£932.61

One day it

will sink in, but not tonight. It occurred to me, as I swept the top of the

wardrobe with a wet rag, that the dust I rolled into black lines could well

have been there since moving-in-day, could have landed from the fifteenth of July

air, two-thousand-and-fifteen. And what dust? a piece of my skin, or some exhaust

from the street below? It was sunny back then, the middle of summer, but now it

is late-November, and I have wrinkles round my finite eyes, greys on the

temple. The moving-in was grander than the moving-out. I remember, when the boxes

were stacked to permit a path through the room, we uncorked a bottle of champagne

and toasted; there was no champagne anymore. On this occasion there was only a

gradual reduction in the studio contents, as I carried out bag after bag to the

bins outside or the car, the burning odour of bleach, the hurry and vacancy. To

say good-bye to the filled & decorated room would have been an ache, but by

the time we were finished, there was nothing left to say good-bye to: the

landlord’s shelves were empty of all my books; where I stood and played guitar,

make-believing it was a stage, was desolate; the table where I had spilled coffee

and played videogames was unrecognisable; the bed was loveless, no longer

stained with blood or sweat; the walls where art & photographs had hung

were white again; the desk upon which I had tapped haiku, meaningless prose and

oiled nudes appeared smaller, less like a platform, less like anything, squeezed

into the small corner of a small room. I never realised I could take dust for

granted.

After I moved in, I invited friends over for a kind of gathering, or party, on a Friday evening in August. They bought booze at the cornershop that I had already become known in, making a row, and we became very drunk and everyone had fun! It was the first party I had thrown, and it was a gay affair with dancing and singing. That studio flat became for me a reprieve from the heartbreak of my failed relationship; there was nothing to remind me of Lisa, no bed where we had lain, or furniture scratched by our cats; I faltered away from the home we had made for ourselves, away from the windowsill where Tim & Pippa would lay and look out. It was a chance to begin again, as they say, and it was unhaunted. Time is a healer, but no-one ever said how much time. The landlord was a large man who probably worked the door in his younger days, smoked Silk Cutand took an instant liking to me; he swallowed every room he walked into and kept a loyal circle of Muslim brothers around him, doing the maintenance, gas, electric, minor repairs, decorating.

