Bathroom To Bedroom To Kitchen

And when night falls, when

the last of day’s gold blues into darkness, the reflection of a room two floors

below echoes off a window opposite. There are angles in effect, angles that may

be broken down into numbers, but a triangle is formed from one living room to

the above. That is where I am perched, tremulously opening another beer, in the

subdued light of my own accommodation. Only with my lights off can the reflection

be recognised; only with my lights off can I summon the temerity to pause and

stare! The arrangement of rooms is identical, and so by passing from my

bathroom to bedroom to kitchen, I pass through their bathroom to bedroom to

kitchen. Already there, I am a ghost. If I reach out to touch them, they will

not feel my fingers but the loosest draught of cold air like ajar. This voyeurism

will be the death of me.

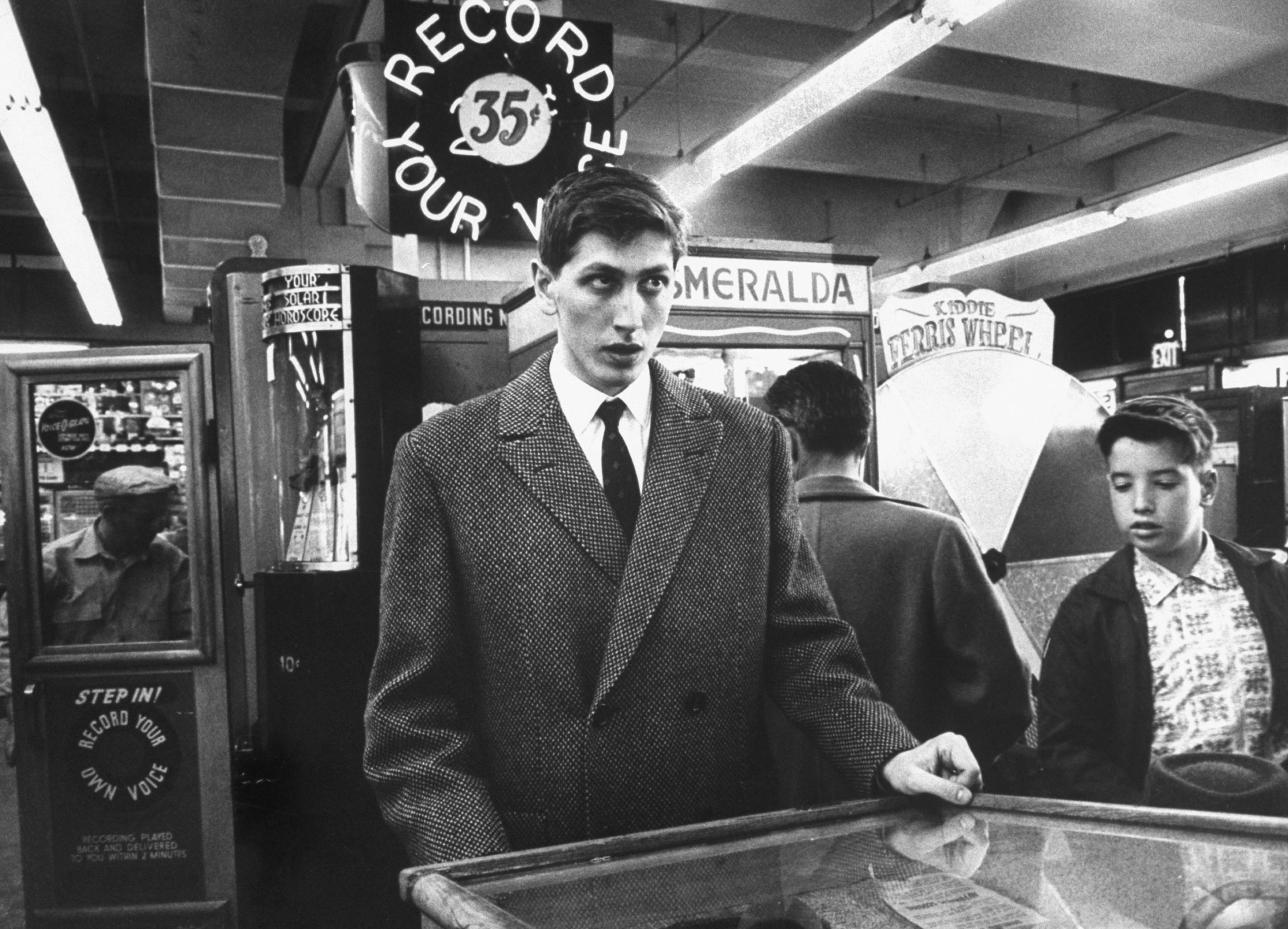

The reflection is sixties’ television, it is blurry and half-formed, bristled and tripped up in the air of its transmission. It is distinguishable only inasmuch as one must interpret it, their eyes doing all the work. The colours are faded. The outlines are dragged across one another.

She does not live alone. In a certain passage of imagination, she lived alone, although now she does not. The table, its position a shadow, is ornate with placemats, civilly arranged for dinner. The table is nearsmothered in placemats, so that little of the wood shines through. Look at them, I think. It is a scene from cinema. It is a puncture in the privacy of one person to another. No one can record this; eventually it will disappear like confetti in a churchyard.

Despite my attempts, wandering back & forth, only she is visible. The anonymous partner, he is merely a sculpted arm that tenses its fork from dish to somewhere unseen. She talks in his direction.

I am not long home. Showered and wakened, I seek to bury the worries of my mind. The evening lull, the fracas of a worrier and his troubles! Fingertips smell like last night’s chopped garlic.

She has her elbow on the table, her right hand with its glinted cutlery frozen in midair. Depicted jaggedly is her profile, bare arms, hair tied back, a plate of indeterminate food. Do not lean against the chair, quite comfortable to stand, to spectate like punters at a horserace. The shift of her jaw, the flickering of her lips convey silence. The tenses shift. She is then and now. She is a stranger plucked from the cosmos. I should turn away. The table was laid. The cutlery smeared. Dishes half-full.

