, smiling over a dish of extravagant food. There were amateur photographs of her covered in spit, shibari’d against a backdrop of magenta silk with her blackhaired pinkness split by the rope, there was a capture of the exact moment her partner – a handsome man, also tattooed – ejaculated into her mouth, also filled with individual teeth that, otherwise, perform exactly the same tasks as my own. I did not notice that I was becoming so impressed with her, that I sought to see as much of this stranger as I could on my evenings alone.

Then I realised what I was doing, and it took me by surprise so that I may have even chuckled at myself! How could I not see? This young lady on the other side of the planet reminded me of the person I had fallen in love with and then left me. Besides, her hair was exactly the same as my partner’s before they had grown theirs out, in the early days of the relationship. This stranger was a retreat back in time.

The goldfish is taken home from the fair in a plastic bag, all of it laid in the tank, so that the temperatures softly shift, and then – only then – is the bag opened and the fish introduced to the tank where it is free to flutter, to swim in its gawping existence against the glass once more.

Even the glasses she wore were like my exgirlfriend’s, because their

skulls were similar, their bone structure, and they knew what complimented. One

time, I thought to write this model, inform her of my predicament and the

relief she had provided. No, I said to myself, that would be strange. It was

already strange enough. Things would pass soon enough.

All day I was morose with heartbreak, but this model was enough for me to dip my toe into, a fix of sorts. The scent of my ex was all over the flat, was in the shower, the kitchen, ran deep into our mattress; memories scattered here and there; constantly I was tormented by the memory of their laugh; their voice rang in my mind as though it were a churchbell, persistent, historic, holy. And I returned to this American stranger. I was drunk in the evenings, to deal, to survive, and she seemed to innoculate me against the heartbreak. All day my thoughts reminded me of them, and how in love I was, but in the evenings the stranger undressed as my ex and I fucked. Much like the cheap wine I had taken to buying, it took the edge off.

The stranger disappeared halfway through my course of treatment. I assumed she broke up with her partner. After that, I moved into a new flat.

Five years later, it would happen again. The author, myself, did not notice it at first but became fixated on a photographer’s model, this time from Germany. She had a pronounced philtrum, exquisite cheekbones and jaw, long thin limbs, sagging breasts and thick labia, plump like an exclamation point. Again, I became mildly obsessed. It is too much to pen here; it is tiresome. She is not marked with the same stick-and-poke tattoos of my ex, but she stares in the same way, towards a lens reflected into an eye different from my own. It is over two years now since I first stared at the model. Still, I do not tire.

On the morning of my thirty-seventh birthday – the author’s thirty-seventh birthday – I sat on the toilet and read through all of her text messages that I had saved. Arising earlier than preferred, I went to shower before my brother and his girlfriend awoke, as they both take so long and we had an 11:10 boat to catch. Early messages were characterised by sex, and then by emotional declarations – half missing – that echoed around my consciousness as though it were a cavernous cathedral. They impact on me greatly. They are frequently painful to the gaze but in a dawn where I struggled so hard to be buoyant, I returned to her words. What led me to confront her prose on such a delicate day? Her messages were lost in time, chiselled into the cave wall of my mobile phone as though historians might picture us together on the boulevards of Tallinn or Piccadilly in centuries to come.