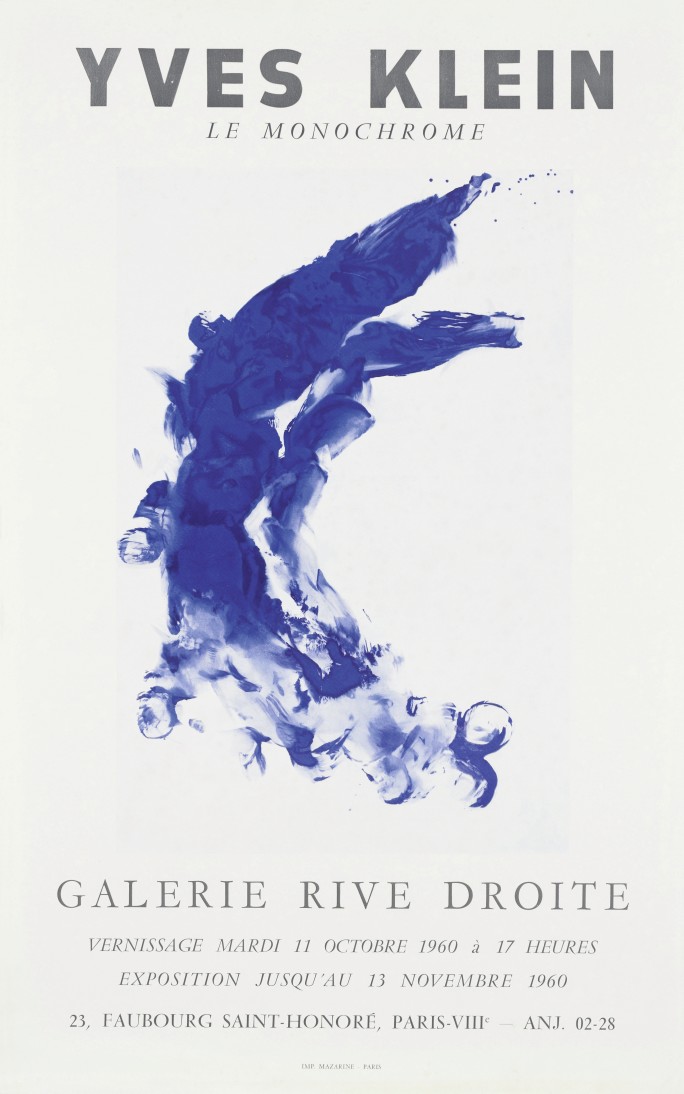

In the evenings, I turned up the music loud and leaned out the window, looking down on the street below, drunk, smoking and happy to be alive. Plants breathed life into me, fairy lights too. A large print of Yves Klein’s Anthropométries hung above the sofa. The neighbourhood seemed different, even then. Slowly, I got back into single life with a 15-watt amplifier and I looked out to the skyline where I wondered how my city was doing.

Charlotte came along, the first person with any sway to intrude, but pleasantly, upon my flat, with her big thighs and electric laugh. She always appeared to be covered in my cum, every time she woke up she told me not to read the news, and I rolled over. I picture her next to the water of St Katherine with a collar round her throat, but I was unaccustomed to the love she showed me, the love I was so lucky to receive, and I fled! Then Simon and I arose to watch Bob Ross over cafetieres, harking back to university until we rolled to Docklands for lunch in the green cement and glass.

When the attacks happened on London Bridge, I watched from my window, saw the helicopters hovering and lights flashing. Pausing my film, I got up and stared listening as the news came in. The night sky was blinking and everything was hushed but for the rushing sound of emergency services.

I watched roadmen fighting in the streets, dogs attack dogs, I watched the homeless shoot up and heard windows smashing. The view outside of my window in the evenings was my cinema. At weekends, I would leave and wander around the city alone, then return and amuse myself as though I were the last person on earth; just me and that room. It seems like two lifetimes ago, but back then I lived next-door to a trumpeter, who rehearsed at seven in the morning, and, really, I had no problem with that because the sound of a trumpet goes great with a springtime morning. As summer approached, they practiced the wedding march, and when one day I heard them playing the Star Wars theme, I began punching the air and drunkenly shouting—‘Fuckin get in! Yes mate!’ and banging the wall, cheering. One day the trumpeter was there, and then they were gone. I missed them, I miss them.

After I moved in, I invited friends over for a kind of gathering, or party, on a Friday evening in August. They bought booze at the cornershop that I had already become known in, making a row, and we became very drunk and everyone had fun! It was the first party I had thrown, and it was a gay affair with dancing and singing. That studio flat became for me a reprieve from the heartbreak of my failed relationship; there was nothing to remind me of Lisa, no bed where we had lain, or furniture scratched by our cats; I faltered away from the home we had made for ourselves, away from the windowsill where Tim & Pippa would lay and look out. It was a chance to begin again, as they say, and it was unhaunted. Time is a healer, but no-one ever said how much time. The landlord was a large man who probably worked the door in his younger days, smoked Silk Cutand took an instant liking to me; he swallowed every room he walked into and kept a loyal circle of Muslim brothers around him, doing the maintenance, gas, electric, minor repairs, decorating.

In the evenings, I turned up the music loud and leaned out the window, looking down on the street below, drunk, smoking and happy to be alive. Plants breathed life into me, fairy lights too. A large print of Yves Klein’s Anthropométries hung above the sofa. The neighbourhood seemed different, even then. Slowly, I got back into single life with a 15-watt amplifier and I looked out to the skyline where I wondered how my city was doing.

Charlotte came along, the first person with any sway to intrude, but pleasantly, upon my flat, with her big thighs and electric laugh. She always appeared to be covered in my cum, every time she woke up she told me not to read the news, and I rolled over. I picture her next to the water of St Katherine with a collar round her throat, but I was unaccustomed to the love she showed me, the love I was so lucky to receive, and I fled! Then Simon and I arose to watch Bob Ross over cafetieres, harking back to university until we rolled to Docklands for lunch in the green cement and glass.