Eating is not on my mind. It will be hours before I do.

The reflection is sixties’ television, it is blurry and half-formed, bristled and tripped up in the air of its transmission. It is distinguishable only inasmuch as one must interpret it, their eyes doing all the work. The colours are faded. The outlines are dragged across one another.

She does not live alone. In a certain passage of imagination, she lived alone, although now she does not. The table, its position a shadow, is ornate with placemats, civilly arranged for dinner. The table is nearsmothered in placemats, so that little of the wood shines through. Look at them, I think. It is a scene from cinema. It is a puncture in the privacy of one person to another. No one can record this; eventually it will disappear like confetti in a churchyard.

Despite my attempts, wandering back & forth, only she is visible. The anonymous partner, he is merely a sculpted arm that tenses its fork from dish to somewhere unseen. She talks in his direction.

I am not long home. Showered and wakened, I seek to bury the worries of my mind. The evening lull, the fracas of a worrier and his troubles! Fingertips smell like last night’s chopped garlic.

She has her elbow on the table, her right hand with its glinted cutlery frozen in midair. Depicted jaggedly is her profile, bare arms, hair tied back, a plate of indeterminate food. Do not lean against the chair, quite comfortable to stand, to spectate like punters at a horserace. The shift of her jaw, the flickering of her lips convey silence. The tenses shift. She is then and now. She is a stranger plucked from the cosmos. I should turn away. The table was laid. The cutlery smeared. Dishes half-full.

Eating is not on my mind. It will be hours before I do.

When I have had my fill –

because often I return, go back, sneak another peek, the reticence of peeping –

I give them a few hours, and note, with relish, the kitchen light extinguished,

a hidden sofa burdened. The lamps burn orange; the television set blue no

matter what is on, piercing electric blooms all over the furniture, shifting

and uncertain. It is not long, by eleven o’clock, that the apartment is doused

in darkness and there is nothing to see. Who knows where they have gone? I

pinch myself. The play is ended. The curtain descended. I stand up from my seat

and walk away.