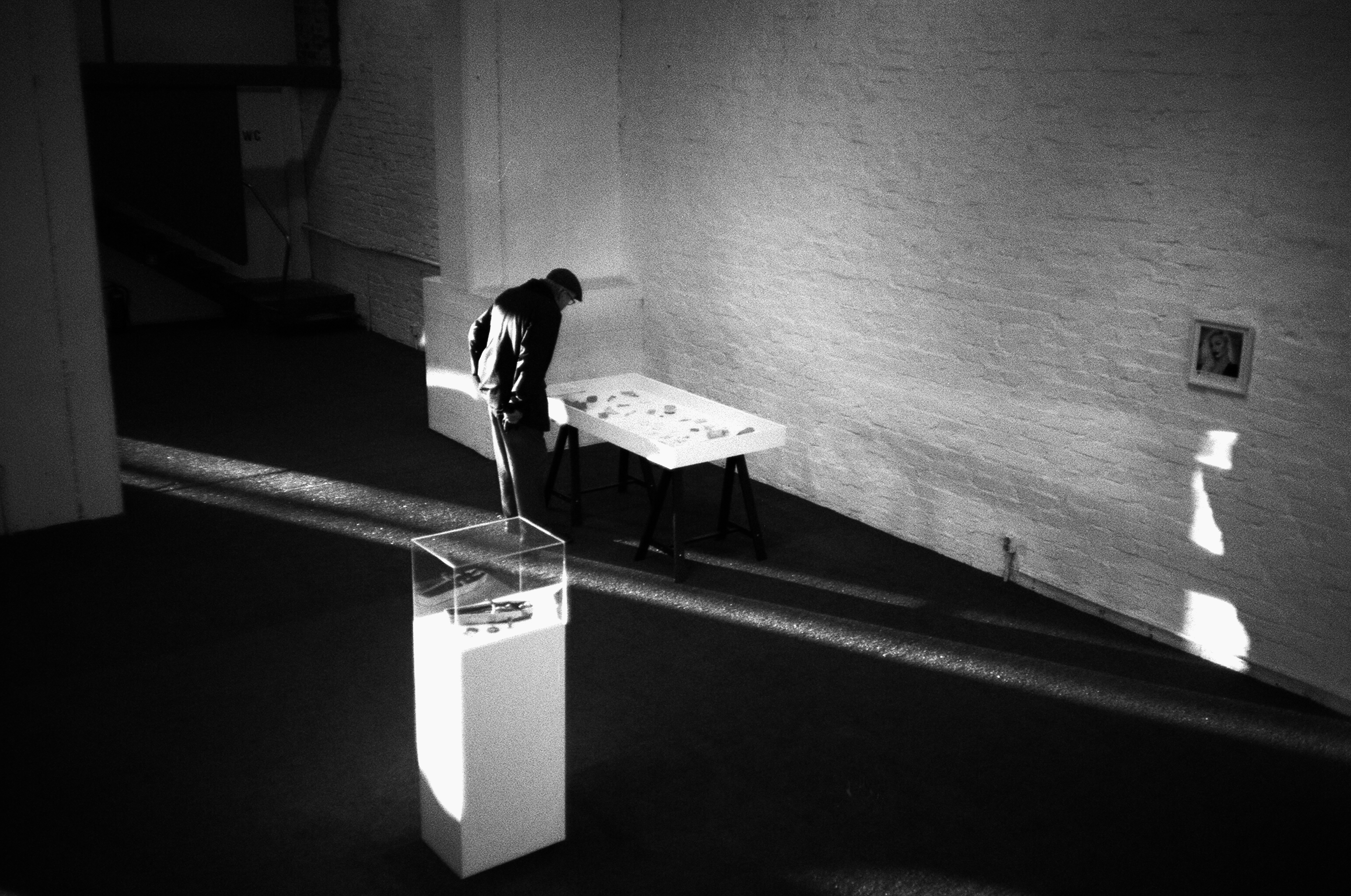

How many lyrics of pop songs do I contain within my head? Every verse, line and word in the right order, the sound of it attempted exactly; the notes, tune, the timbre, the accent and dialect. Each I recall in thought or voice. The wet cement of my mind is stroked even so with the tone of her voice, the way she chops onions, the delicacy with which she tried on necklaces in charity shops, or kissed me in the gallery. And though I may have only heard that song but once, part of it perhaps remains, a melody or phrase, it is indelible and will be recounted and repeated when I least expect it.