When the attacks happened on London Bridge, I watched from my window, saw the helicopters hovering and lights flashing. Pausing my film, I got up and stared listening as the news came in. The night sky was blinking and everything was hushed but for the rushing sound of emergency services.

I watched roadmen fighting in the streets, dogs attack dogs, I watched the homeless shoot up and heard windows smashing. The view outside of my window in the evenings was my cinema. At weekends, I would leave and wander around the city alone, then return and amuse myself as though I were the last person on earth; just me and that room. It seems like two lifetimes ago, but back then I lived next-door to a trumpeter, who rehearsed at seven in the morning, and, really, I had no problem with that because the sound of a trumpet goes great with a springtime morning. As summer approached, they practiced the wedding march, and when one day I heard them playing the Star Wars theme, I began punching the air and drunkenly shouting—‘Fuckin get in! Yes mate!’ and banging the wall, cheering. One day the trumpeter was there, and then they were gone. I missed them, I miss them.

I always

listened to the building around me, to gauge who else lived there, or, when it

seemed so quiet, whether I was truly alone. I only really said hello to the

young Muslim family on my floor – who moved out after my second year – and a

Chinese family and their nanny on the floor below; those were the faces I saw

most often. There was a woman who smoked outside a lot and I watched her until

a chance meeting one inebriated night when I turned halfway up the stairs and

said—‘You’re that woman who smokes outside, aren’t you?’ She moved out not long

after. Aaron stayed on his twenty-seventh birthday. We ran around town until

late and caught a cab back to mine and I sang In The Closet the

entire way home as he highly laughed. Cardboard pizza and American Pie,

four hours sleep, contact lens glued to the eyes, and back to work.

Then came Alex, who peeled away my distance over the course of an afternoon in an Indonesian restaurant. We went back, fucked and played video games, putting each other off and laughing. Laughter soundtracking every pleasant memory. Who was this stranger that I had exposed myself to, and, look at her! so kindly stroking my head and I not wishing to be a burden. She led me all over East London, and I followed in the August heat, we kissed in the middle of the road before she went on her business trips to New York and Paris. ‘The walls are too thin at mine,’ she said as she masturbated down the phone to me, spread next to an open window and I heard the police cars pass by underneath her wet thighs. I remember how quiet everything was when she slammed shut my front door.

As I took out a bag of rubbish, I looked down upon the steadiness my feet trod and saw that, o! they had tarmac’d over the cobblestones of the road! Buried, how horrid! Those cobbles were always so beautiful as I looked down, especially the way they caught the sun and shone like scales of this city’s reptile, and then, without regard, they had been covered by the smoothest and most grotesque of surfaces. The road markings had been laid down perfectly like white Hollywood teeth. As I had done many times before, I lifted the bag into the big tin bin. It rang like a bell. There was the wheelchair outside of the ground-floor-flat opposite, a flat I had observed for many hours as they did the school run or rushed back from Mosque or hurried to karate class, as they celebrated Eid underneath a pagoda in the car park, as they waved away their visiting families, I watched them play frisbee or football and they always made me smile. I fell in love with them so much that I must write them a letter about it.

Finally, there was Her, and She chased me out of the apartment. Finally, there was Her. Finally, She was the exit music, and every box I moved out of there had Her within it. My home – this studio flat I had lived in for over four years – no longer felt like home unless She was in it. None had settled there like She did, as though I could only smile when She dropped crumbs on the bed! She left notes upon the coffee table when She went, and I wept. She left notes underneath my pillow when She left, and I slept. Her mementos on every surface. My twelve-hundred-a-month was a purgatory until I saw Her again. And then a pandemic and then the end, and then the heartbreak as She is in another man’s flat. Mine no longer felt like my own. It was time for me to go.