Snow falls this spring. Still the disease catches people. Should I be afraid? I am one of few still wearing a mask. Hah, you cannot catch me! It brings a tremendous amount of comfort that my face should be hidden. A new mask every morning like a glass of juice, like an allergy tablet, like a shower and tied shoelaces. Often the mask becomes so hot that I feel faint, and yet I keep it on! The expulsions of my throat are regurgitated and swallowed like cud. If I should find myself in the daze of exhaustion, then I will hold Sontag’s Against Interpretation to my nose and fight it, until I can no longer and sleep, sweet sleep, until—I fling the book up in the air, convulsing. My sleepy consciousness juggles the book in the air, swiping hands, bouncing it from left to right and up again. The man next to me, deep in a game on his mobile phone, flinches away from my madness. The book lands on me, lands on the seat, lands on him, falls to the floor. ‘Sorry, geez,’ I say and bend down with a grunt to pick it up. And I am hot with embarrassment under my mask.

The clocks bring darker mornings, but—‘Don’t worry’ sing the gulls, ‘It will not last.’ How many times our planet has tossed and turned about the same routine, its shoulders leaning here & there, how many times we have celebrated the glimmer of a new season! The rabbi welcomed us at a wooden door, greeting cordially the schoolchildren flooding past him, their legs excited out the coach, teeth stung with twohour sugar, midday London just so crisp and cool. This wind was not there then.

It penetrates my collar. Tuck the chin down, keep the liver’s warmth around the lungs.

There is a perceived sense of isolation. Hours of therapy and thousands spent to reveal to her that, despite evidence to the contrary, I consider myself alone, remote, in a tower of stone. I am not, she assures me, and points, as though she were a shepherd along a worn path. But, most certainly, I am alone while needing to reassure myself out the neurosis. It is not such a bother, no more than a rounded pebble in the shoe.

And so I stare, as night falls, as day’s glorious gold kind of tatters itself into moribund blue, into the distorted reflection of a life two floors down and as far away as Earendel. I do not weep, for my bones are adjusting into the bask of slowly. When their lights have gone, as their stillness lingers, I put myself to the window, to the cold of ultimate earth, and the radiators swamp heat about me; I know, for certain as dawn, they are curled in bed together like cochlea.

Snow falls this spring. Still the disease catches people. Should I be afraid? I am one of few still wearing a mask. Hah, you cannot catch me! It brings a tremendous amount of comfort that my face should be hidden. A new mask every morning like a glass of juice, like an allergy tablet, like a shower and tied shoelaces. Often the mask becomes so hot that I feel faint, and yet I keep it on! The expulsions of my throat are regurgitated and swallowed like cud. If I should find myself in the daze of exhaustion, then I will hold Sontag’s Against Interpretation to my nose and fight it, until I can no longer and sleep, sweet sleep, until—I fling the book up in the air, convulsing. My sleepy consciousness juggles the book in the air, swiping hands, bouncing it from left to right and up again. The man next to me, deep in a game on his mobile phone, flinches away from my madness. The book lands on me, lands on the seat, lands on him, falls to the floor. ‘Sorry, geez,’ I say and bend down with a grunt to pick it up. And I am hot with embarrassment under my mask.

The clocks bring darker mornings, but—‘Don’t worry’ sing the gulls, ‘It will not last.’ How many times our planet has tossed and turned about the same routine, its shoulders leaning here & there, how many times we have celebrated the glimmer of a new season! The rabbi welcomed us at a wooden door, greeting cordially the schoolchildren flooding past him, their legs excited out the coach, teeth stung with twohour sugar, midday London just so crisp and cool. This wind was not there then.

It penetrates my collar. Tuck the chin down, keep the liver’s warmth around the lungs.

There is a perceived sense of isolation. Hours of therapy and thousands spent to reveal to her that, despite evidence to the contrary, I consider myself alone, remote, in a tower of stone. I am not, she assures me, and points, as though she were a shepherd along a worn path. But, most certainly, I am alone while needing to reassure myself out the neurosis. It is not such a bother, no more than a rounded pebble in the shoe.

And so I stare, as night falls, as day’s glorious gold kind of tatters itself into moribund blue, into the distorted reflection of a life two floors down and as far away as Earendel. I do not weep, for my bones are adjusting into the bask of slowly. When their lights have gone, as their stillness lingers, I put myself to the window, to the cold of ultimate earth, and the radiators swamp heat about me; I know, for certain as dawn, they are curled in bed together like cochlea.