There is a spot in my parents’ home – between the living room and kitchen, next to the small table upon which a bouquet of flowers often perfumes – that I recall, without explanation, a song from my youth. I begin tapping the rhythm on my chest and humming the guitar before I even realise what I am doing. What is it about that small space – no more than a metre-squared – that should cause such a remembrance? I do not know. So it goes.

When I orgasm, over the course of its twenty-or-so-second bliss, I find that I am flooded with thoughts that are out of nowhere, random and occasionally off-putting. They are not usually related at all to what had brought me there. At that moment, in the shower on the thirty-seventh birthday, amongst a series of uninvited thoughts, flashes and overwhelming pictures, I then thought of a line from a song: ‘Love is funny or it’s sad,’ from But Beautiful by Billie Holiday. It is one, then it is the other; always the last.

All day I was morose with heartbreak, but this model was enough for me to dip my toe into, a fix of sorts. The scent of my ex was all over the flat, was in the shower, the kitchen, ran deep into our mattress; memories scattered here and there; constantly I was tormented by the memory of their laugh; their voice rang in my mind as though it were a churchbell, persistent, historic, holy. And I returned to this American stranger. I was drunk in the evenings, to deal, to survive, and she seemed to innoculate me against the heartbreak. All day my thoughts reminded me of them, and how in love I was, but in the evenings the stranger undressed as my ex and I fucked. Much like the cheap wine I had taken to buying, it took the edge off.

The stranger disappeared halfway through my course of treatment. I assumed she broke up with her partner. After that, I moved into a new flat.

Five years later, it would happen again. The author, myself, did not notice it at first but became fixated on a photographer’s model, this time from Germany. She had a pronounced philtrum, exquisite cheekbones and jaw, long thin limbs, sagging breasts and thick labia, plump like an exclamation point. Again, I became mildly obsessed. It is too much to pen here; it is tiresome. She is not marked with the same stick-and-poke tattoos of my ex, but she stares in the same way, towards a lens reflected into an eye different from my own. It is over two years now since I first stared at the model. Still, I do not tire.

On the morning of my thirty-seventh birthday – the author’s thirty-seventh birthday – I sat on the toilet and read through all of her text messages that I had saved. Arising earlier than preferred, I went to shower before my brother and his girlfriend awoke, as they both take so long and we had an 11:10 boat to catch. Early messages were characterised by sex, and then by emotional declarations – half missing – that echoed around my consciousness as though it were a cavernous cathedral. They impact on me greatly. They are frequently painful to the gaze but in a dawn where I struggled so hard to be buoyant, I returned to her words. What led me to confront her prose on such a delicate day? Her messages were lost in time, chiselled into the cave wall of my mobile phone as though historians might picture us together on the boulevards of Tallinn or Piccadilly in centuries to come.

How many lyrics of pop songs do I contain within my head? Every verse, line and word in the right order, the sound of it attempted exactly; the notes, tune, the timbre, the accent and dialect. Each I recall in thought or voice. The wet cement of my mind is stroked even so with the tone of her voice, the way she chops onions, the delicacy with which she tried on necklaces in charity shops, or kissed me in the gallery. And though I may have only heard that song but once, part of it perhaps remains, a melody or phrase, it is indelible and will be recounted and repeated when I least expect it.

There is a spot in my parents’ home – between the living room and kitchen, next to the small table upon which a bouquet of flowers often perfumes – that I recall, without explanation, a song from my youth. I begin tapping the rhythm on my chest and humming the guitar before I even realise what I am doing. What is it about that small space – no more than a metre-squared – that should cause such a remembrance? I do not know. So it goes.

When I orgasm, over the course of its twenty-or-so-second bliss, I find that I am flooded with thoughts that are out of nowhere, random and occasionally off-putting. They are not usually related at all to what had brought me there. At that moment, in the shower on the thirty-seventh birthday, amongst a series of uninvited thoughts, flashes and overwhelming pictures, I then thought of a line from a song: ‘Love is funny or it’s sad,’ from But Beautiful by Billie Holiday. It is one, then it is the other; always the last.