As my mother urinated before our journey back, I took a photograph on my phone of the emptiness, twisted in moonlight and the lamp from my hallway, holding the door open with my heel. In the distance, entering with the letting agent, that indeterminate feeling one gets for such things as buildings, forests, people, especially people, and eventually their history, triggering a pulse through the arteries that cannot be described other than to say that if existence were filled with such things it would be a wonderful life indeed! We loaded up the car and took off. ‘Are you sad?’ Many of the shops or restaurants had changed names or closed. My parents complained about the graffiti and I cried for the graffiti. There are no words nor sentences for me and that part of town. I cried for all of it, like waving farewell. My belongings and furniture were stacked up around me in the automobile, obscuring and encasing me from the other passengers. As we got onto the motorway, the glow of the city in the rearview mirror, I glazed over; my music loud; I could smell myself, sweat from all the heavy lifting; I could smell the dust of five-and-a-half years that I had on me and the archaeology of moving from my home. The slip road angled itself as it rose from the carriageway, inertia pulling, the view changing and, outside, the clear night.

Then came Alex, who peeled away my distance over the course of an afternoon in an Indonesian restaurant. We went back, fucked and played video games, putting each other off and laughing. Laughter soundtracking every pleasant memory. Who was this stranger that I had exposed myself to, and, look at her! so kindly stroking my head and I not wishing to be a burden. She led me all over East London, and I followed in the August heat, we kissed in the middle of the road before she went on her business trips to New York and Paris. ‘The walls are too thin at mine,’ she said as she masturbated down the phone to me, spread next to an open window and I heard the police cars pass by underneath her wet thighs. I remember how quiet everything was when she slammed shut my front door.

As I took out a bag of rubbish, I looked down upon the steadiness my feet trod and saw that, o! they had tarmac’d over the cobblestones of the road! Buried, how horrid! Those cobbles were always so beautiful as I looked down, especially the way they caught the sun and shone like scales of this city’s reptile, and then, without regard, they had been covered by the smoothest and most grotesque of surfaces. The road markings had been laid down perfectly like white Hollywood teeth. As I had done many times before, I lifted the bag into the big tin bin. It rang like a bell. There was the wheelchair outside of the ground-floor-flat opposite, a flat I had observed for many hours as they did the school run or rushed back from Mosque or hurried to karate class, as they celebrated Eid underneath a pagoda in the car park, as they waved away their visiting families, I watched them play frisbee or football and they always made me smile. I fell in love with them so much that I must write them a letter about it.

Finally, there was Her, and She chased me out of the apartment. Finally, there was Her. Finally, She was the exit music, and every box I moved out of there had Her within it. My home – this studio flat I had lived in for over four years – no longer felt like home unless She was in it. None had settled there like She did, as though I could only smile when She dropped crumbs on the bed! She left notes upon the coffee table when She went, and I wept. She left notes underneath my pillow when She left, and I slept. Her mementos on every surface. My twelve-hundred-a-month was a purgatory until I saw Her again. And then a pandemic and then the end, and then the heartbreak as She is in another man’s flat. Mine no longer felt like my own. It was time for me to go.

As my mother urinated before our journey back, I took a photograph on my phone of the emptiness, twisted in moonlight and the lamp from my hallway, holding the door open with my heel. In the distance, entering with the letting agent, that indeterminate feeling one gets for such things as buildings, forests, people, especially people, and eventually their history, triggering a pulse through the arteries that cannot be described other than to say that if existence were filled with such things it would be a wonderful life indeed! We loaded up the car and took off. ‘Are you sad?’ Many of the shops or restaurants had changed names or closed. My parents complained about the graffiti and I cried for the graffiti. There are no words nor sentences for me and that part of town. I cried for all of it, like waving farewell. My belongings and furniture were stacked up around me in the automobile, obscuring and encasing me from the other passengers. As we got onto the motorway, the glow of the city in the rearview mirror, I glazed over; my music loud; I could smell myself, sweat from all the heavy lifting; I could smell the dust of five-and-a-half years that I had on me and the archaeology of moving from my home. The slip road angled itself as it rose from the carriageway, inertia pulling, the view changing and, outside, the clear night.